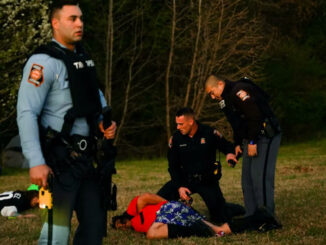

Ashley O’Shay’s documentary “Unapologetic” is an examination of the lives of Black women and queer activists in Chicago as they navigate the response in the streets to the police killings of Rekia Boyd in 2012 and Laquan McDonald in 2014. While the documentary provides a chilling revelation of just how long the process for “justice” for these two police killings took, it also, and perhaps more importantly, focuses on the struggles on multiple levels that the people who took to the streets and organized behind the scenes to demand that justice endured during that time. Two of those people are Janea Bonsu, an organizer with Black Youth Project 100 (BYP100), and Ambrell “Bella” Gambrell, a scholar and raptivist (a rapper who is involved in political or social activism).

After an introductory soliloquy in which viewers are let in on the meaning behind the film’s title, footage appears from a direct action in what looks to be a ritzy eatery in one of Chicago’s whiter areas. Agitators—and I use that term quite intentionally and with the utmost respect—interrupt the relaxed regular dining of the mostly white patrons with a coordinated call and response, indicting the dismissal of the suffering of poor Black families struggling to put food on their tables, who were probably not far from where the visibly uncomfortable white folks were sitting. They all sat there and chit-chatted over meals that were probably overpriced.

Though some of the patrons tried to appear patient and listen attentively, many more tried even harder to ignore the agitators and get on with their meal despite them, which is the perfect representation of the way much of white U.S. society responds to Black suffering and death in general. But the comments of the testy restaurant employee, dressed in what appears to be an elf costume—which makes his testiness all the more comical and infuriating—really bring home the point that the documentary endeavors to make, but also the point that the agitators were making.

The documentary proceeds to follow Janae as she completes her doctoral dissertation while organizing with BYP100, and Ambrelle as she uses her talent as a rapper and her exposure to the criminal justice system through family incarceration as the foundation of her activism. One should not mistake the difference in these two women being one of class—both are residents of the Southside of Chicago, and both have attended and graduated college. The difference appears to be the paths each takes with that foundation that the documentary shows contributes to their organizing efforts in different ways. One pursuing a Ph.D. based on pursuing alternatives to the disastrous impact on Black women that social services and interactions with the police have. The other eschews pursuit of further education in the system that she excoriates in one of her poems recited at an early protest.

And this is one contradiction that the documentary raises, or should raise, among its audience regarding academia and organizing—how useful is academia in organizing? Because while Janae is clearly passionate about working to find solutions to the very real problems of the negative impacts of the social services system on Black women, can solutions be found inside the very systems that perpetuate those problems? There are already plenty of educated folks in the social work field and even in policing, many of them Black. When we see in the documentary how Janae’s doctoral chair counsels her that she doesn’t have to talk about everything in her dissertation, isn’t this a reflection of how the established institutions respond to Black people when we raise the alarms about that system and its impact on us? A question to ponder, but not with the aim of besmirching Janae’s pursuit of her Ph.D., because the contradiction isn’t one regarding personal choice, but it is about systemic realities and being realistic about them.

Conversely, rather than go the academic route, Ambrelle took to the streets in the pursuit of organizing her own space, especially on behalf of Black women—and particularly queer women—who have experienced victimization by the carceral state. Clearly a skilled wordsmith and masterful with rap technique, she also draws upon her own experiences with multiple generations of family exposure to incarceration, using the experience of her mother’s incarceration and then her brother—still incarcerated at the time of the making of the documentary—to help other Black women deal with the trauma of that systemic victimization.

Both women actually have experience with the carceral system impacting their families, and both connect the repression of the state as part of the “War on Drugs” to the ongoing war on Black and poor people, and how this repression destroyed the stability of even economically struggling Black communities like in the Southside of Chicago.

That both women highlight the need to elevate the voices of young, Black and queer women in the new efforts at organizing is a central theme in the documentary. The role women play in organizing—that has been too often overlooked throughout the historical reflection of the long fight for liberation for Black people—is an important and well-highlighted discussion that both women and others throughout the documentary raise. In organizing meetings and in the streets, the documentary points out several instances throughout when Black men literally take the mic from Black women while they were speaking or talk over them, thereby dominating the discussion. It seems the film focuses on the organizing that occurred after Rekia Boyd’s killing precisely because few outside of Chicago probably understood how much focus the people in the streets DID pay to her killing, despite people outside of Chicago saying that the movement writ large doesn’t pay much attention to Black women killed by police.

However, there are contradictions even in these discussions in the film, as Ambrelle particularly describes Black men as being only interested in their position to power and as oppressors of Black women. But even with this troubling discourse about Black men, other voices in the documentary point out other possibilities, chief among them that Black men who exhibit misogynistic behavior toward Black women are largely unconscious of how some of their behavior negatively impacts Black women because they, too, are oppressed and do not realize the depth of their oppression. Just as in the questions surrounding the utility of academia in the movement, raising this contradiction is not a dig on Ambrelle, but an occasion to examine how we all talk about Black men in the spaces we all occupy in the movement.

Those contradictions that we all must wrestle with aside, the documentary delves into the hectic, exhausting, emotionally taxing life of Black organizers, activists and agitators—whatever you want to call them. The work that is done to confront city councils that refuse to listen to the demands of the people most impacted by police violence that is literally funded by their tax dollars, the difficulty balancing organizing and personal lives, the importance of strong family ties and support, and the difficulties even pursuing romantic interests are all issues among several others that remind the viewer that organizing is not a hobby. Nor is it a lifestyle. It is—for many of us—our life, our whole life. And it is such because our lives depend on it. But as the two women show in the various ways that they stay connected and grounded when they are not organizing or agitating, the necessity of having those connections and making that time for them outside of organizing and agitating is critical to their survival, too.

The documentary also presents a detailed timeline of the response of the Chicago Police Oversight Board and the mayor’s office to the police killings of Boyd and McDonald. In that timeline, we see the way now-Mayor Lori Lightfoot conducted herself in the presence of these agitators as they demanded the cop who killed Rekia be fired, but also the cold detachment as Rekia’s brother testified before the Chicago Police Board that Lightfoot presided over as president.

Watching it, you wonder how in the hell did she get away with presenting herself as a progressive after the despicable way in which she responded to these incidents and the people in that community demanding action be taken against the cops who committed them. Lightfoot’s recorded comments from that time period, and those of Rahm Emanuel, are repulsive and one wonders how the hell Lightfoot was elected mayor after the revelations of her boss Rahm Emanuel’s attempts to cover up evidence of the McDonald killing and the corruption of the Chicago District Attorney’s Office that was connected to Emanuel’s shady dealings. The politics of identity divorced from class analysis and good ol’ Democratic lesser-evilism are at play here, but it is not pointed out in the documentary. That is unfortunate, because these issues are critical drivers behind continued political malaise and stagnation among the very community the agitators are agitating on behalf of.

“Unapologetic” is a much-needed exposé into the actual lives of actual activists. It reveals that the “people in the streets” are ordinary folks struggling with ordinary life, but they also have the extraordinary desire to challenge and change this system because, as Black women and Black queer people, they also struggle with the extraordinary burdens heaped upon them by this society. That seems to be the primary focus of the documentary, though it also looks at how those ordinary people are pushed to be unapologetic about their activism and agitation—and that is a good thing. However, it leaves out the deeper discussions we need to have about the gender relations between Black men and Black women, classism, and identity reductionism that exist within this important work, all of which we cannot afford to ignore if we ever want to be healthy enough—mentally, emotionally, and as a community—to endure this continued struggle.

Jacqueline Luqman is a radical activist based in Washington, D.C.; as well as co-founder of Luqman Nation, an independent Black media outlet that can be found on YouTube (here and here) and on Facebook; and co-host of Radio Sputnik’s “By Any Means Necessary.”