By Lesley Becker

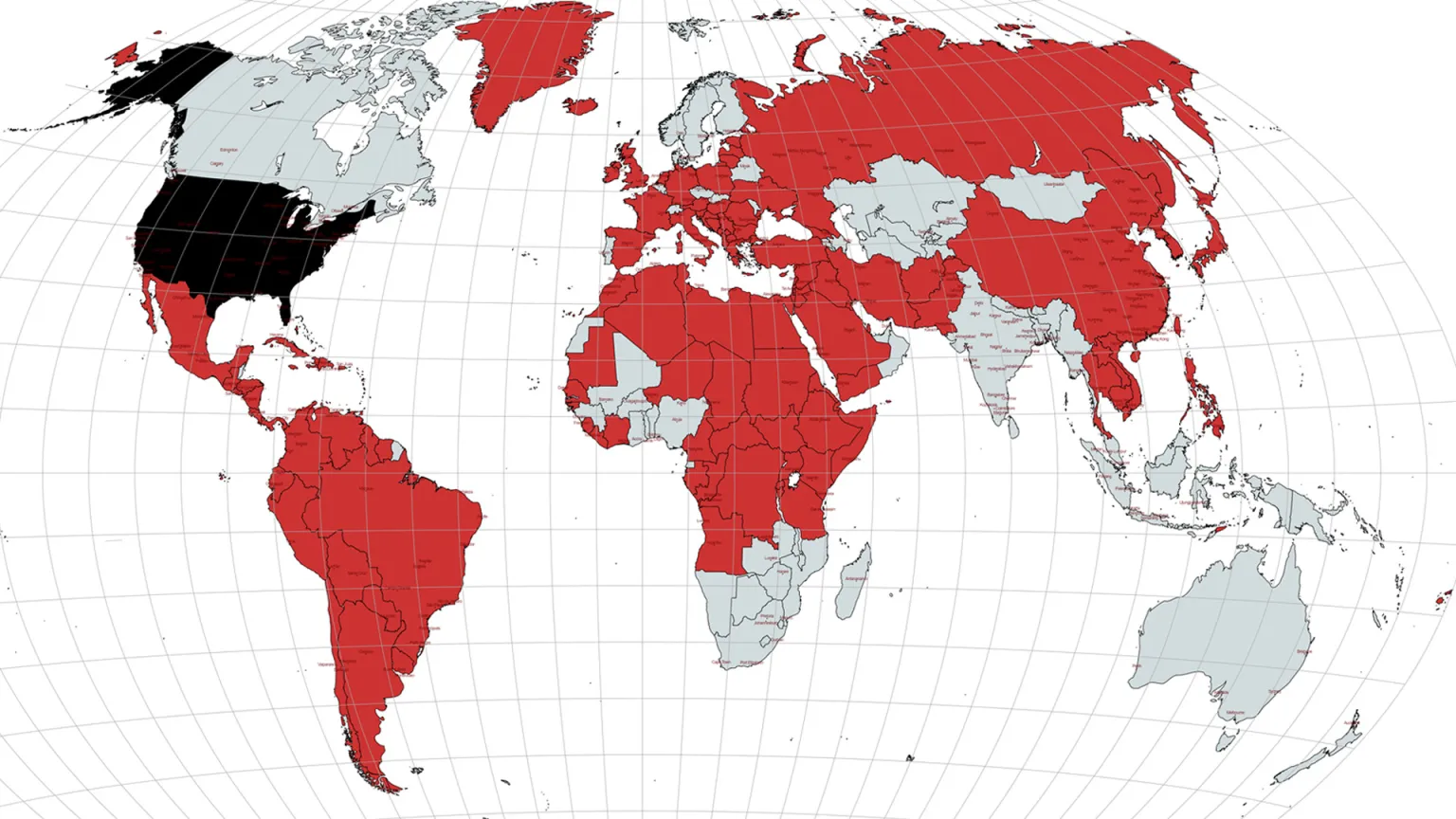

Activism and Art are a potent combination for addressing problems that are both enduring and unendurable. The play, Eclipsed, transports the audience into the intimate dwelling of women struggling to survive while living as sexual slaves in a rebel forces encampment at the end of the Liberian civil war in 2003. The story follows a 15-year-old African girl as she escapes from the encampment to become a child soldier in the rebel forces.

Written by Zimbabwean-American playwright Danai Gurira, Eclipsed made history by being the first Broadway show with an all-female cast, and the first all African-American cast, and an all-female creative team. Eclipsed was on Broadway in 2016, with Oscar winner Lupita Nyong’o in the lead role.

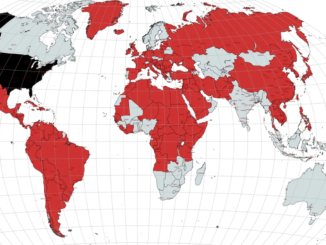

The playwright wants to create awareness about injustices encountered by girls and women around the world by the stories in her plays. “Narrative is in my toolbox, and what I find powerful about narrative is that it actually allows people to be connected, to be disarmed, to see other people across the world that they might perceive of as statistics, [rather than] as actual fellow people that they care about and that they want to see freed to live self-determined lives,” she said in an interview.

Gurira’s work transcends the rationalizations created by terms such as “rape as a weapon of war” that are used to characterize the human experience of sexual violation and violence. Her work portrays the humanity of the captive women, and the difficult choices they must make during a time of war, and how the trauma of those experiences, particularly rape, changes them.

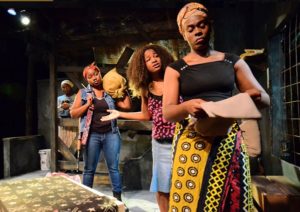

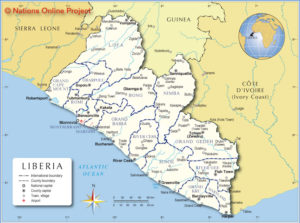

Why is Eclipsed relevant now? In September of 2020, President George Weah of Liberia declared rape a national emergency following a three day protest in the capital city of Monrovia. There were 5,000 anti-rape protesters, and there were violent clashes with authorities. Police tear-gassed thousands of anti-rape protesters. It is difficult to collect meaningful statistics as to the rate of rape in Liberia. A World Health Organization report estimated 75% of women in Liberia at the end of the civil war had experienced rape. That statistic was challenged by American writers because, they wrote, it seems like an improbably high rate. However, the current situation in Liberia, where Covid-19 restrictions have increased the number of Sex and Gender-based attacks by fifty percent, is compared to the same high rate of attacks during the Liberian civil war (1999-2003)

which is the setting of Eclipsed.

The impetus for writing the play came from a 2003 photo appearing in the Western press of Liberian women fighters. Gurira was struck by their attractive appearance, the fierce and intense look in their eyes, and by their guns and their stylish fighting gear. In 2003, the Wall Street Journal interviewed a 20-year-old fighter calle1d Black Diamond, and described her appearance in an almost romantic way: “A pistol and a cellular phone hung from her trendy, wide leather belt. Her jeans were embroidered with roses. Her fellow guerrillas were equally fashionable, wearing tight-fitting jeans, leopard-print blouses and an assortment of jewelry. The number of women in her unit, she said, is a military secret.”

Gurira traveled to Liberia in 2007, setting off on a journey that would reveal that the intensity of the young women fighters in the photo was not empowerment, or a fierce loyalty to the rebel forces and brotherly rebel male fighters. Instead, the style and swagger of the young women covered over the deep trauma of having lived through unspeakable horrors during the civil war including being gang-raped, watching family members murdered, their homes looted and mothers and sisters raped by soldiers. Gurira interviewed thirty women including former women soldiers and women in the Peace Movement who are credited with forcing an end to the Civil War. The characters in the play reflect the histories of those women, as well as Gurira’s research, including the award winning. documentary Pray the Devil Back to Hell and the Human Rights Watch report “Roles and Responsibilities of Child Soldiers”.

Gurira weaves together a story that brings the audience into the women’s lives, using experiences that we can identify within our own lives. The women fuss about their hair, clothing and what will there be for dinner, even as they hide the fifteen-year-old girl from their abuser, the Commanding Officer. The fifteen-year-old, who is called “The Girl,” arrives at the camp as a bright, energetic child, able to read, and having plans to go to school to become a doctor or constitutional lawyer.

The commander, called the “CO” by the women, attacks The Girl when she goes outside to go to the bathroom, then designates her as the “number four” wife. After The Girl is raped by the CO, she returns to the shed where the Wives live together. She is listless and unresponsive to questions from the women about what happened, except to say the CO “did it” to her. Soon after, the CO arrives at the women’s shed, and with dread and anxiety they must line up for him, as he chooses which woman he will take away next.

The women in the play go by their ranking as “Wives,” a system set by the CO, and they do not use each other’s names, but address each other with their number in the ranking. Wife Number One, the eldest wife, was captured when she was twelve, and has been held captive for ten years. Number Two was ousted from the women’s shed and has become a rebel fighter. Number Three is six months pregnant with the CO’s child.

After the CO’s officers loot a village, he gives clothing and other items to Wife Number One, and she finds a book about Bill Clinton. The Girl reads parts of it to some of the other Wives, and their struggle to make sense of Clinton’s troubles provides some comic relief to an otherwise intense and harrowing play.

Wife Number Three calls Monica Lewinsky,“Wife Number Two,” and the woman express wonder at the U.S. Congress trying to remove Clinton as president for having two wives. They remark on the closeness they feel as Liberians to the United States, since it was the United States that set up the founding of their country.

Wife Number Two returns to visit the women’s shed, carrying a large gun and dressed in jeans and a slinky top. She has brought food for the Wives, offering a bag of rice because they have none. Wife Number One has moral authority, and will not accept the food, because Number Two is involved in war atrocities. Number Three, pregnant and bemoaning the shortage of food, wants to accept the rice. The apparent freedom that Number Two has as a soldier appeals to The Girl.

Number Two entices The Girl to become a soldier so that she can get a gun and protect herself from being raped. The Girl follows Number Two and becomes a child soldier. She finds she is required to participate in looting, killing and (much to her dismay) rounding up girls from the ransacked villages to bring to soldiers to be raped.

A woman from the Liberian Woman’s Peace movement secretively visits the Wives to tell them that the war will be ending soon. The unendurable trauma of their war experience has unraveled the Wives’ identities, and they struggle to remember what their names were before the war. Rita, the Peace Woman, coaxes Number One to remember. Finally, she whispers her name, and Rita writes “Helena” in the dirt of the shed floor. The educated and upper-class Peace Woman, Rita, has her own story. Her daughter has disappeared, and she searches the rebel camps in hopes of finding her. Gurira lays bare Rita’s struggle with her classism when Rita airs the complaints of the Peace Women to Helena, saying that the CO is “trying to treat us like we’re village girls they rob from the bush,” without awareness that Helena herself was a 12-year-old girl running from an attack on her family’s home in a village, and captured when she was hiding in the bush.

The play ends when Charles Taylor leaves Liberia, signaling the winding down of the long civil war. The Girl has to choose whether to give up her gun in order to go with the Peace Women group; or to keep her gun and go back to the camp of rebel fighters. Helena (Number One) struggles with her decision to leave at first because her identity is her rank in the camp. Number Two cannot believe that she will be safe if she gives up her gun, and she returns to the rebel fighters’ camp. Number Three has her baby, and she chooses to stay with the C.O., believing that he will take care of her and her baby girl. She named the girl Clintine, after Bill Clinton. The naming of this Liberian child, begotten by rape at a rebel commanders’ camp during wartime, may symbolize Liberia’s call for support from their parent country.

Liberia was founded by the American Colonization Society in the early 1800’s as the first free country in Africa, as part of the “Back to Africa” movement designed by U.S. government to avoid abolishing slavery. For many years, U.S. involvement in Liberia was significant, especially in the exploitation of resources (rubber, diamonds and gold) by the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company starting in the 1920’s. The U.S. supported the violent and repressive government of Samuel Doe (1980-1990) but has been gradually but continuously disengaging since the end of the Cold War. In 1990, at the beginning of the brutal, 14 year Liberian Civil War, the U.S. citizens were evacuated and U.S. involvement, for practical purposes, ended.

The commanders in the Civil War illegally, according to the Geneva Convention, used over 15,000 children under the age of 18 as soldiers in fighting in Liberia between 2000 and 2002. Many people question U.S. disengagement with Liberia, a country considered to be the “stepchild” of the United States. One U.S. expert says that Liberia sees itself as the 51st state. However, while there are significant straightforward needs in Liberia now, such as DNA machines used to determine the perpetrator of a rape and technicians who know how to operate them, there are questions as to why the U.S. has continued to be unresponsive to Liberia’s crisis.

Despite declaring rape to be a national emergency last September, President Weah has not followed through with establishing a special prosecutor for rape, or setting up a national sex offender registry, or establishing Criminal Court E for hearing rape cases across the 15 counties in Liberia. In March of 2021, President Weah unveiled a DNA testing machine to be used to aid prosecution of rape cases. However, media reports indicate that there are no trained technicians who know how to operate the machine in Liberia.

In Our Bodies, Their Battlefields, Christine Lamb writes that rape is the cheapest weapon known to man.” And also one of the oldest, as some scholars analyze the Book of Deuteronomy’s “Law of the Beautiful Captive Woman” to support a view that women may be treated as “spoils of war”. There were many wartime atrocities, but in particular, the weaponizing of raping women and children leaves a lasting imprint on the cultural integrity of a society. The society in Liberia after the war has been called a “culture of impunity” where there is no penalty for attacking women and children.

Danai Gurira founded a website, newsletter and blog called Love Our Girls which raises awareness about girls in African who are abused and forgotten. She writes there:

“As a writer, scripting narratives is my act of resistance, my way of bringing that unheard African female voice front and center and allowing it to manifest its astounding value. I have always had a passion for women and girls, a hope to see them function on the same playing field as men and have the same opportunities and appropriate protections. I want to be more than an actress and storyteller but an advocate for women, not only in underdeveloped countries but all over the world.”

The play’s central theme is that the light inside of each of these women, a light that can be seen clearly in The Girl when she first arrives at the camp, is eclipsed by the trauma of rape and captivity. For the women who become fighters, this is compounded by the horror of the acts of war they witness and participate in.

Eclipsed is about how the light within these women was blocked by the reign of terror of the warlords, their soldiers, and soldiers of the government.

It is an open question as the curtain comes down: what will become of these girls and women when the war has ended? And it is an open question as well: what will it take, locally and globally, to repair the shattered norms that allow rape of children and women to be happening at alarming rates, and to muster the political will to prosecute and convict those who commit those crimes? Gurira uplifts the stories of women and girls in war and invites audiences to see the lives of women and girls who are subjected to repetitive rape, deprivation of food and freedom, by not showing them as “flailing victims” but instead “… these are dynamic women and girls, in the most treacherous of circumstances, and I want the audience to feel at home with them.” The play provokes the empathy that is necessary for social justice.

Lesley Becker is a playwright and director living in Vermont and a Reparative Board member at the Burlington Community Justice Center. Her plays are available to read on New Play Exchange; she is a member of the Dramatist Guild.