Editor’s Note: This African Stream video report contains disturbing content.

Related Articles

Related Articles

The Geopolitics Behind Spiraling Gas and Electricity Prices in Europe

Editor’s Note: The following represents the writer’s analysis and was produced in partnership by Newsclick and Globetrotter.

The current crisis of spiraling gas prices in Europe, coupled with a cold snap in the region, highlights the fact that the transition to green energy in any part of the world is not going to be easy. The high gas prices in Europe also bring to the forefront the complexity involved in transitioning to clean energy sources: that energy is not simply about choosing the right technology, and that transitioning to green energy has economic and geopolitical dimensions that need to be taken into consideration as well.

Gas wars in Europe are very much a part of the larger geostrategic battle being waged by the United States using the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and Ukraine. The problem the United States and the EU have is that shifting the EU’s energy dependence on Russia will have huge costs for the EU, which is being missed in the current standoff between Russia and NATO. A break with Russia at this point over Ukraine will have huge consequences for the EU’s attempt to transition to cleaner energy sources.

The European Union has made its problem of a green transition worse by choosing a completely market-based approach toward gas pricing. The blackouts witnessed by people in Texas in February 2021 as a result of freezing temperatures made it apparent that such market-driven policies fail during vagaries of weather, pushing gas prices to levels where the poor may have to simply turn off their heating. In winter, gas prices tend to skyrocket in the European Union, as they did in 2020 and again in 2021.

For India and its electricity grid, one lesson from this European experience is clear. Markets do not solve the problem of energy pricing, as they require planning, long-term investments and stability in pricing. The electricity sector will face disastrous consequences if it is handed over to private electricity companies, as is being proposed in India. This is what the move to separate wires from the electricity they carry aims to achieve through Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government’s proposed amendment to the existing Electricity Act of 2003.

In order to understand the issues related to transitioning toward green energy, it is important to take a closer look at the current gas supply-related issues being faced by the European Union. The EU has chosen gas as its choice of fuel for electricity production, as it goes off coal and nuclear while also investing heavily in wind and solar. The argument advanced in favor of this choice is that gas would provide the EU with a transitional fuel for its low carbon emission path, as gas tends to produce less emissions than coal. It is another matter that gas is at best a short-term solution, as it still emits half as much greenhouse gas as coal.

As I have written earlier, the problem with green energy is that it requires a much larger capacity addition to handle seasonal and daily fluctuations that planners have not accounted for while advocating for switching over to clean energy sources. During winter, days are shorter in higher latitudes, and the world therefore gets fewer hours of sunlight. This seasonal problem with solar energy has been compounded in Europe with low winds in 2021 reducing the electricity output of windmills.

The European Union has banked heavily on gas to meet its short- and medium-term goals of cutting down greenhouse emissions. Gas can be stored to meet short-term and seasonal needs, and gas production can even be increased easily from gas fields with requisite pumping capacity. All this, however, requires advance planning and investment in surplus capacity building to meet the requirements of daily or seasonal fluctuations.

Unfortunately, the EU is a strong believer that markets magically solve all problems. It has moved away from long-term price contracts for gas and toward spot and short-term contracts—unlike China, India and Japan, which all have long-term contracts indexed to their oil prices.

Why does the gas price affect the price of electricity in the EU? After all, natural gas accounts only for about 20 percent of the EU’s electricity generation. Unfortunately for the people in the EU region, not only the gas market but also the electricity market has been “liberalized” under the market reforms in the EU. The energy mix in the grid is determined by energy market auctions, in which private electricity producers bid their prices and the quantity they will supply to the electricity grid. These bids are accepted, in order from lowest to highest, until the next day’s predicted demand is fully met. The last bidder’s price then becomes the price for all producers. In the language of Milton Friedman’s followers—who were known as the Chicago Boys—this price offered by the last bidder is its “marginal price” discovered through the market auction of electricity and, therefore, is the “natural” price of electricity. For readers who might have followed the recently concluded elections in Chile, Augusto Pinochet—who was a military dictator in Chile from 1973 to 1990—introduced the Constitution of 1980 in Chile and had incorporated the above principle in a constitutional guarantee to the neoliberal reforms in the electricity sector in the country. Hopefully, the victory of the left in the presidential elections in Chile and the earlier referendum on rewriting the Chilean constitution will also address this issue. Interestingly, it was not the former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher—as is commonly thought—who started the electricity “reforms” but Pinochet’s bloody regime in Chile.

At present in the EU, natural gas is the marginal producer, and that is why the price of gas also determines the price of electricity in Europe. This explains the almost 200 percent rise in electricity price in Europe in 2020. In 2021, according to an October 2021 report by the European Commission, “Gas prices are increasing globally, but more significantly in net importer regional markets like Asia and the EU. So far in 2021, prices tripled in [the] EU and more than doubled in Asia while only doubling in the U.S.” [emphasis added].

The coupling of the gas and the electricity markets by using the marginal price as the price of all producers means that if gas spot prices triple as has been seen recently, so will the electricity prices. No prizes for guessing who gets hit the hardest with such increases. Though there has been criticism from various quarters regarding the use of marginal price as the price of electricity for all suppliers irrespective of their respective costs, the neoliberal belief in the gods of the market has ruled supreme in Europe.

Russia has long-term contracts as well as short-term contracts to supply gas to EU countries. Putin has mocked the EU’s fascination with spot prices and gas prices and said that Russia is willing to supply more gas via long-term contracts to the region. Meanwhile, in October 2021, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said that Russia was not doing its part in helping Europe tide over the gas crisis, according to an article in the Economist. The article stated, however, that according to analysts, Russia’s “big continental customers have recently confirmed that it is meeting its contractual obligations,” adding that “[t]here is little hard evidence that Russia is a big factor in Europe’s current gas crisis.”

The question here is that the EU either believes in the efficiency of the markets or it doesn’t. The EU cannot argue markets are best when spot prices are low in summer, and lose that belief in winter, asking Russia to supply more in order to “control” the market price. And if markets indeed are best, why not help the market by expediting the regulatory clearances for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which will ship Russian gas to Germany?

This brings us to the knotty question of the EU and Russia. The current Ukraine crisis that is roiling the relationship between the EU and Russia is closely linked to gas as well. Pipelines from Russia through Ukraine and Poland, along with the undersea Nord Stream 1, currently supply the bulk of Russian gas to the EU. Russia also has additional capacity via the newly commissioned Nord Stream 2 to supply more gas to Europe if it receives the financial regulatory clearance.

There is little doubt that Nord Stream 2 is caught not simply in regulatory issues but also in the geopolitics of gas in Europe. The United States pressured Germany not to allow Nord Stream 2 to be commissioned, and also threatened to impose sanctions on companies involved with the pipeline project. Before stepping down as the chancellor of Germany in September 2021, Angela Merkel, however, resisted pressure from Washington to halt the work on the pipeline and forced the United States to concede to a “compromise deal.” The Ukraine crisis has created further pressure on Germany to postpone Nord Stream 2 even if it means worsening its twin crises of gas and electricity prices.

The net gainer in all of this is the United States, which will get the EU as a buyer for its more expensive fracking gas. Russia currently supplies about 40 percent of the EU’s gas. If this stalls, the United States, which supplies about 5 percent of the EU’s gas demand (according to 2020 figures), could be a big gainer. The United States’ interest in sanctioning Russian gas supply and not allowing the commissioning of Nord Stream 2 has as much to do with its support to Ukraine as seeing that Russia does not become too important to the EU.

Nord Stream 2 could help form a common pan-European market and a larger Eurasian consolidation. Just as it did in East and Southeast Asia, the United States has a vested interest in stopping trade following geography instead of politics. Interestingly, gas pipelines from the Soviet Union to Western Europe were built during the Cold War as geography and trade got priority over Cold War politics.

The United States wants to focus on NATO and the Indo-Pacific region, as its focus is on the oceans. In geographical terms, the oceans are not separate but a continuous body covering more than 70 percent of the world’s surface with three major islands: Eurasia, Africa and the Americas. (Although in the formulation of British geographer Halford Mackinder, the originator of the world island idea, Africa was seen as a part of Eurasia.) Eurasia alone is by far the bigger island, with 70 percent of the world’s population. That is why the United States does not want such a consolidation.

The world is passing through perhaps the greatest transition that human civilization has known in meeting the current challenges posed by climate change. To address these challenges, an energy transition is required that cannot be achieved through markets that prioritize immediate profits over long-term societal gains. If gas is indeed the transitional fuel, at least for Europe, it needs long-term policies of integrating its gas grid with gas fields, which have adequate storage. And Europe needs to stop playing games with its energy and the world’s climate future for the benefit of the United States.

For India, the lessons are clear. Markets do not work for infrastructure. Long-term planning with state leadership is what India needs to ensure supply of electricity to all Indians and ensure the country’s green transition—instead of dependence on electricity markets created artificially by a few regulators framing rules to favor the private monopoly of electricity companies.

Prabir Purkayastha is the founding editor of Newsclick.in, a digital media platform. He is an activist for science and the free software movement.

Sinking Cities Project: ‘Alexandria: Layers of History, Levels of Threat’

Editor’s Note: This article, originally published by Unbias the News, is part of the Sinking Cities Project, which covers six cities’ responses to sea-level rise. The investigation was developed with the support of Journalismfund.eu, European Cultural Foundation and the German Postcode Lottery.

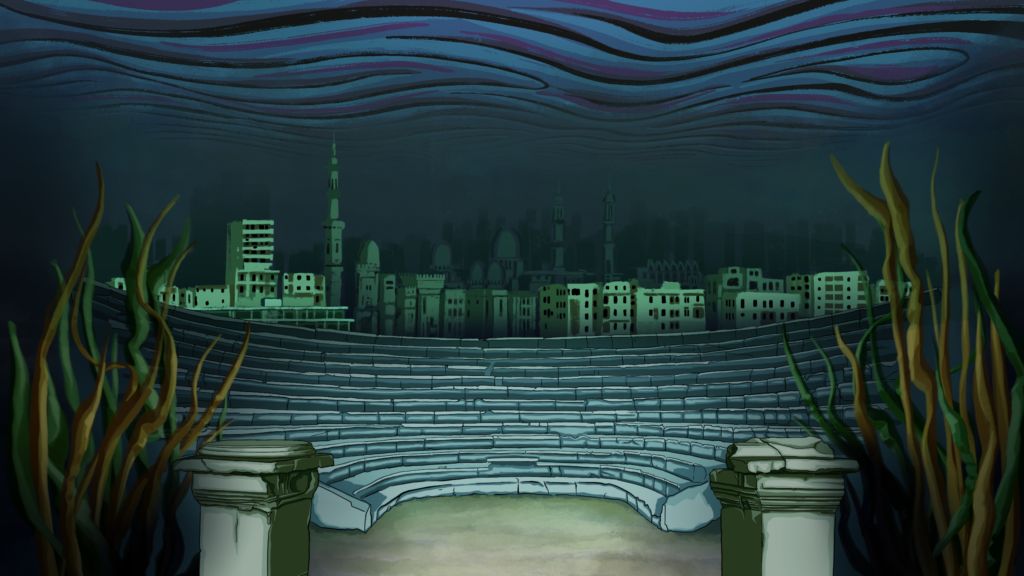

In order to visit Alexandria’s most famous museum, you need to dive into its sea. Much of this ancient Egyptian city was lost to sea, and sank beneath the waves of the Mediterranean around the 3rd or 2nd century.

Located 2.5 kilometers (1.55 miles) off the coast of Alexandria, “Abu Qir Sunken Cities Museum” hosts the underwater ruins of both the Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus cities, where visitors can see the lighthouse that was one of the world’s Seven Wonders, along with anchors, gold coins, and the remains of the palace where Cleopatra and Anthony lived their last days, all lying at the bottom of the sea, as a testament of how vulnerable humans are to nature’s forces.

Since the discovery of the two long-lost cities and other underwater sites, scientists and researchers have been striving to unravel the reason behind the collapse and submergence of these great cities more than 1,500 years ago. They are also investigating the probability of history repeating itself.

Historical Precedent

Franck Goddio, the French underwater archaeologist who, in 2000, discovered the city of Thonis-Heracleion said that parts of the city’s ancient coastline sank beneath the sea “due to a combination of natural phenomena, including a series of earthquakes and tidal waves.”

Spending most of his long career studying ancient Alexandria, Magdy Torab, professor of Geomorphology at the Faculty of Arts, Damanhour University, suggests the same reasons for what happened there. “Alexandria is located close to some active tectonic plates, we witness a lot of earthquakes from near and distant sources that caused damages to the city, both in historical and recent times. One of the effects of those land movements is causing land subsidence,” he said.

In a study published by the Austrian Academy of Sciences Press in 2018, Torab also investigated sea level variation at Alexandria over the last millennia. “There is an abrupt relative sea level rise that occurred from the mid-8th century to the end of 9th century that explains the wide movement of sinking that happened at this time.”

Exploring the different reasons that led to the disappearance of this coastal city has a special importance as it is used by scientists to predict earthquake hazards in the coastal areas today.

Torab describes the effect of the seismic activities that the ancient city of Alexandria faced at this time, “land may have subsided as a result of an earthquake that followed an undersea earthquake or tsunamis.”

Land subsidence is a gradual or sudden sinking of the earth’s surface. The phenomenon can be caused by many reasons. Some of them might be related to human activities or part of a natural process like earthquakes.

The Mediterranean region has a witnessed many destructive earthquakes, among them the 365 Crete earthquake, which happened between the fourth and sixth centuries and was followed by a devastating tsunami that swept out Alexandria, and the Nile Delta, killing thousands.

So the great port that hosted the legendary Alexandria library flooded by a giant wall of water that puts big parts of the city under the water. Does this indicate that this might happen again?

According to the UNESCO, Alexandria is among five cities in the Mediterranean sea that is under the threat and need to be “tsunami-ready” by 2030. “Statistics show that the probability of a tsunami wave exceeding 1 meter in the Mediterranean in the next 30 years is close to 100 percent.”

Between the Sky and the Sea

Ziad Morsy knows Alexandria by heart. That’s hardly surprising, considerings he and his ancestors have lived in the city for decades. But what is remarkable is how much he knows about the invisible part of Alexandria, the part settling underwater.

For more than 12 years, Morsy’s work was under the water, as a scholar at Alexandria Centre for Maritime Archaeology and Underwater Cultural Heritage, then a visiting Lecturer of Maritime Archaeology. His job was to dive in the sea and collect data, because, as he said, “to be prepared for the future we need to understand the past”.

“Global warming will definitely affect Alexandria’s shoreline. But is it going to be the reason behind its sinking? I don’t think so. From my point of view, there is a long list of reasons, and global warming comes at the end of this list,” Morsy told Unbias the News.

He summarized the factors that determine “whether Alexandria is going to stay above the water or sink under the water” in three points: The city land level, the Mediterranean sea level, and Lake Mariout.

Geographical Precarity

If you search for Alexandria in the map, you will notice the port’s unique location, at the western end of the Nile River Delta and between two water bodies: the Mediterranean Sea in the north and Lake Mariout in the south.

The lake, which used to be much larger, is filled with brackish water because it receives a large amount of sewerage output and discharge of untreated irrigation wastewater that comes from the western delta. Although it connects to neither the Mediterranean Sea nor the River Nile, in order to keep the water level in this landlocked lake below sea level, water gets pumped and discharged from the lake into the sea.

“Imagine if the pumps didn’t work for any reason, the water level in the lake would increase and overflow, which means that parts of southern Alexandria would be flooded by the water,” said Morsy, citing another infrastructure risk.

Morsy believes that researchers are turning their heads toward the sea level rise effect, when the real focus should be on the land of Alexandria:

“A tsunami will not remove Alexandria from the map. Tidal waves will certainly cause damage. But what will swallow this city are earthquakes and land subsidence. We will go down to the bottom of the sea, just the way it happened before.”

The Mermaid of the Mediterranean

The spot where Alexandria was constructed is playing a vital role in the city’s sinking scenarios. It dates back to 331 B.C, when Alexander the Great chose to build a city surrounded by two water bodies: the Mediterranean Sea in the north to make it a trade center, and Lake Mariout to the south, where he directed the Greek architect Dinocrat to design “Alexander’s Harbor.”

But the chosen location was a barren area. So the engineer needed to establish a complex, intelligent system to supply water from the Nile through canals, and then distribute water through a branched pipeline system and store it in underground tanks.

Parts of this old pipeline system still exist but are not functioning, as the new city is built on the top of the many ancient cities that came ahead of it, “And this is in itself another cause of subsidence,” said Torab.

“If you are living in Alexandria, it will be normal for you to suddenly pass by a big hole in the middle of a road you are used to walking on every day, or see a building with visible cracks. It is an obvious form of land subsidence,” Morsy said.

This issue inspired the Goethe Institute in Alexandria to join the project “Atlas of Mediterranean Liquidity,” which aims to show the impact of climate change on the Mediterranean through interactive maps and artwork.

Morsy contributed to the project. He sees it as a good way to raise awareness on how the city water sector was historically managed, and the challenges the city is going through. All is done through an interactive map done based on historical maps and city plans.

The ancient Alexandria was also built on limestone coastal ridges covered by a layer of clay, then a layer of the Nile river silt accumulated through the years. These landforms added to the fragility of the land toward subsidence, Morsy explained. The ancient Alexandria was also built on limestone coastal ridges that were covered by a layer of clay, then a layer of the Nile river silt that was accumulated through the years and these landforms added to the fragility of the land toward subsidence, Morsy explained.

Land Regression

Before reaching the Mediterranean, the Nile divides into two branches, Damietta and Rosetta. The number of branches is not clear, but they used to empty themselves in the Mediterranean Sea. One went through Alexandria even during the time of Queen Cleopatra. The blockage of the “Canopic branch,” due to the lack of maintenance, affected the sediment supply to the delta and the shoreline, which was vital for compensating the soil that got swept away by the waves, and caused land regression.

“Since the construction of the High Aswan Dam (HAD) across the Nile at Aswan in 1964, fresh water and sediment delivery to the coast of Alexandria declined every year. Because of the absence of sediments, the rates of soil erosion, land subsidence and groundwater salinity increased. This led to losing some lands to the sea, and we will be losing more,” said Ahmed Radwan, professor at National Institutes of Oceanography and Fisheries of Egypt (NIOF).

Daniel Jean Stanley and Andrew G. Warne published a well-recognized paper, “The Sea level and Initiation of Predynastic Culture in the Nile Delta.” They mentioned that, since 1964, essentially no sediment has been transported by the Nile River to the coast and also concluded that the Nile Delta “… is no longer an active delta but, rather, a completely wave-dominated coastal plain along the Mediterranean coast.”

He added that, without this dam, Egyptians would have survived neither the Nile flood, which killed hundreds of souls, nor the drought that hit the east African countries in the late ’80s and early ’90s: “The HAD was the real engine behind the development that happened in the country at this time.”

Land Reclamation

Radwan lives in Alexandria. He witnesses the coastal protection project that gets implemented by the government every day, and researches many hot spots. He believes the government’s reclamation and nourishment efforts are the safeguards for much of the coastland we are witnessing today:

“Let me give you an example. Abu Quir bay Headland is gained from the sea. Without the governmental effort to fill the gap in sediments, the area would have been lost to the sea. This is why sand feeding is important – to compensate for what nature was doing and bring in some ecological balance to the area that was lost to the sea with soil, cements or rocks.”

Between 1987 and 1994, artificial beach nourishment projects were implemented at Abu Qir, Stanley, El Asafra, Mandara and El Shatby beaches, with and without concrete jetties.

According to the UNESCO report, every year, 20-ton blocks are dumped into the water to protect the Corniche (road built along a coast) wall from wave action and seasonal winter floods.

“Land nourishment is not a permanent solution,” said Hisham Elsafti, who participated in the design and evaluation of many projects in marine civil engineering in Alexandria as a researcher at Alexandria University.

Elsafti works for the Department of Hydromechanics and Coastal Engineering at Leichtweiß Institute for Hydraulic Engineering and Water Resources of the Technical University of Braunschweig in Germany. He explained that “soft” solutions like beach nourishment might be more favorable because the global direction nowadays is to implement an Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM). It is an interdisciplinary, iterative approach for sustainable use of the coastal zone combined with nature-based solutions, sometimes also referred to as building/engineering with nature.

He gave an example of nature-based solutions supporting local coastal ecosystems to protect the coast, “in Indonesia, the country is using mangrove forests to dampen tsunamis’ damage to its coast.”

Hard and Soft Solutions

In 1984, the American engineering services company Tetra Tech, Inc. developed a Shore Protection Master Plan (SPMP) for the Nile Delta Shoreline and Alexandria for the Shore Protection Authority (SPA) of Egypt. It designed specific schemes for 13 selected shore protection projects, which were then categorized as “first priority projects,” and “second priority projects.”

The solutions applied by the Egyptian government are mostly “hard engineering solutions.” It is a well-known technique to protect its shoreline by placing coastal concrete armor units that change the patterns of seabed erosion and siltation for a long distance along the shore, as Elsafti said.

Before the soft and hard engineering solutions, Alexandria used to get its shore protection from two natural sources, the long shore parallel breakwater called “Pharos Island,” an island composed of a series of ridges. The Nile and the Litani—especially the Nile river—were significant in supplying sediment along the shore and filling the deficiency in the coastal sediment budget.

Humans tried to mimic those natural islands, and make artificial islands through land reclamation. Part of the supposed benefits of those islands is protecting the main shoreline. The government reclaimed a big part of the shore in Alexandria. In the north coast, and in Al-Alamein city to the west of Alexandria, a big project of land reclamation took place, aiming to build more than 25 high buildings, each including more than 41 floors.

“The benefits of those projects are economical but their relation to coastal protection is limited,” said Elsafti who also explains how any human interference in nature should be studied well, in order to avoid fixing a problem in one location only to cause problems in others.

He added that if sand nourishment is done at a place in the sea where the sand doesn’t belong, then the sand will shift from that spot, and sediment in another. “This is why any sand nourishment project takes into consideration the annual sand feed process.”

The Shore Protection Authority released a report titled “Adaptation to Climate Change in the Nile Delta through Integrated Coastal Zone Management.” It mentioned that “even if these measures—of coastal protection—were fully in place some of them may eventually prove to have negative impacts without a proper understanding of longer-term coastal dynamics associated with climate change. Therefore, more complex (mixed) approaches are required to increase the robustness of the coast and ensure sustainable long-term adaptation.”

Unlike the old city of Alexandria, the new Al-Alamein is considering coastal protection mechanisms throughout the construction process. During my visit to the place, I witnessed the large scale of engineering coastal protection work even before the completion of the construction.

The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) mentioned that the Egyptian government has committed $200 million to hard coastal protection at Alexandria and adopted integrated coastal zone management for the northern coast, including jetties, groins, seawalls, and breakwaters to combat beach erosion. “Recent activities include integrating SLR (sea level rise) risks within adaptation planning for social-ecological systems, with special focus on coastal urban areas, agriculture, migration and other human security dimensions,” says the report.

Lack of Coordination

Working as climate change advisor at the technical office in the Ministry of Environment and Environmental Affairs Agency has given Nadia Mohamed Elmasry a chance to witness what is happening on the ground to save Alexandria from sinking.

In 2017, she was involved in a project with the Public Authority for Shore Protection on a project to map the hotspots that urgently need the construction of tide breakers, to decrease erosion in these areas.

“After finishing the study, we noticed that some spots got eroded more than our expectations. Does this mean that the study was wrong? No, there were some unplanned development projects not included in our study, and they were built without considering the erosion map, such as the North Coast Compounds and new Al-Alamein.”

This explains why the beach looks different before and after the establishment of the compounds oin the north coast. “Before the construction you could see a sandy, beautiful beach. But after it you will notice the sudden appearance of a rocky beach,” said Elmasry.

She explained this normally happens when extensive engineering projects take place in the sea—such as those undertaken to create yacht marina or jetties—without studying the erosion rates, the shoreline change pattern and the tidal movements. These affect the tides’ direction and the erosion pattern, and cause high erosion rate in one place and increase in sedimentation in another one.

Elmasry opened the map and pointed her finger at the coastline of Alexandria and northcoast and said:

“Look at this shoreline. Some spots here were under high threat, but the situation in those spots improved a lot. Unfortunately some other spots deteriorated. I believe it’s not because of the lack of environmental studies, but the lack of cooperation between the different entities.”

The Egyptian government is facing this threat from many quarters. At the top of the list come the Egyptian Coastal Research Institute and the Egyptian Public Authority for Shore Protection, whose roles are to monitor the evolution of the Egyptian coasts to determine the near shore zone changes of the coasts. They predict future changes in the coastal zone by using mathematical models to select the most economical and effective protective measures.

They also prepared the Alexandria Integrated Coastal Zone Management Project (AICZM) under climate change scenarios, along with other entities such as the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) which, they say, is providing the most efficient, low cost and effective control works to protect the heavily populated areas.

Who Can See the Sea?

Alexandria has gone through many phases of abundance and deterioration throughout its modern history. The city lost its prestigious place and importance as a cultural and commercial center, and its population notably declined. It happened just before the earthquake that hit the city and caused big damage to its infrastructure and buildings, including ruining the lighthouse around 956 AD.

But gradually the city regained its place. Now it is facing the opposite problem. An over-growing population shrunk the space for houses, which encouraged the construction of tall buildings by the seaside. Many cafes and restaurants sprung up on the now-concrete shore, and together all these structures added big pressure on the infrastructure and the land.

If you plan to visit the remarkable coastal city, there is a high chance you won’t be able to see the sea, or sit on a sandy shore. The coastline mostly consists of big blocks of concrete to protect the shore from erosion, with either cubic shapes or four-legged quadripods, or restaurants and cafes that will stand as a barrier between you and the sea view.

Elsafti clarified that coastal defenses along Alexandria’s coast were developed to support the widening of the Corniche by means of a revetment structure. These sloping structures erode the power of the waves behind them, but it is not related to SLR. “Revetments should be designed to prevent the seepage of fine soil material from the large gaps between the coastal concrete armor.”

He described how hard it used to be to move from one place to another using the Corniche road before the widening, and the shore nourishment that had been done years ago, “Traffic used to be a nightmare. The Corniche widening project helped a lot in facilitating the movement.”

Yasmine Hussein is a research director at the Human and the City for Social Research (HCSR), and her family members are old residents of Alexandria. Before talking about the city, she took a deep breath and, with a voice full of sadness, she said: “Yes, there used to be sand and shores, and walking on the Corniche was a basic outing for Alexandrian families. I built hundreds of sand castles just like all kids my age at the time. Those childhood memories are gone, and now, there is almost no shore. There are either concrete blocks, or restaurants and cafes constructed on the shore. The generation that witnessed Alexandria 15 or 20 years ago is feeling a great amount of sorrow and nostalgia.”

Hussein contributed to many studies about Alexandria. One of them is “Alexandria Corniche: Between privatization and the right to see the sea,” which investigated how the highly populated city of Alexandria, with its more than half a million inhabitants nowadays, lost most of its shores. She attributed this loss to the urbanization projects implemented without enough consideration to the environment, or before the completion of the project’s environmental studies.

“The threat comes not only from sea level rise but other factors, such as land subsidence and the threat of earthquakes. This is what happened in the past and led to the sinking of this city twice, in 956 AD and 1303 AD,” said Hussein.

“We are inside the climate change, not waiting for it to happen,” Hussein added with a strong voice, “We used to have seasonal rain in the winter. It is locally called ‘NOAA’. It is more intense now. The rain is heavier, the storms are faster, and the tides are higher. This situation is causing damages; almost every year we are witnessing (extreme weather events).”

She explained that Alexandria faces two challenges. The first is repeating the same scenario and sinking again by tsunamis or earthquakes, and the second is the seasonal sinking every winter because of the extreme weather events.

One of the challenges that adds to the fragility of the city is the heavy construction and housing projects that took place everywhere: “This is a heavy weight on the land. It is an unbearable load … that doesn’t consider the environment or climate change.”

This increased privatization also takes a toll on public space. In 2019, the research center HCSR launched a campaign called, “Alexandria can’t see the sea,” to create awareness and encourage communities to get involved and be aware of the situation in their city before it’s too late. Hussein recalled, “We received good feedback from the community members. We asked people to send photos of the sea view to compare between the view in the past and now, collected those “before and after” photos, held an exhibition where we showcased what is going on the ground, and presented our studies.”

Top of the List

In their annual report, the IPCC said that “in the absence of any adaptation, Egypt, Mozambique, and Nigeria are projected to be worst affected by sea level rise in terms of the number of people at risk of flooding annually in a 4℃ (39.2°F) warming scenario.”

The report explored the potential damages due to SLR and coastal extreme events in 12 major African cities. The city of Alexandria in North Africa leads the ranking, with an aggregate expected damage of $36 billion and $50 billion under the moderate scenario, where emissions peak around 2040 and then decline.

The Egyptian Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation reports a sea level rise at an average rate of 1.8 mm (0.7 inches) per year until 1993. The following two decades, the water level rose by 2.1 mm (0.8 inches) per year, and since 2012 it reached 3.2 mm (0.12 inches) per year. The Nile delta is reported to sink at the same rate, which amplifying the negative impacts of SLR.

But Morsy believes that a satellite view might not give the most accurate data regarding the effect of SLR in Alexandria, “We need studies that will focus on small scales and local environmental aspects and their effects. The effect of climate change and SLR is not equal everywhere in Alexandria.”

Morsy agreed that sometimes researchers focus on the worst case scenarios to encourage governments to take actions: “There was an old study that predicted that Alexandria will sink in 2023. But look how the situation is now; the city didn’t sink.”

He said that if the city is going down it’s because of all the factors that get mentioned:“Every thousand years the city goes down by one meter.”

Morsy leaves me to dive again and swim beside the ancient Alexandria. His dream now is to live on a ship in the Nile in Aswan, so that if a flood happens he will be safe in his Ark.

Rehab Abdalmohsen is an independent science journalist and water reporter whose work has appeared in ScieDev.net, @NatureNews, the Niles magazine, among others.

‘U.S.-Africa: How the Peoples’ Struggles Connect’: Second Panel of African People’s Forum

Editor’s Note: This panel discussion was produced by the African Peoples’ Forum.

Paul Sankara, consultant, activist and brother of assassinated Burkina Faso leader Thomas Sankara; Eugene Puryear, community organizer and host at BreakThrough News; Erica Caines, a Black Alliance for Peace Coordinating Committee member, co-editor of Hood Communist and founder of Liberation Through Reading; and Nebiyu Asfaw, co-founder of both the Ethiopian American Development Council and the #NoMore Movement discussed connecting African peoples’ struggles across the continents at the first-ever African Peoples’ Forum. The event was held December 11 at the Eritrean Civic & Cultural Center in Washington, D.C. Journalist Hermela Aregawi and activist Yolian Ogbu moderated.

The first panel can be viewed here.

TF editor Julie Varughese reported on this event being held to counter the Biden administration’s U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit.