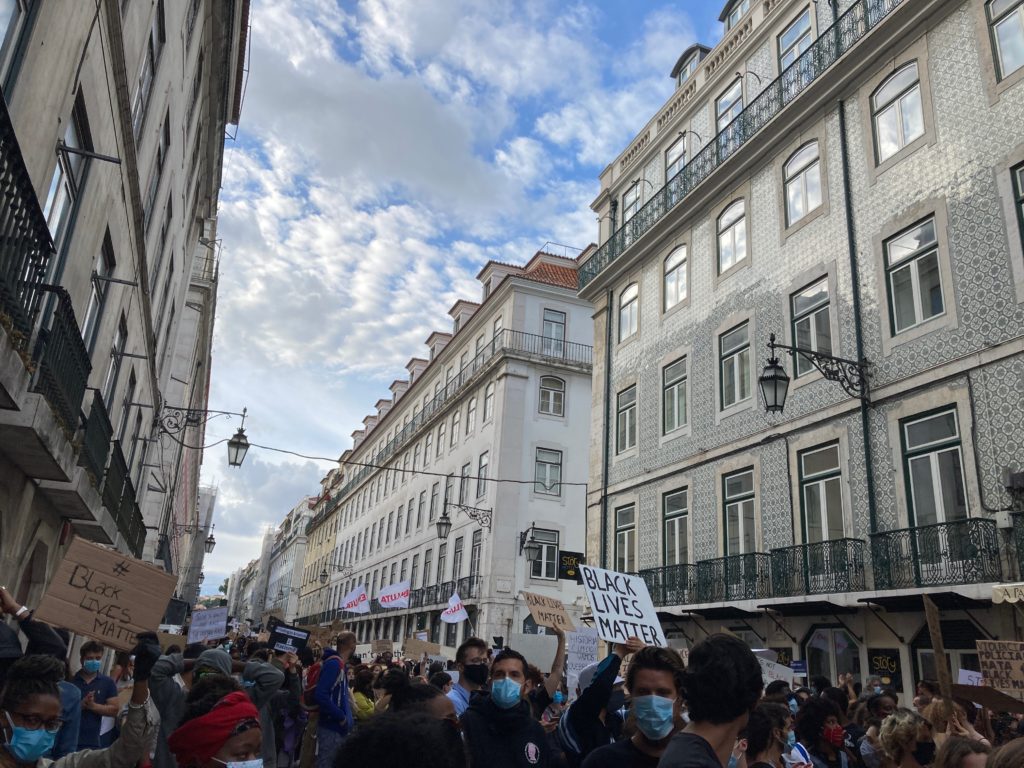

In the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd by a police officer in Minnesota, Black Lives Matter protests spread across the globe, and Portugal was no exception. In Lisbon, at least 20,000 people attended the largest anti-racism protest in decades, according to an estimate from the anti-racism organization SOS Racismo.

Signs and chants at the march explicitly used Black Lives Matter slogans as a demonstration of solidarity with the US movement for racial justice. However, there were also efforts to draw a connection to racism in Portugal.

“We did it to remind people that racism is not only in the United States, it’s also in the daily lives of people in Portugal, in structural ways in Portugal,” said Mamadou Ba, who is part of the leadership team of SOS Racismo, when we spoke on the phone several weeks after the march.

This common cause was evident at the march. Alongside cardboard signs that read “Black Lives Matter” and others that listed the names of dozens of Black Americans who have died at the hands of the police over the last decade, as well as a banner that said “I can’t breathe: Out with Trump,” other signs at the June march referred to Portugal’s history in the slave trade and current issues. One read, “Slave ships no longer exist, but your silence enslaves.” Another said simply: “Portugal is racist, too.”

Protestors carried signs with the names of victims of racist violence in Portugal as well. Some of the more well-known cases include the killing of Alcindo Monteiro, a 27-year-old immigrant from Cape Verde by white supremacists in Lisbon in 1995, and the beating death last year of Luís Giovani, a Black immigrant to Portugal.

Buki Fadipe, a British citizen living in Lisbon, said that, for her, going to the march was about standing against racism everywhere.

“It’s pretty obvious being a Black woman, a Black British woman, obviously my motivations were to show solidarity and to stand up for this cause, because racism isn’t just specifically happening–even though the focus, the movement started–in the U.S., it’s a global situation. And I myself have been a victim of racism in many different countries around the globe, including in the one I’m living in currently,” she said in a phone interview a few weeks after the march. “I would have attended a march in whichever country I was in.”

Cristina Correia Almeida said it was her first march. She was born in Portugal to parents from Cape Verde, and only naturalized as a Portuguese citizen at age 20, because Portuguese law does not guarantee birthright citizenship.

“What motivated me to go was that I saw that nothing had changed,” she said. “I thought that this situation with the virus would change how people thought, but nothing changed.”

The marchers wound their way from the Alameda fountain through neighborhoods with populations of immigrants from Southeast Asia and Africa. Residents stood on their balconies waving and chanting as the protesters walked by.

Portugal has a diverse population, with immigrants from former Portuguese colonies in Brazil and several African countries, as well as descendants from generations of immigrants from those places, although the country does not keep statistics on race. There are statistics on immigrants, who in 2020 amounted to nearly 500,000 residents in a country of 10 million. The march drew participants from several different immigrant communities who have a direct relationship with Portugal’s colonial past, including Brazil, Angola, Mozambique, and Cape Verde.

Ba said that it was important for racial minorities in Portugal to see a march of that size, and with support and participation by people of “every color, every age, every social class.” He said he saw it as evidence of a change in the collective consciousness, pointing to the number of young people at the march as an indication of the changing mentality.

Almeida said she cried at the march, “out of happiness, but also out of sadness for the situation we’re in.”

Fadipe found the march meaningful for the connections people made from a global issue to their local context. “I am getting the impression that the reasons for people showing out weren’t just marching for Breonna Taylor or George Floyd or whatever, they were there out on the streets marching for either themselves, their friends, their family,” she said. “#BlackLivesMatter is this movement that started in the U.S., but the premise is it’s against racism, full stop, not just racism in the U.S. So I think and I hope that in all the European countries, people did exactly the same thing: they made it relevant to themselves, relevant to their city or whatever.”

Telma Tvon, a writer, social worker and member of the hiphop community, was enthusiastic about the turnout.

“I was really happy, and I hope it’s something that will last,” she said. “I think a lot of people there were at a protest for the first time. I think a lot were motivated by what they saw, what happened to George Floyd. But afterwards, I started to think, ‘how is it that the life of a Black American is valued so much here and our lives aren’t valued like that?’”

Carlos Dias, a real estate consultant and activist, echoed Tvon’s uneasiness with the show of support for Black Americans who are victims of racial violence, while little attention is given to Black people in Portugal who suffer similar treatment.

“We have George Floyds. We have Breonna Taylors. We have Ahmaud Auberys. We have Tamir Rices,” said Dias. “But we don’t talk about it here.”

He cited the murder of Giovani, a 21-year-old from Cape Verde who was attacked last December in the Portuguese city of Bragança by a group who used a belt and brass knuckles to beat him; Giovani died in the hospital 10 days later. Although authorities officially determined that race was not a motive in the killing, activists in Lisbon organized a march to condemn the murder.

Dias was born in Portugal and struggles with the racism he has often experienced. He compared racism to one of the most iconic and traditional foods in Portugal. “I usually say racism is like the sardines,” he said. “There are a lot of people who say, ‘oh I don’t like it, but I sure love that smell.’”

Participants at the Lisbon march came from other countries not directly tied to Portugal’s colonial exploits, including US and other European citizens living in Portugal, who, like Fadipe, were eager to show support for the movement.

“I wanted to go because I didn’t have access to being in America and I very much believe in the movement. It was the first time in my life that I felt like I had to be there,” said Tara Goulet, a white American living in Portugal. “My original intention was to go to the U.S. Embassy protest… I really wanted to be waving a poster in front of the U.S. Embassy.”

For Goulet, marching in Lisbon was about showing support for the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, but also acknowledging that there is racism in Portugal. It also prompted her to begin doing more research, in particular about the country she’s currently living in, a process she says has been eye-opening.

“To find out that you’re in a place that started the slave trade was really hard to swallow,” she said.

Like many European countries, Portugal has a sordid history when it comes to race. It was the first country to bring slaves from Africa to Europe. As a colonial power, Portuguese explorers invaded and exploited land all over the world, enslaving African people and selling them across the Atlantic to Brazil and the United States.

Ba said that the shared origin of colonization and the enslavement of African people is the reason racism is similar in Portugal and the United States.

“I really want it to get better. I am hopeful,” said Almeida. “If education doesn’t change, nothing is going to change.”

Dias thinks a lot of Americans are not familiar with Europe’s troubled history. “I understand that Americans, you have to look at your own country and the problems that you have, but they don’t know how the Portuguese, Spanish, French, Dutch, and Brits actually influenced a lot of the ways that they see race,” he said. “A lot of the ways that they created the slave trade…The Portuguese were there 150 years prior to everyone else.”

In Portugal, Ba, Almeida, and others pointed to the education system as a major part of the problem.

“The dominant academic and public discourse in Portugal still denies the existence of racism in the country,” said sociologist Cecília MacDowell Santos, who teaches Brazilian culture and society at the University of San Francisco and is a research member of the Center for Social Studies at the University of Coimbra in Portugal.

There is a common myth in Portugal that the country was a more “gentle” or “good” colonizer –as compared to, say, the Dutch or the English, who were presumably worse or more cruel to people in the countries they colonized. This idea, known as Lusotropicalism, suggests that Portuguese colonizers were better by comparison, largely because of intermarriage between colonizers and local populations.

The myth of the Portuguese as “gentle” colonizers is evident in the work of several Portuguese scholars dating from the 1950s, although it originates in the work of Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre, who is known as the father of Lusotropicalism. In the 1930s Freyre suggested that the Brazilians and the Portuguese benefitted from miscegenation, or mixing between races. This idea came back to Portugal and was used to cast a more positive light on Portuguese colonialism.

“Gilberto Freyre’s work was incorporated into this ideology of racial democracy, which was imported from Brazil to Portugal and also other Portuguese colonies, to deny the existence of racism,” said MacDowell Santos. “He also uses ‘racial democracy,’ as if Portuguese colonialism did not establish racial separation and hierarchies and inequalities and violence.”

In the 1970s, Lusotropicalism was used to justify keeping Portuguese colonies, insisting that the country had been multicultural, multiracial and multi-continental, and that losing the colonies would mean an end to the Portuguese State. Nonetheless, in 1975, following more than a decade of war with its former colonies, several African states that had been colonized by Portugal declared independence: Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, Guinea Bissau, and São Tomé and Príncipe.

Even so, the Portuguese narrative of the soft colonizer persisted, and it has maintained a place in the national identity. This is something that protesters and educators are working hard to change.

Today, some in Portugal are caught between celebrating their national heroes–in their case, explorers who sailed across the Atlantic and “discovered” new lands–and reckoning with the violent and exploitative practices that made those voyages so profitable.

Unlike in the United States, there is not a public conversation about removing statues that celebrate the so-called “discoverers,” nor have such statues been removed or defaced. The Monument of the Discoveries in Lisbon, on the banks of the Tagus River, celebrates the Portuguese Age of Discovery with profiles of more than 30 Portuguese national figures, including Vasco da Gama, Ferdinand Magellan, and Bartolomeu Dias.

“I don’t have a problem with the statues themselves. I know history enough to see what they have done,” said Dias. “My problem is the mentality.”

Dias thinks that many Portuguese people ignore racism in their history and their present because it’s too difficult to address. “If you admit you have racism, you have to take care of that,” he said.

Seven weeks after Lisbon’s Black Lives Matter march, on July 25, actor Bruno Candé Marques, who is Black, was shot to death in the outskirts of Lisbon while walking his dog. The actor’s family and witnesses told Portuguese newspapers that the shooter had yelled racial slurs and threatened Candé a few days before the shooting. In a press release, SOS Racismo called it a racially motivated murder.

There was a weekend of protest after Candé was killed, all across Portugal, from Lisbon to Porto in the north, and several smaller cities in between. Although the demonstrations were smaller than the Black Lives Matter march in June, Dias found them reassuring in some sense –an indication that people in Portugal were willing to march against racism in their own country.

The day after the marches for Candé, the nationalist conservative political party CHEGA! (roughly translated as “Enough!”) held a march in Lisbon to proclaim, “Portugal is not racist.” The CHEGA! party was formed in 2019 and won a single seat in the Portuguese legislature that year. The party has been accused of having ties with neo-Nazis and the party’s leader complains about racism being blamed too often and flatly states that there is no structural racism in Portugal. But the CHEGA! march was only attended by a few hundred people, according to local newspapers.

Marches aside, the anti-racism work of SOS Racismo and other activists was going on before this summer, and will continue. They are working to change the laws around nationality for those born in Portugal, to criminalize racism, to decolonize the public school curricula and the national narrative, and to pressure the government to understand the dimensions of the racial discrimination issue in Portugal. Their work has been bolstered by an increase in support from offers to help from individuals, companies, and artists.

“It’s good news,” Ba said. “We’ve never had as much interest as we have now.” Some of that interest has come from the wrong people, however, as in early August, Ba and several other prominent Black activists and politicians were sent a threatening email telling them to leave the country within 48 hours.

Nonetheless, many activists and others see cause for hope in the growing movement.

“By the amount of young folks I saw at that march, I definitely feel there’s hope for Portugal to head in the right direction,” said British activist Fadipe. “What I would have liked to have seen, I felt like I recognized, there were a lot of Black Portuguese, but I wanted to see more of the white middle-class Portuguese.”

Author Bio:

Jessica Roberts is an assistant professor of communication at the Universidade Católica Portuguesa. She is co-author of the 2018 book, American journalism and “fake news”: Examining the facts.