“There’s a great disparity between what’s being articulated by this radical feminist queer trans Black movement and the language of party politics, and the electoral choices, which are so incredibly impoverished they’re not choices at all. The demand to defund the police was taken up because there’s been a movement unfolding for decades, an analysis that has been in place […] It’s not a surprise that so many of the people in the street are young. They’re in the streets with these powerful critical and conceptual tools, and they’re not satisfied with reform. They understand reform to be a modality of reproducing the machine, reproducing the order—sustaining it.”

Saidiya Hartman’s description of the latest iteration of the Black Lives Matter rebellion captures how millions of activists, led by Black queer and transwomen, have stepped into the breach caused by a multilayered crisis of legitimacy of state institutions.

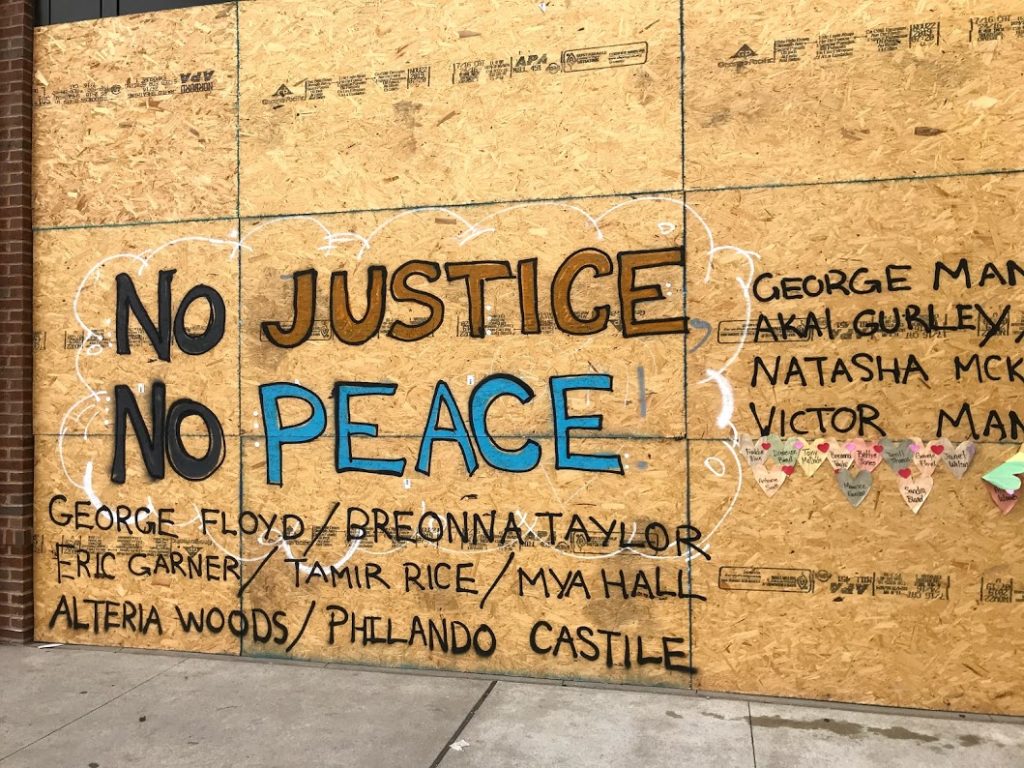

This crisis was brought on by the police and vigilante murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Tony McDade, a neglectful COVID-19 response, and economic pain throughout the US. The ongoing responses from people in the streets invoke what Frances Fox Piven calls “disruptive power.”

The disruptive power of this summer’s rebellions has unleashed political and cultural creativity, and expanded our horizons of what participatory democracy and public safety might look like.

Protesters have leveraged this moment to retake privatized and militarized spaces, including the memorial to victims of police murder and brutality in Washington, D.C., the shrine for Breonna Taylor at Jefferson Square Park in downtown Louisville, and anti-law enforcement murals and graffiti stating “fuck 12” and encouraging people to “warn a brother” upon the sight of police painted on boarded up businesses in cities like Columbus, Ohio.

In addition, to the consternation of the Trump administration, people have engaged in the practice of taking back enclosed and privatized spaces like the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) in Seattle and the Floyd memorial in Minneapolis, restoring them as commons, even if momentarily.

Confrontations with police and attacks on property operate symbiotically with various strategies and tactics that activists and organizations have devised to evade state and electoral capture. These include calling for non-reformist reforms, realigning public institutions with radical organizations, calling for community control, and engaging in collective, participatory efforts at re-envisioning public safety.

Together, these strategies point to a goal that scares many, especially those close to institutional power: delegitimizing or abolishing the current system of law enforcement and prisons, whether it is local police and jails, or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and border detention centers.

Radical demands and non-reformist reforms

Dissatisfaction with police reforms like body cameras, bias training, and state-defined legalistic concepts of “police accountability” in a system that continues to murder Black and Brown people has pushed rebels and organizers to advance more radical demands, which they say are required to protect Black life.

The New York Police Department’s 1993 chokehold ban did not prevent officers’ fatal use of it on Eric Garner in 2014. Activated body cameras did not prevent Minneapolis police officers from fatally pinning George Floyd. Thus, organizations and groups such as the Movement for Black Lives, Minneapolis’s Black Visions Collective, and the “Detroit Will Breathe” movement are calling for “non-reformist reforms” in the wake of this summer’s protests.

Non-reformist reforms seek to short-circuit the “reform and revolution” binary. New Left intellectual André Gorz sought to challenge this binary in his 1967 book, Strategy for Labor. Gorz wrote: “The question here revolves around the possibility of ‘revolutionary reforms,’ that is to say, of reforms which advance toward a radical transformation of society. Is this possible?”

In an effort to disrupt and delegitimize the current system of justice, activists are posing similar questions. “Are the proposed reforms allocating more money to the police? Are the proposed reforms advocating for MORE police and policing (under euphemistic terms like ‘community policing’ run out of regular police districts)?” asked longtime prison abolitionist and organizer Mariame Kaba in a 2014 article.

“People are rejecting all the reforms that have been regurgitated over the past several years and that have not kept Black people safe. These reforms have expanded police budgets but have not kept police from killing people,” Detroit Justice Center (DJC) founder and executive director Amanda Alexander told me in a phone interview. “Instead, [people] are saying we need to defund and abolish police. The test I always come back to—does the proposal expand the legitimacy or funding of the police, or does it move us towards defunding and dismantling the police?”

The demand to “defund the police,” which has come to symbolize this uprising, is clearly a “non-reformist reform.” The rallying cry to defund the police follows a particular logic consistent with abolitionists’ long term goal of undermining police power and reducing harm in the near term. As Kaba recently stated in a New York Times editorial “…here’s an immediate demand we can all make: Cut the number of police in half and cut their budget in half. Fewer police officers equal fewer opportunities for them to brutalize and kill people.”

There has been much debate in the media and among scholars amid the provocative call to defund police. Critics say defunding the police will lead to “lawless anarchy,” or that it would lead to further harm. Others argue for a “reimagining” of how police operate in society, which could entail advocating for police to strictly handle investigating criminalized activities and soliciting more community input on police performance.

What these critics miss is that the call to defund the police is an expansive demand that underscores the limits of reforms: it exposes law enforcement’s power and the political establishment’s preference for state violence over community care and economic justice.

This is why the demand to defund the police has the capacity to disrupt the reform-revolution binary.

For many abolitionists, defunding the police is a direct path toward reducing harm immediately. Many abolitionists believe that the more police have contact with Black and Brown people, the greater the chance of harm. As human rights lawyer and abolitionist Dereka Purnell recently told Cosmopolitan in an interview, “At its core, police abolition is about trying to find ways to solve harm without relying on cops. Defunding—taking money away from the police and giving it to social workers, counselors, and other resources—is part of that process,” she said.

We know the criminal justice system will fill prisons as long as they exist. So, one must take the defund the police demand to its logical conclusion—eliminating prisons and police.

“Defund the police” is not just a call to dislodge police power from the center of governance, it’s also a call for more participatory democracy, for people to rethink our priorities, and to dismantle and realign our institutions and communities around more humane principles.

In the words of activist and scholar Angela Davis, “abolition is really about rethinking the kind of future we want, the social future, the economic future, the political future. It is about revolution…” For activists seeking to build a police-free world, advocating for non-reformist reforms is a strategy to achieve practical reforms that do not further legitimize the police without foreclosing revolutionary possibilities and succumbing to the demobilizing forces that accompany state capture.

The power of Alignment

The Minneapolis city council’s pledge to dismantle the police department at a rally organized by the Black Visions Collective in early June confirmed what the burning of the third precinct told observers around the world: law enforcement in the city and throughout the U.S. faces a deep crisis of legitimacy. While it is clear the nationwide and global uprisings accelerated the move toward abolition, Black Visions Collective member Yordi Solomone told me in a phone interview that the Minneapolis city council’s promise was the product of community organizing and what she calls “alignment.”

One goal of alignment in Minneapolis and St. Paul has been to bring together disparate political groups and activists who share the broad objective of, as Solomone describes it, “keeping Black people safe and rebuilding communities simultaneously,” even if “folx…may not be in the same space ideologically.”

This motivation grew out of years of organizing by Black queer and trans folx, who founded Black Visions Collective in 2017. This coalition of Black organizations conceives of itself as a formation grounded in the principles of “healing and transformative justice.” Drawing from the deep well of Black queer and feminist theory and Black radicalism, this coalition relies upon a flexible “powerful campaign” strategy.

According to a video posted on the Black Visions Collective website, this strategy “can look like delivering mobilization and action goals as part of a national coalition in which Black lives are centered,” while at the same time working towards “visioning and leading targeted collaborative local campaigns that advance a concrete impact…”

In addition to developing a political program linking environmental, economic, and transformative justice; Black Visions Collective engaged in direct action, confronting police participation in Pride, and waging campaigns to redistribute resources from the city’s police force.

George Floyd’s murder and the uprising that followed reinforced the need for alignment among groups around policing and public safety. As Solomone explained, “Black Visions brought all of the Black organizers in Minneapolis and St. Paul to do work that is more collaborative in a way that is not in silos because this [anti-state violence organizing] was already taking place.”

Thus, Black Visions and other Minneapolis and St. Paul based groups successfully used the moral authority generated by protests against Floyd’s murder to advocate for transformative policies from a position of strength, while aligning themselves with supportive elected officials and policymakers, who activists pushed to publicly declare they would disband the police. From there, Black Visions seeks to use alignment to position itself as a countervailing force against the Mayor and the police force, in the struggle to change the city charter (#changethecharter) to “eliminate the police.”

No matter how radical their ideology, politics, and theory of social change, organizers must ready themselves and their groups to ride the wave of massive protest toward their goals. Black Visions Collective’s willingness to pressure and engage city council allowed the collective to take advantage of the rupture created by George Floyd’s murder, the burning of Minneapolis’ third precinct, and the massive protests that followed.

Activists in Minneapolis quickly escalated their calls to defund the police by launching #DefundMPD, which helped spark a larger national conversation about police funding and local budgetary priorities. Solomone reports that members of the coalition understand that their successful push to secure a public commitment from the city council to disband the police was not “an isolated incident.”

Organizers in Minneapolis and St. Paul also recognize that Floyd’s murder, the protests, and their calls to defund the police has shone a spotlight on their work. “The world is watching, not just Black Visions, but Minneapolis in general,” Solomone said.

Envisioning a narrative for a new society

Movements need narratives—a story told through an analysis of a social problem and its history, their political traditions, principles, and solutions; a theory of, and path towards, and social change. For many activists, this journey moves towards what Kaba calls the “horizon of abolition.”

Latinx-led movements have worked in the last decade to resist family separation policies, extend sanctuary to undocumented people, and to abolish ICE. Some organizers and intellectuals have encouraged those concerned with anti-Black state violence to pay more attention to the connections between the violence of immigration enforcement and the policing of protesters. The Trump administration’s deployment of Homeland Security Border Patrol agents to protests in Washington DC, Portland, Seattle, and Milwaukee have brought links between immigration enforcement and state violence against Black and Brown people into sharp relief.

“White folks see ICE as the organization that separates children from their parents… White allies often do not see the police as the people who are separating parents from their children. To them, the police have always served some kind of helpful community function,” said William D. Lopez is a public health scholar-activist and author of Separated: Family and Community in the Aftermath of an Immigration Raid.

Lopez recognizes that people of color have always viewed immigration enforcement and the policing of Black people as connected, even as many white Americans did not until the Department of Homeland Security started targeting protesters. But, as he went on to explain, “to communities of color, ICE and police are doing the same thing. In communities of color, ICE is surveilling you; the police is surveilling you; ICE is separating you; the police are separating you.”

Recent whistleblower reports of ICE conducting mass hysterectomies calls further attention to the intersectionality of state violence in this country’s long history of forcibly sterilizing Black and Brown women.

Organizers working to abolish ICE argue for the development of new, and more expansive, narratives supporting transforming public safety. In an email, I asked We the People Michigan Deputy Director and DACA recipient Maria Ibarra-Frayre about making sure abolition remains central to organizing against state violence. “In order to keep the movement to abolish ICE and other racist immigration enforcement going we have to create different narratives for what our community needs,” she responded.

“Popular narratives and culture drive our movements by setting the agenda for what the masses believe could be possible. We have to be ready with a narrative of a different world, a narrative that inspires hope, dignity, and liberation for our people,” wrote Ibarra-Frayre. “We can’t craft our narratives to what is ‘politically feasible’ because otherwise we will never be inspired to reach for more.”

Activists and organizers have been building theory and language to counter the law and order narrative that’s dominated discourse around crime and policing over the last forty years.

For example, activist intellectuals like Ruth Wilson Gilmore have worked to sharpen understandings of racism. “Racism is the state-sanctioned and/or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death,” she wrote in her influential 2007 book Golden Gulag. Writers such as Heather Ann Thompson, Elizabeth Hinton, Michelle Alexander, Saidiya Hartman, and many others have provided activists with concise histories of the expansion of law enforcement, mass incarceration, and the rampage of racist state violence in the U.S.

Meanwhile, activist scholars like Davis, Wilson Gilmore, Kaba, and Dean Spade, as well as groups like Critical Resistance offer a praxis for abolition-democracy, a term sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois coined in his magisterial history of Reconstruction, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880.

Abolition-democracy refers to the method of dismantling violent, oppressive institutions and reconstructing society’s systems of public safety and law, politics, and economy around principles of participatory democracy and transformative and restorative justice.

One way for advocates of transformative justice to prepare for the acceleration of a movement, especially one towards abolition, is to build a new narrative through community political and mobilize collective envisioning as an explicit expression of participatory democracy. In abolitionist circles, envisioning is a collective exercise that encourages community members to conceive of public safety in an expansive way.

Envisioning a more humane system of public safety can start with questions like: “What resources would you need to feel safe?” Or—“What would you do with the resources that are freed up after defunding the police?”

An envisioning process can be an exercise in participatory budgeting, a concept that the Brazilian Workers’ Party devised during the 1980s. Anarchists like Michael Albert have advocated for a version of this vis a vis participatory economics. Participatory budgeting involves bringing people together to decide collectively on how and where they should invest resources. Abolitionists draw on this tradition when they ask community members to imagine how they would spend money redistributed away from criminal justice institutions.

DJC Executive Director Amanda Alexander outlined this process to me by describing how the state has been divesting from social programs over the last several decades while investing in punishment, policing, and prisons. “We ask people, ‘How would you invest money in order to feel safer in your neighborhood?’” said Alexander. “No one says we need to build a new jail, or we need more police. Instead, they have a list of ideas around transit, affordable housing that’s accessible for disabled people, fair pay for teachers, fixing water pipes in Detroit schools to make sure drinking water is safe, [and] restorative justice programming. Many of these things, people realize, would actually create safety.”

One of the fears of disbanding police in a capitalist system is that “chaos and anarchy” would ensue. The process of envisioning belies this fear by demonstrating that, according to Wilson Gilmore’s formulation, “abolition is a presence.” Rather than an absence of police, prisons, and what many assume as “law and order,” abolition also represents the presence of “vital systems of support that communities lack.”

Through an envisioning session, as Alexander described, defunding and disbanding the police and closing prisons could come to mean investments in infrastructure and institutions necessary for people to meet their needs: more affordable, if not free, education, quality public transit, affordable housing and shelter for all, universal health care, food sovereignty, and safety. Pursuing these goals would surely be disruptive, but it would also connect people together, as they work to devise new ways of practicing justice and preserving dignity.

All of this leads to another question: if police and prisons were abolished, what organizational form practicing justice would actually take? Would it be akin to a “Citizen’s Peace Force,” as Huey P. Newton once suggested? Or would it resemble the creation of a “Community Safety and Violence Prevention Department” as called for by Black Visions?

In Detroit, the DJC has been supporting efforts to create a metro Detroit network of restorative justice practitioners. Alexander said local organizations seek to mobilize already-existing community resources and people “doing work already around de-escalation, mediation, and restorative justice to build out systems that we need that can address or prevent harm.”

Envisioning an abolition-democracy in the U.S. suggests not that we “redefine the police,” as the editorial boards of the Houston Chronicle and The Buffalo News advocated after the deaths of George Floyd and Daniel Prude. It is urgent that we deconstruct our understandings of the roles of policing, prisons, and surveillance. As Solomone from the Black Visions Collective told me, communities and activists should “co-create” models of political education.

Members of #PoliceFreePenn: An Abolitionist Assembly, which formed this summer to “abolish policing and transform community safety at the University of Pennsylvania” also cite the importance of political education work. Historian and #PoliceFreePenn organizer Anne Berg told me in an email that “unpacking the model of ‘safety’ that policing is grounded in comes first.”

Those working on the front lines of movements for transformative justice and toward abolition understand the gravity of persistent calls for a “revolution of values” made by radicals like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Grace Lee Boggs.

Calls to defund the police, activists’ demands for non-reformist reforms, and grassroots organizing grounded in principles of transformative justice are a bridge toward that revolution.

To get there, we have to carry out collective conversations that address how we protect each other from harm through a practice of restoration, rather than retribution, and examine how the implementation of justice strengthens our communities rather than depleting them. This work requires asking questions that cannot be meaningfully addressed within the current political and institutional system in the United States.

Abolitionists believe the possibility of meeting peoples’ needs and restoring common property would allow communities to replace notions of security with safety, favor collective care over cops, and privilege democracy over domination. These principles, especially with the restoration of the commons, run counter to the imperative of the current criminal justice system to defend and protect private property rights. Activists can resist state capture by maintaining the democratic and anti-capitalist thrust embedded in their long-term vision.

The long view

Over the course of our conversation, Solomone reminded me that radical political movements do not move in a straight line toward progress. Many abolitionists recognize that police, the courts, prisons, immigration detention center, and ICE will not disappear overnight. “It’s not a sprint,” Solomone told me, rather, the struggle is “more of a long-term thing.”

This is why it is necessary to take a long view. Struggles for abolition, and abolition-democracy, are literally rooted in enslavement, racial capitalism, and settler colonialism. “How do we think about [abolition] as it goes beyond the urgency of the moment?” Solomone asked rhetorically. Many activists and scholars who work on abolition today rely on the powerful idea of abolitionist time.

“Abolitionist time is a type of revolutionary time. But rather than stop the world, as if in an absolute break between now and then, it is a daily part of it,” wrote Avery Gordon in her 2017 book Letters from the Margins: The Hawthorn Archive. “Abolitionist time is a way of being in the ongoing work of emancipation, a work whose success is not measured by legalistic pronouncement, a work which perforce must take place while you’re still enslaved.”

Abolitionist time takes the long view, and does not operate on the same rhythm as congressional and presidential election cycles. Nor are established institutional arrangements the main thoroughfare to the horizon activists strive to reach.

Obviously, there are pitfalls when trying to organize a radical political movement in the U.S. For one, the Trump administration is telegraphing a crackdown on the protests and the movement if the president wins another term.

The Democrats, on the other hand, might seek to capture the movement by calling on protesters to support passing a version of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act that Karen Bass and other Democrats wrote in response to the uprising. The bill features reforms that have not stopped police from killing citizens in the past. It also calls for the creation of “public safety innovation grants,” which would allow communities to explore alternative approaches to policing. This legislation fails to de-center law enforcement and incarceration in the legal system. Nor does it seek to defund or dismantle the police, or recognize the outsized political power of law enforcement.

The difference between the Ferguson uprisings in 2014 and this summer’s protests seems to be activists’ and groups’ intense skepticism of what they believe are superficial police reforms. Today there is also a widespread distrust of elected officials, whether in local, state, or federal government, as they tend to be beholden to police power.

Over past years, organizers have developed a means and strategy to avoid falling into the trap of relying upon established political parties to devise and implement legislative “fixes.” They question whether or not reform proposals seek to undermine police’s outsized political power, demilitarize, defund, and disband local and federal law enforcement institutions, and close prisons and detention centers.

The emphasis on stifling police power, the use of disruptive power, the advancement of non-reformist reforms, and the work of alignment are central to the effort to avoid capture by the state, and to try to build new narratives that fundamentally challenge the dominant view of how people in the U.S. think about public safety.

Today, an intergenerational movement for Black Lives is advancing a call for innovation in democratic practice—one that is collective, experimental, healing, and cannot be bound within the confines of the existing system. There is no doubt that fulfilling a 200 year struggle for abolition-democracy will be disruptive and imperfect. But living in a society where Black, Brown, and Indigenous people are at constant risk of state, extra-legal, and interpersonal violence is already disruptive, full of horror and pain, and extremely imperfect. Thus, why not dismantle and rebuild before this system kills us?

Taking the time to dismantle the old, violent institutions, and collectively devising new ones simultaneously is no small task. The prospects of building this work are truly scary, especially as current systems work daily and use extreme violence to foreclose any other possibilities. But like the abolitionists that came before, not everyone currently engaging in the process of freedom-making will be folded into the state and its political culture. Rather, dismantling the system, piece-by-piece, will unfold in abolition time.

Author Bio:

Austin McCoy is an Assistant Professor of History at Auburn University. He is also an organizer, participating in anti-police brutality campaigns and working for racial justice.