Editor’s Note: This review contains spoilers.

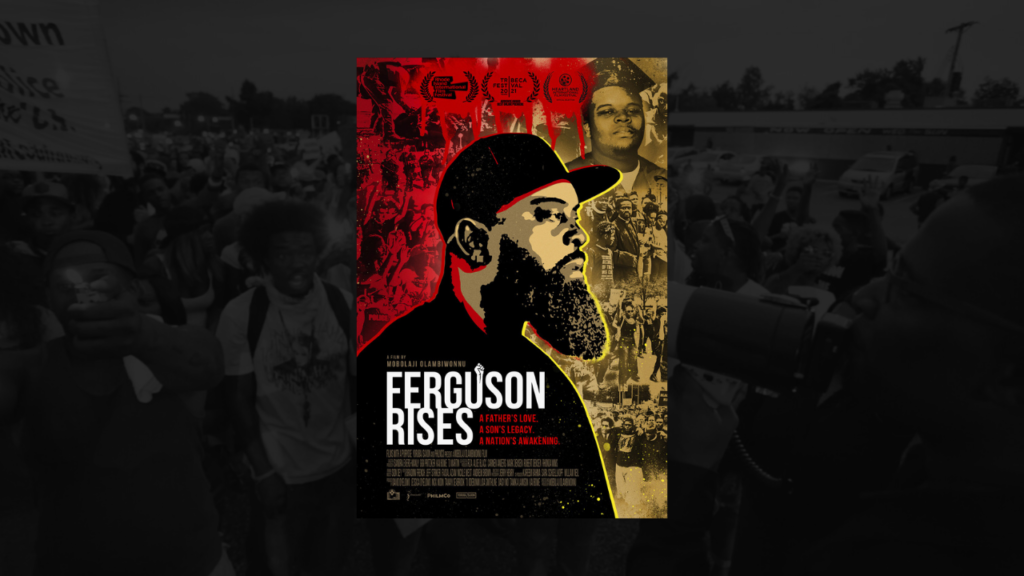

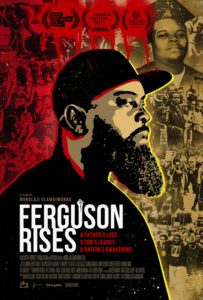

The documentary, “Ferguson Rises,” produced by Mobolaji Olambiwonnu and Films With A Purpose studios, is an important examination of how a global movement, Black Lives Matter, was sparked.

The opening scenes of happy, playing, gleeful children, mommies and daddies, and families doing what families do… abruptly cuts to a black screen and the sound of the shots that ended Michael Brown, Jr.’s life on August 9, 2014, in Ferguson, Missouri. From there, the documentary goes on to provide important details about the growing unrest in the small, predominantly Black community that led to the Black Lives Matter movement.

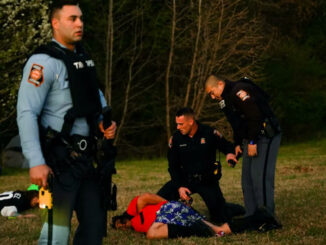

The film examines how Ferguson police called for backup from 15 police departments in the Saint Louis area to deal with a crowd that had formed after police had left Brown’s body uncovered and decomposing in the sweltering heat for more than four hours. They did that faster than how long they took to call a coroner to cover the 18-year-old’s body.

The filmmaker also casts a lens on Ferguson’s smallness. The city has just 20,000 residents and is almost 70 percent Black. It is so small that Michael Brown, Sr., knew some of the police officers on the scene and went to high school with them. Yet, they ignored him when he asked if the person lying dead in the street was his son. Michael Brown, Jr.’s mother, Lezly McSpadden, not only was ignored when she arrived on the scene—she was callously disrespected.

Whether Brown stole cigars in a convenience store as well as whether he had his hands up when police officer Darren Wilson encountered him are accurately contextualized in the documentary. The film sheds light on the then-police chief, Tom Jackson, repeatedly stating to the media Wilson was not aware of Brown’s possible involvement in the incident at the convenience store. This, of course, would call into question what reason Wilson had to stop Brown. Jackson went on to change his story.

The irresponsibility, sensationalism and outright dishonesty of the media is on full display in the documentary. In one clip from CBS This Morning, the lower-third graphic on the screen read, “Missouri Riots,” but the footage showed Brown’s mother and neighbors crying and emotional at the scene of his shooting. No footage of actual riots.

In chronicling the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement, the documentary provides key moments in that timeline that were known only to the residents of Ferguson. They begin with an elder U.S. Army veteran walking the streets of Ferguson the day after the shooting, waving a U.S. flag, reciting with emotion the words to the spiritual song, “Oh Freedom.”

Extensive coverage of eight hours of protests shown in the documentary were uneventful. That is, until Ferguson police brought in riot gear and military equipment to assault residents because, as one man in the film commented, police wanted to stop them from marching to the police station. Yet, CNN and other media outlets throughout the country falsely conveyed the first night of protests was violent because of residents’ actions.

The reality of two Fergusons—one Black and one white—is well conveyed in the documentary. Several white residents appeared to dismiss the anger of Black residents, with one white man reducing the protests to “tantrums.” Their cluelessness continued with comments about how the “community has been portrayed to the outside world” and how “the phrase ‘Black lives matter’ doesn’t sit well with a lot of white people” because “all lives matter.” The willful obtuseness is enraging, but this is the reality of how our struggle is viewed.

Yet, a few white residents recognized the centuries-long rift in Missouri that led to that horrible day in Ferguson. The white pastor of the African Methodist Episcopal church sees the protests as a spiritual battle between heaven and hell, good and evil. A former Ferguson police detective recognizes the racism in the police force, even though he excuses cops using tear gas on protesters. Then we hear from a white resident who was going to move out of town until he drove by the scene of Brown’s murder and realized just how horrible the murder of the young man was and how traumatizing it must have been for the embattled community to have to see Brown’s body decomposing in the street.

The documentary focuses on Michael Brown, Sr., and the trauma men endure when their children are killed. It also takes a look at residents’ clarity on the systemic nature of what they’re fighting against. They understand it is not about individual police officers or a few bad apples.

The end scenes, however, are a study in contradictions, with Cori Bush going from being a Black grassroots activist in Ferguson to an elected representative in the U.S. Congress. Meanwhile, a Black man named Wesley Bell was sworn in as Saint Louis prosecutor, but did not prosecute Wilson. Ferguson elected its first Black mayor six years after Brown’s murder, but the Time magazine cover featuring Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi and Patrisse Cullours as the faces of Black Lives Matter did not age well considering the enormous financial scandal that fractured the movement. Clips show Los Angeles and New York police departments announcing budget cuts. Yet, those cuts were miniscule compared to the total budgets of those police forces. Plus, claims of rising crime have fueled the rallying cry to “refund the police,” even though they were never “defunded.” Meanwhile, positive clips of Georgia politician Stacey Abrams and U.S. Vice President Kamala “The Cop” Harris, seem out of place for a documentary that for the most part condemns the system.

“Ferguson Rises” is a very good documentary. But the triumphant and hopeful end scenes are a sobering reminder that mere representation without radical or justice-focused politics often replicates the system.

Jacqueline Luqman is a radical activist based in Washington, D.C.; as well as co-founder of Luqman Nation, an independent Black media outlet that can be found on YouTube (here and here) and on Facebook; and co-host of Radio Sputnik’s “By Any Means Necessary.”