African Stream produced this video report: “The United States Africa Command—or AFRICOM—was founded in 2007. But it’s failed to bring peace and security. Major failures in Somalia, Libya and elsewhere have left many Africans suspecting it exists only to serve U.S. interests.”

Related Articles

Related Articles

Kenyan Women Speak Out About Kafala Exploitation in Gulf States

KIENI, Kenya—After traversing rivers, hills, valleys, sharp bends, and swaths of uncultivated land in the drier parts of central Kenya, this reporter arrived in early November to hear Anne Nyambura’s story of abuse at the hands of a Saudi employer.

Nyambura is a 53-year-old mother of five. In 2018, she traveled to Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia, with the promise of being able to send money back home with what she would earn as a domestic worker. But unable to withstand the working conditions, she breached the contract after a year.

“I was allowed to eat for only five minutes, given a lot of work and paid peanuts, contrary on what we had agreed on the contract,” the former domestic worker said. In Saudi Arabia, Nyambura expected to take home $800 per month. Instead, she received $170, or less than 25 percent of the agreed-upon amount. Meanwhile, the same role in Kenya would have earned her $150 each month. And, so, she returned to her homeland emaciated and poorer than before.

“It was a waste of time,” said Nyambura, who is among 100,000 Kenyans who have traveled to the Gulf countries to work, but whose dreams of earning to support their families have placed them in dangerous circumstances.

‘Biting Poverty’ Feeds Kafala System

Now back in the Kieni constituency in Kenya’s Nyeri County, Nyambura told Toward Freedom she had nowhere to report the dispute with her Saudi employer because the decades-old Kafala system was at work.

Gulf Cooperation Council states, such as Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, as well as the Arab states of Jordan and Lebanon have abided by the Kafala system to regulate the relationships of migrant workers with employers (“kafeels”), according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). It has been in place since the 1950s. That is when countries that had experienced a construction boom after discovering oil under their feet needed skilled laborers that they could not find among their lesser educated populations. However, migrant workers have for years aired complaints about the system. “Often the kafeel exerts further control over the migrant worker by confiscating their passport and travel documents, despite legislation in some destination countries that declares this practice illegal,” the ILO states in a policy brief.

Nyambura told Toward Freedom her employer did exactly that, plus took hold of her identification card and mobile phone, among other items.

“The issue of documents being confiscated by the employers is under Saudi Arabian law and we cannot be blamed for that,” said Mwalimu Mwaguzo, a chairperson of the Pwani Welfare Association (PWA), an alliance of 20 private recruitment agencies based in the coastal city of Mombasa. “The Kafala system that people are complaining about was introduced with the Saudi Arabian government to curb running away of domestic workers from their employer and we, as agents, have no authority to eliminate the system.”

But that is not all, according to Nyambura.

“The employer was everything and you, as a worker, have nowhere to take him in case of assault,” she told Toward Freedom, lamenting that sometimes she would get slaps and blows from the employer and that she was denied food for a couple of days.

“Biting poverty fueled by lack of opportunities is compelling many Kenyan women to travel to Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries to search for greener pastures, but reaching there many regret,” she said in a low, angry tone. “Returning home becomes an added burden.”

Making matters worse, at least 89 Kenyans—most of whom were domestic workers—died in Saudi Arabia between 2020 and 2021, according to Kenyan Foreign Affairs Principal Secretary Macharia Kamau. Their bodies were returned to Kenya or buried as unknown persons in Gulf countries. Plus, organs had been removed from some of the bodies, Kamau reported.

Mwaguzo told Toward Freedom detainees in Saudi deportation centers are either on the run from their employer or are involved in prostitution.

Remittances Flow to Kenya

According to the ILO, the migration and employment system implemented by most countries in the Arab states region is based on a relatively liberal entry policy, restricted rights, and a limited duration of employment contracts and visas.

Kafeels are liable for the conduct and safety of the migrant they bring into the country, and they can exert control over a migrant’s movement and employment.

The ILO Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR), which is responsible for evaluating the application of international labor standards, has noted “the kafala system may be conducive to the exaction of forced labor and has requested that the governments concerned protect migrant workers from abusive practices.”

Meanwhile, Amnesty International has said the situation in Qatar had worsened as it prepared to host the 2022 World Cup using migrant labor.

According to an article published by Global Policy Journal, the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) estimates more than 2.1 million workers in the Gulf from around the world are at risk of exploitation and work under inhumane conditions. In the past, some countries had halted deployment of domestic workers to Saudi Arabia. Such bans improved working conditions, increased salaries and lessened mistreatment.

If the governments of Kenya and other countries halted to deploy their workers in the Gulf, could things change?

Migration to the Gulf continues providing thousands of job opportunities and billions of dollars in remittances. Around $124 billion was remitted in 2017 from countries that adhere to Kafala. Statistics from Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) show remittances from Saudi Arabia have more than doubled in the last two years to Ksh 22.65 billion ($179 million). That amount was sent back home in the first eight months of this year, ranking the Gulf nation as the third-largest source of remittances for Kenya behind the United Kingdom and the United States. However, 2021 remittances marked the fastest growth, with a 144 percent climb since 2020.

Reports of Rape and Torture

As the country continues enjoying remittances from the Gulf, Haki Africa, a human-rights organization headquartered in Mombasa, estimates more than 200,000 Kenyans in Saudi Arabia are working in different companies and homes, and that most are working under inhumane conditions. The organization’s estimate is double that of the Kenyan’s government’s.

Haki Africa Executive Director Hussein Khalid said the Kenyan embassy in Saudi Arabia has been ignoring complaints, fueling the vice.

Khalid said most of the Kenyan women in Saudi Arabia have undergone sexual assault, physical abuse and mental torture. He said, this year alone, the organization has received 51 complaints from domestic workers in Saudi Arabia.

“We would like to urge the government of Kenya to speed up the rescue process for our women who are suffering in Gulf countries and return them home,” Khalid said. “It is the responsibility of any government to ensure that all of its citizens are safe regardless where they are.”

Joy Simiyu, a former domestic worker from Bungoma in rural western Kenya, said her Gulf-based agent declined to speak with her when she needed help. Simiyu’s employer in Saudi Arabia only allowed her to sleep four hours and eat one meal per day. Plus, the terms of the contract weren’t being abided. “[After] reaching Riyadh, I was forced to work for the relatives of the employer.”

She said one day her employer attempted to kill her, but she was able to run away and report the matter to the nearest police station. Then she was then taken to an accommodation center, a location the Saudi government runs to keep migrants before they are deported or while they are looking for work after fleeing another employer.

Now based in Nairobi, the 24-year-old revealed the accommodation center was insecure, as she learned potential employers who visited the site would sexually assault women using the promise of a job. Food, water and electricity were unavailable, too, she said.

“I would like to urge my fellow Kenyans not to go to Saudi Arabia to look for jobs, things are not good there, you better suffer in your country than in other people’s country,” she said with tears rolling down her face. “What is in Saudi Arabia is slavery and not job opportunities.”

Recruitment Agencies: ‘Mother of All Problems’

In July 2021, when appearing before the Labor and Social Welfare Committee, then-Labor Cabinet Secretary Simon Chelugui reported 1,908 distress calls from the Gulf between 2019 and 2021.

While in the Gulf, Nyambura observed governments taking action when workers from different countries contacted them about mistreatment.

“Kenyans in the Gulf are like orphans,” Nyambura said. “They have no one to protect them.

However, the Kenyan government lately appears to be taking action. A few weeks ago, Cabinet Secretary for Foreign and Diaspora Affairs Dr. Alfred Mutua traveled to Riyadh to discuss the domestic-worker issue with Saudi officials. Mutua said the two agreed Kenyan domestic-worker agencies could set up offices in Saudi Arabia to deal with issues concerning their clients. The two countries announced they are collaborating to “flush out” illegal agencies and those that break the law.

“We have to break the cartels and streamline the agencies, some of which are owned by prominent Kenyans,” Mutua told the media. He added his ministry will release a set of new instructions and procedures prospective migrant workers will be required to adhere to and meet before they can be cleared to travel to the Gulf states. The foreign ministry reported hundreds of Kenyans have been repatriated. Mutua and his Saudi counterpart agreed to the formation of a hotline (+96 6500755060) that Kenyan workers can call to report abuse.

Meanwhile, in February, the Qatari government shut down 12 recruitment agencies. The operation came a few days after Central Organization of Trade Union (COTU) Secretary General Francis Atwoli and Qatar Labor Minister Ali Marri held talks in Doha. It is part of a campaign Atwoli is involved in that also has been putting pressure on the governments of Kenya and Saudi Arabia.

Atwoli told Toward Freedom recruitment agencies must be prohibited, calling them the “mother of all problems” facing workers.

“The issue of negotiations on the terms and conditions of workers should be government to government, and not [on] the recruitment agencies,” he told Toward Freedom.

Meanwhile, recruitment agencies oppose the ban of agencies. For instance, Maimuna Hassan of Nairobi-based Asali Commercial Agencies said many people do not talk about the benefits of working through recruitment agencies. Haki Africa Rapid Response Officer Mathias Sipeta urged those aspiring to travel to the Gulf through recruitment agencies to verify them before signing agreements.

Nyambura said Atwoli has been trying to fight for workers’ rights in the Gulf, but that he gets sidetracked by Kenyan politics. She also said he lacks support from the government.

Like Simiyu, Nyambura has concluded it is better to work in Kenya. She pointed to the country’s coffee and tea farms as better options. But seeing for the first time in Kenyan history both a government official and a labor leader holding meetings with Gulf state officials has indicated to some, like Nyambura, that the situation may improve.

“Maybe under the new administration,” the former domestic worker said, “things will change.”

Shadrack Omuka is a freelance journalist based in Kenya. He writes about human rights, climate change, business and education, among other topics. His work has appeared in several publications around the world, such as Equal Times, Financial Mail, New Internationalist, Earth Island and The Continent, among others.

Egypt’s Repressive Regime Is Enabled by United States and Allies

Editor’s Note: This video report originally appeared in Peoples Dispatch.

In the aftermath of COP27, the annual global climate-change conference that took place in Egypt’s resort town of Sharm el Sheikh, Rania Khalek of BreakThrough News spoke to Peoples Dispatch about how the United States, its European allies and Israel enable the Egyptian government’s repression. She explained the role Egypt plays as a U.S. proxy in the region as well as its role in various conflicts, including the siege of Gaza.

Frantz Fanon Lives! 60 Years After His Death, Fanon’s Ideas Remain the Weapons of the Oppressed

Editor’s Note: The following is the writer’s analysis.

“The master’s room was wide open. The master’s room was brilliantly lit, and the master was there, very calm… and our people stopped dead… it was the master… I went in. “It’s you,” he said, very calm. It was I, even I, and I told him so, the good slave, the faithful slave, the slave of slaves, and suddenly his eyes were like two cockroaches, frightened in the rainy season… I struck, and the blood spurted; that is the only baptism that I remember today.” —Aimé Césaire

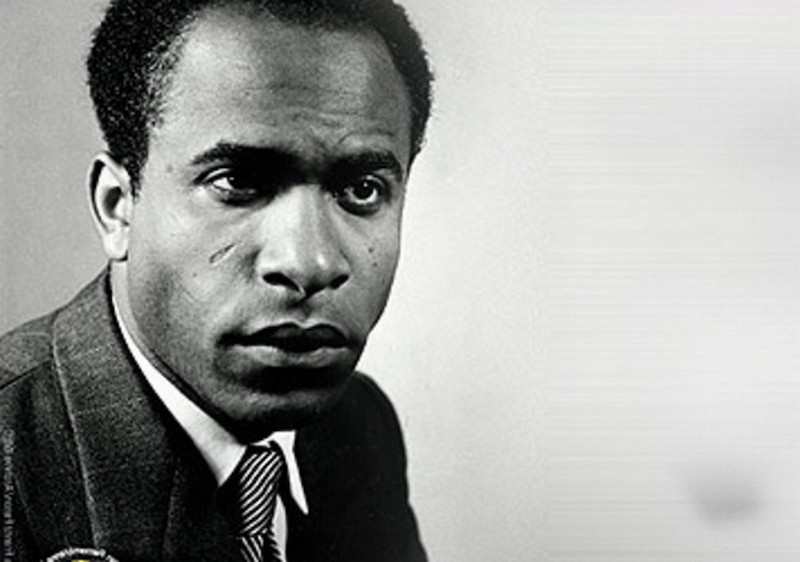

Today marks the 60th anniversary of the passing of one of the greatest thinkers to have emerged from the ranks of the oppressed, Frantz Fanon (1925-1961).

Fanon’s contributions are timeless. As long as white supremacy and neocolonialism remain in the driver’s seat of human relations, Fanon’s thought will continue to arm the colonized in the Battle of Ideas.

The Radicalization of Fanon

Born and raised in what is still France’s Caribbean island colony of Martinique, Fanon was exposed to and shaped by the everyday class and race relations that characterized the island in the early 20th century. Forced to join a segregated column of Black troops, he fought in World War II. Upon continuing his studies in post-war France, he came face to face with the racism that dominates the European world. In his first book, Black Skin, White Masks (1952), Fanon reflects on coming of age in a world, where, “For the black man there is only one destiny. And it is white.” At the time of publication, Fanon had just turned 27.

In 1953, the Martiniquais psychiatrist was assigned to Algeria, where he treated patients who were severely traumatized by the violence French colonialism had spun into motion. He met Dr. Pierre Chaulet, a French doctor who secretly treated members of the guerrilla resistance, Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), who had survived torture and captivity. “Viscerally close to his patients whom he regarded as primarily victims of the system he was fighting,” Fanon immediately became a cadre of the Algerian Revolution.1

By 1956, Fanon’s consciousness no longer allowed him to oversee operations at Blida Hospital in Algeria. In an influential resignation letter that moved many on the left, he wrote:

“There comes a time when silence becomes dishonesty. The ruling intentions of personal existence are not in accord with the permanent assaults on the most commonplace values. For many months my conscience has been the seat of unpardonable debates. And the conclusion is the determination not to despair of man, in other words, of myself. The decision I have reached is that I cannot continue to bear a responsibility at no matter what cost, on the false pretext that there is nothing else to be done.”

The Wretched of the Earth

Fanon produced a prodigious amount of intellectual work. Toward the African Revolution is a compilation of his writings on forging African and Third World unity with the Algerian Revolution at the vanguard of this process.2 A Dying Colonialism explores how the Algerian people threw off their internalized inferiority complex by turning away from the colonizer’s cultural practices and embracing their own traditions.3

He dedicated his last days to dictating the final ideas of his most moving work to his wife, Josie. Six decades after it first hit the streets of Paris, The Wretched of the Earth: The Handbook for the Black Revolution That Is Changing the Shape of the World is as accurate and explosive as ever. The title comes from the line “Arise, ye wretched of the earth” from “The Internationale,” the Second Communist International’s official anthem, and from Haitian communist intellectual Jacques Romain’s poem, “Sales négres:”

too late it will be too late

on the cotton plantations of Louisiana

in the sugar cane fields of the Antilles

to halt the harvest of vengeance

of the negroes

the niggers

the filthy negroes

it will be too late I tell you

for even the tom-toms will have learned the language

of the Internationale

for we will have chosen our day

day of the filthy negroes

filthy Indians

filthy Hindus

filthy Indo-Chinese

filthy Arabs

filthy Malays

filthy Jews

filthy proletarians.

And here we are arisen

All the wretched of the earth

all the upholders of justice

marching to attack your barracks

your banks

like a forest of funeral torches

to be done

once

and

for

all

with this world

of negroes

niggers

filthy negroes.4

How many revolutionaries the world over became enraptured in his eloquent portrayal of the “Manichaean” differences between the neighborhoods of the rich white colonizer in Algiers and the casbah (ghettoes) of the colonized?

Here within this classic, that all revolutionaries have a duty to study, reside some of the most poignant prose on how the oppressed internalize violence and project it onto themselves:

“Where individuals are concerned, a positive negation of common sense is evident. While the settler or the policeman has the right the livelong day to strike the native, to insult him and to make him crawl to them, you will see the native reaching for his knife at the slightest hostile or aggressive glance cast on him by another native, for the last resort of the native is to defend his personality vis-a-vis his brother.”

Based on his treatment of patients in the Blida Hospital, which today bears his name, Fanon’s final chapter, “Colonial War and Mental Disorders,” examines the “ineffaceable wounds that the colonialist onslaught has inflicted on our people.”5

The fundamental pillar of the book, however, was Fanon’s conviction that the colonized could only shed their fear and shame through a baptism of revolutionary violence. Fanon’s former high school teacher and mentor, Aimé Césaire, had a profound influence on him. Césaire’s words cited at the beginning of this article from his epic poem on slave liberation, “And the Dogs were Silent,” set the tone for the Fanonian worldview. Despite a chorus of liberal complaints from the West that Fanon was “too violent,” Fanon concluded:

“As you and your fellow men are cut down like dogs, there is no other solution but to use every means available to reestablish your weight as a human being.”

‘You Can Kill a Revolutionary, But You Can Never Kill the Revolution’

Though Fanon died of leukemia when he was only 36, revolutionaries the world over have picked up his fallen weapons, his ideas, and applied them to their own particular national liberation struggles. Fanon’s observations and thesis continue to mold the thinking of awakening generations in life-and-death struggles from Johannesburg to Gaza to Harlem.

As political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal writes, the Black Panthers were Fanonists. His audio essay and tribute to Fanon discuss what the psychiatrist’s anti-colonial perspicacity meant to a 15-year-old Mumia, who has spent 40 years in prison. In Seize the Time, Bobby Seale talks about the influence of Fanon on the young Panthers and how Huey P. Newton read the book seven times.6

Malcolm X, Ernesto “Che” Guevara and Nelson Mandela all traveled to independent Algeria, which emerged as an epicenter of Pan-Africanism and internationalism. Paulo Freire stated that he had to rewrite Pedagogy of the Oppressed after reading The Wretched of the Earth. Hamza Hamouchene, president of the London-based Algerian Solidarity Campaign, discusses in CounterPunch what he deems Fanon’s unique contributions to understanding nationalism, the national bourgeoisie, political education and universalism, among other themes.

It is important to highlight that Fanon was more than just a doctor and writer.

At his graveside, Vice-president of the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA) Krim Belkacem emphasized Fanon’s diverse roles in the FLN’s total war. Beginning in 1954, Fanon worked as a writer, editor and propagandist for FLN periodicals Résistance algérienne and El Moudjahid. He also was a researcher; lecturer; a FLN representative in Ghana, Ethiopia, Mali, Guinea and Congo; as well as a clandestine militant.

Looking at the work of Karl Marx, Steve Biko, Cedric Robinson, Sylvia Wynter and other examples of revolutionaries/intellectuals, the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research wrote a tribute to Fanon because of how he embodied the praxis of a radical or organic intellectual: “The world will only be shaped by the most valuable insights of philosophical striving when philosophy itself becomes worldly via participation in struggle.”

Fanon survived an assassination attempt, exile in Tunis and was staring down a crippling disease that he refused to talk about but that ultimately claimed his life. Aware he was dying, he pledged, “I will not cease my activities while Algeria still continues the struggle and I will go on with my task until my dying day.”7

Today, it is more necessary than ever to study Fanon to understand the psychological, emotional and spiritual damage wrought by neo-colonialism on the peoples of Africa, the Americas, Asia and what the Black Panthers referred to as the United States’ internal colonies. Fanon’s conclusion in The Wretched of the Earth on African and human liberation begs the same questions six decades later:

“Let us waste no time in sterile litanies and nauseating mimicry. Leave this Europe [U.S.A.] where they are never done talking of Man, yet murder men everywhere they find them, at the corner of everyone of their own streets, in all the corners of the globe.”

Danny Shaw is a professor of Caribbean and Latin American Studies at the City University of New York. He frequently travels within the Americas region. A Senior Research Fellow at the Center on Hemispheric Affairs, Danny is fluent in Haitian Kreyol, Spanish, Portuguese and Cape Verdean Kriolu.

Notes

1 Fanon, Frantz. Toward the African Revolution. New York: Grove Press. 1964.

2 Fanon, Frantz. Toward the African Revolution. New York: Grove Press. 1964.

3 Fanon, Frantz. A Dying Colonialism. New York: Grove Press. 1965.

4 Macey, David. Frantz Fanon: A Biography. London and New York: Verso. 2012.

5 Macey, David. Frantz Fanon: A Biography. London and New York: Verso. 2012.

6 Seale, Bobby. Seize the Time: The Story of The Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton. Random House: 1970.

7 Macey, David. Frantz Fanon: A Biography. London and New York: Verso. 2012.