Correction: A previous version of this article stated the United States owed a greater amount to the UN’s climate finance program.

If anyone expected ambitious delivery of climate finance given the rhetoric at the United Nations’ 26th Conference of Parties (COP26), they would be disappointed. Ongoing discussions regarding climate funding to help developing countries meet their obligations reveal serious limitations, according to experts Toward Freedom interviewed.

A meeting was held March 8-9 to discuss the next round of funding for the Global Environment Facility (GEF) Trust. The trust was established in 1992 to support developing countries to comply with international environmental conventions and agreements, like those related to climate change, biodiversity, chemicals, and waste and food security. Currently, discussions are on for the eighth round of funding.

Wealthy Countries’ ‘Ambitious Regression’

As of now, it looks like funding for climate action will be around $1 billion. This is only marginally better than the seventh replenishment cycle that allocated $800 million, about $200 million less than the sixth cycle.

“This is what ambitious regression looks like,” said Zaheer Fakir, one of the lead coordinators for the African Group of Negotiators on Climate Change (AGN).

Moreover, certain developed countries like the United States, Japan and Switzerland have proposed smaller allocations toward climate change in the GEF, while prioritizing other items like biodiversity and chemicals. Their argument is that while other entities—like the Green Climate Fund—could mobilize climate funding, GEF is the only grant-based, multilateral financing mechanism for other issues like biodiversity loss and chemical waste.

But developing countries don’t share this view, according to Fakir. Speaking for South Africa, he said the GEF should ideally scale up allocations for all areas—including climate change—because it is an entity through which funding is provided under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), too.

This is in line with an October 2020 COP guidance to the GEF that encourages GEF, as part of its eighth replenishment process, “to duly consider ways to increase the financial resources allocated for climate action” and calls upon developed country parties to “contribute to a robust eighth replenishment… to support developing countries in implementing the Convention…” The guidance note also specifically invites GEF “to duly consider the needs and priorities of developing country Parties when allocating resources to developing country Parties.”

In fact, the Memorandum of Understanding between COP and GEF explicitly states GEF policies, program priorities and eligibility criteria related to UNFCCC shall be decided by the COP.

“All developing countries, be it in Africa or Asia or Latin America are calling for an increase in overall GEF funding because there are legitimate needs for climate action and also other areas like biodiversity,” said Kamal Djemouai, an independent climate consultant from Algeria and former AGN chair. “We need new and additional finance for all areas from climate change to biodiversity to land management.”

The United States has pushed to keep current funding low, despite owing $102.4 million to the GEF for previous replenishment cycles.

The other issue is donor-dictated policies. Fakir explained that GEF policies, country allocations and focal area programming are dictated by developed country contributors that are donors to the trust. Djemouai agreed, saying allocations to the GEF “do not reflect the needs of developing countries or even the guidance given by COPs.”

GEF Chief Executive Officer and Chairperson Carlos Manuel Rodriguez declined to reply to this reporter’s questions.

The United States Disappoints

The other recent blow to expectations of increased climate finance delivery came last week when the United States allocated $1 billion toward international climate finance for fiscal year 2022. U.S. President Joe Biden had promised to deliver $11.4 billion each year by 2024.

“Hopes were raised quite high, but the allocation fell severely short. So yes, it is disappointing,” said Joe Thwaites, an associate of the Sustainable Finance Center at the World Resources Institute. He pointed out that, at this rate, it would take up to the year 2050 for the United States to meet its target of $11.4 billion per year unless the 2023 U.S. spending bill allocates substantially more toward international climate finance.

The United States also has not set aside money for the Green Climate Fund (GCF). GCF mobilizes funding to enable developing countries to adapt to a rapidly warming world. This comes as the United States still owes $2 billion to GCF out of U.S. President Barack Obama’s pledge of $3 billion.

An Unfair Advantage for Some Island Nations?

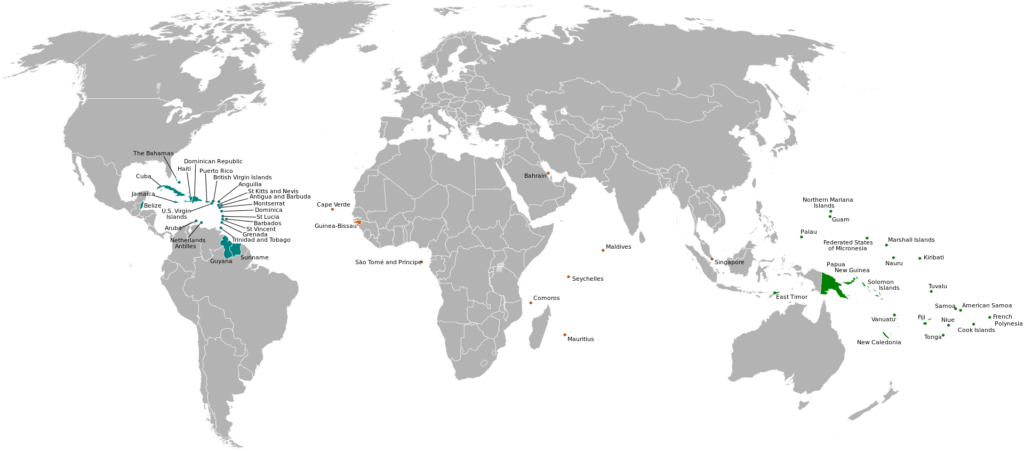

Policy recommendations from the February 2-4 GEF meeting suggest support for introducing a “Vulnerability Index” to replace the GDP index used as the criteria to access climate finance. This has given rise to concerns among certain developing countries that climate funding for poorer nations could instead go to richer ones.

On March 18, Brazil, India, Mexico, South Africa, China and Latin American countries released a joint statement raising concerns about the Vulnerability Index. The term “vulnerable countries” is not part of any multilateral environmental agreements for which GEF is the financing mechanism. Currently, the only categorization is “developed” and “developing.”

The GEF must “continue to treat all developing recipient countries equally and, in this regard, must not introduce new categories of countries or to provide for any differentiation or graduation among developing countries for accessing its financial resources or financial terms,” the statement argued.

This policy recommendation follows a previously made demand at UNGA to use a Multidimensional Vulnerability Index (MVI) for small island developing states (SIDS) to access concessional financing, or grant funding.

Small islands are vulnerable to climate change impacts. But it could be considered unfair to rank SIDS that are high-income or even upper-middle-income countries, like Mauritius and St. Lucia, higher than least developed countries, like Mozambique, Yemen and Afghanistan. A higher ranking would open the path to lower interest-rate loans.

The United Kingdom, too, favors reworking the criteria. Geopolitical considerations like accommodating Caribbean islands post-Brexit to offer the Commonwealth as an alternative to the European Union might play a role.

The GEF is holding another meeting for discussions on the eighth replenishment in the first week of April.

Rishika Pardikar is a freelance journalist in Bangalore, India. She had reported for Toward Freedom from COP26 in Glasgow.