By Kim Poole | Founder, Teaching Artist Institute

When I stepped through the gates of the Pontifical Urbaniana University this past May, I carried more doubt than certainty in my bag. For three days, during African Liberation Weekend, I watched a global circle of scholars, seminarians, artists, prophets, priests, and everyday people do something rarely done within these ancient Vatican halls; we told the truth out loud about Reparatory Justice for Africa and the African Diaspora. We demanded that the Church help deliver it.

During this African Union’s first Year of Reparatory Justice for Africa and the African Diaspora, we navigated the grounds that have shaped the Church’s moral authority for centuries. The Vatican Symposium was more than an academic talk event where people pontificate ideas about what they want. Rather, it was a healing in practice that can no longer be ignored.

When we first set this vision in motion, I reached out to the seminarians’ student group Omnes Gentes, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom Italy [WILPF], and the Global Circle for Reparations and Healing. Omnes Gentes, a Vatican-based intercultural student organization, is grounded in the mission of building authentic global dialogue within Catholic formation. They brought the heart and energy of young clergy in training who believe in a Church that listens and evolves.

I remember how the road turned and twisted before it opened. The WILPF International Secretariat told me they could quietly share news of our gathering with members, but felt they could not publicly stand beside us inside the Vatican’s walls. Their reluctance reflected a long-standing tension. WILPF’s historic secularism, born from its early 20th-century pacifist roots, has long resisted direct association with institutions like the Catholic Church, particularly because of the Church’s colonial entanglements. But just like water shapes the ground, Patrizia Sterpetti of WILPF Italy showed me something stronger than policy or historic pain. She showed me the courage to heal our future. She said, “you can count on me” and I felt that promise deep in my chest.

The Global Circle for Reparations and Healing too, at first, felt the timing was not right. Pope Francis had just passed away that Easter. Many wondered if this sacred pause would swallow our moment. But faith has a way of growing through hesitation. Less than a week before we flew, Kamm Howard called to say they were coming after all. The Global Circle for Reparations and Healing, a big-brain network of African-descended leaders from across the Diaspora, understood well the church’s amnesia. On July 18th 2022 they came to the Dicastery of Education and Culture to deliver a Presentment of legal claims for church liability in global African trauma that was never fully acknowledged.

That is partly how I knew the Vatican Symposium was never mine alone. It was faith with a pulse, quiet proof that this is God’s work and plan.

So we moved forward, through every twist and pause. Together we turned Pontifical Urbaniana University’s stone lecture halls into a sanctuary for truth-telling in the Vatican’s heart.

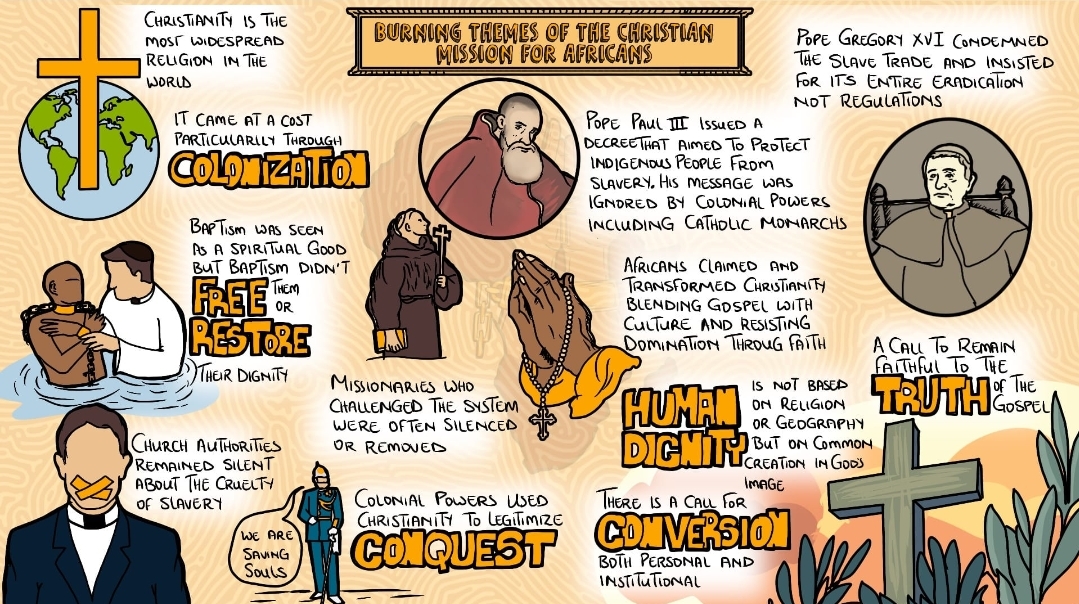

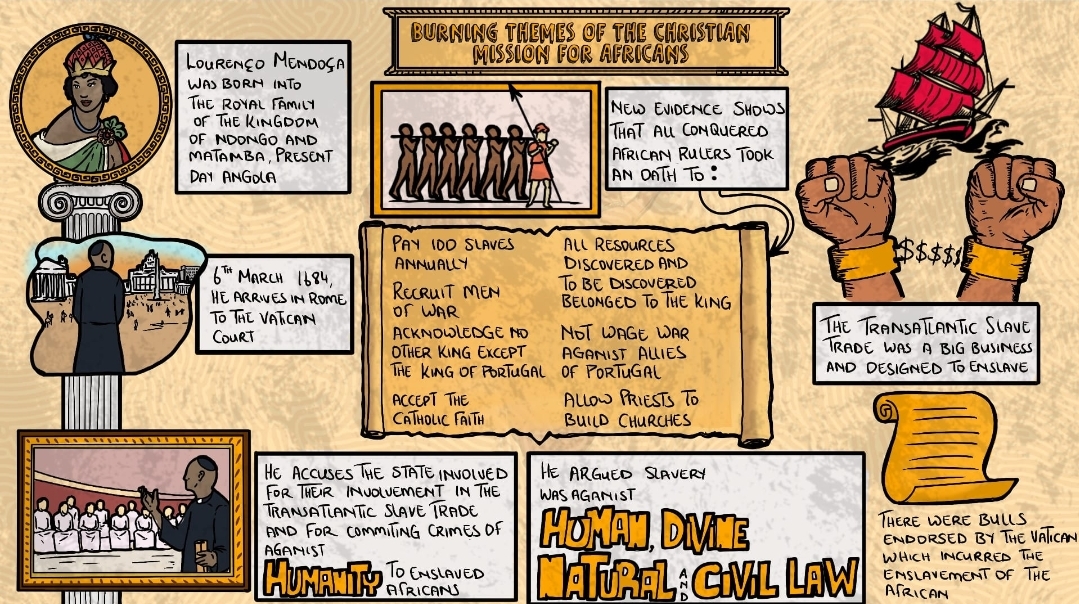

Across three days, we named the Church’s complicity in colonization. Everything from the Papal Bulls Dum Diversas of Pope Nicholas V in 1452 and Romanus Pontifex (1455), which gave divine license to steal African lands and bodies, to the silence that has stretched for centuries.

I listened as Dr. José Lingna Nafafé, professor at the University of Bristol, unlocked the buried story of Lourenço da Silva Mendonça, the 17th-century Angolan abolitionist who dared to petition the Vatican to condemn the slave trade centuries before Europe would even pretend to listen. Mendonça, born into royal Pungo-Andongo lineage (modern day Angola), exiled in Brazil and re-educated in Europe, went on to lead one of the earliest legal and theological cases for abolition, within the Church itself and the Atlantic world. His images alone could inspire an entire new concentration for seminarians ready to study truth, not colonial myth.

Global experts came from Chicago, Kentucky, from the UK, Kenya, Tanzania, Italy; each carrying proof that this is not just an African struggle but a glocal one. I watched Kamm Howard remind the room that Pope Leo XIV, who will soon ordain new priests, was from Chicago like him and carries African genealogical roots. That matters. It means the future of this institution carries a thread that cannot be cut off from our story.

Dr. Lewis Brogden spoke about the hidden intersections of faith and Black identity. Ana Miro of Tanzania said what about illicit flows of resources within Africa, that now we too are a part of the problem. Dr. Patrizia Sterpetti ensured that activists from across Italy were present. She told us how she has fought for decades to protect African refugees cast aside by Europe’s fortress walls.

One of the most sacred moments came from Lanishma Emmanuel Gbatar, a master’s student in missiology and interfaith dialogue. I watched him pause, close his eyes, and say: “In six years of seminary, this is the first time I have ever been invited to moderate any public dialogue, of any topic. That it is this dialogue about Reparatory Justice is no accident. This is God’s work.” Emmanuel told us that he will be ordained by Pope Leo XIV on June 27, inside these same walls. This conversation, he promised, will live inside the Church, not just at the gate.

And then came Stanislaus Obiakor, an Igbo graduate of Pontifical Urbaniana University, who stood and said he had left seminary because he “could no longer stomach the lie that ignored the divine nature of women.” Around him; local voices, young and old, Giovanna Graziano, Stanislaus Obiakor, Vincenzo Mazzola, Omar Diallo, Daoud Mahamat, Alessandro Triulzi, Steve Emejuru

When the last presentation ended, we did not pack up and go quiet. We held a Global Virtual Community Report-Back, where clergy, prophets, and everyday people carried the message forward. I watched Rev. Kobi Little of Deacons for Justice, Pastor Tom Schwind of New Covenant Tabernacle, Dr. Akil Khalfani of the Africana Institute, and Prophet Anyanwu Cox stand and declare that the Church’s historical amnesia must end with tangible action. They committed to being part of the coalition forming to do this work.

Cressandra Dunford, who opened every day with songs of praise, told the gathering that her hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, will embed our Reparatory framework in city policy across every sector. That is what faith looks like when it rolls up its sleeves.

One of the quiet miracles of this gathering for me was Erick Kiarie, our Teaching Artist Institute illustrator from Kenya. I met Erick just two months earlier at the Baraza Social Movements in Ghana. He had never left Africa, never seen Europe, and he told me it would be an act of faith if his visa was ever approved. I felt it too, so I bought his plane ticket before that visa was even in his passport. Two months later, he was standing beside me at Pontifical Urbaniana University, sketching our story in comic-book panels for the world to see. That is how faith travels, on a wing and a prayer.

A mustard seed, in truth I bought my own plane ticket before the Vatican ever officially approved the date. I didn’t even land in Rome until the morning of the event. I changed clothes in a bathroom stall, from my take-a-flight Momo into my Vatican presentation best, and rushed straight from the airport to the podium.

The Bible says faith the size of a mustard seed can move mountains. Thank God for that, because a mustard seed is all we had. Our printed banners, event programs, and Prayer for Reparatory Justice bracelets never even arrived in time. They are still crossing borders to find us. If you are reading this and want a printed program or bracelet to stand with us, we have plenty and every purchase keeps this work alive.

The ultimate takeaway from our gathering is my blueprint for interfaith healing. I call this truth-telling serum the Ukumbusho Cure, Ukumbusho meaning remembrance in Swahili. This blueprint for healing centers land return, nullification of colonial papal decrees, an official declaration honoring Africa’s place as the cradle of civilization and Christianity, especially the Ethiopian foundations of the faith. After one presentation, I raised the example of Ethiopia’s Christian heritage, the ancient kingdom of Axum, and the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela, as evidence of Africa’s central place in early Christian history. The Togolese professor who had just spoken responded simply, “That’s Christianity only for the Ethiopians.” His excellent presentation had used striking images to expose the Church’s historical tunnel vision, and in his words, I saw something deeper, a window into how tribalism shows up even in the Church. While the Ethiopian Church’s lineage is sidelined as too specific to be universal, the lily-white faces of Jesus and the rosy-cheeked angels in the Sistine Chapel are accepted without question. This hypocrisy lives in the architecture. It’s time to change that.

The Ukumbusho Cure calls for the replanting of African spiritual heritage in Church life and dedicating a permanent share of the Church’s wealth; including museum profits from inception into perpetuity to fund real repair. The approach is simple and impossible to ignore: Faithful & Future-Oriented. Actionable & Glocal. Sustainable & Land-Based.

As the African Union’s Year of Reparatory Justice moves forward, together we are praying with our feet.

Link to Vatican symposium summary:

https://gcrh.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Vatican-Presentment-Executive-Summary.pdf

https://youtu.be/VwxsGyPmBLk?si=n-wxFFotMHfUC4h8

About Teaching Artist Institute:

Founded by Kim Poole, the Teaching Artist Institute (TAI) is a global network of artists, scholars, and cultural workers using the arts as a tool for social transformation, cultural preservation, and reparatory justice. Learn more or join the movement at Facebook.com/TeachingArtist