All of Haitian society is in revolt.

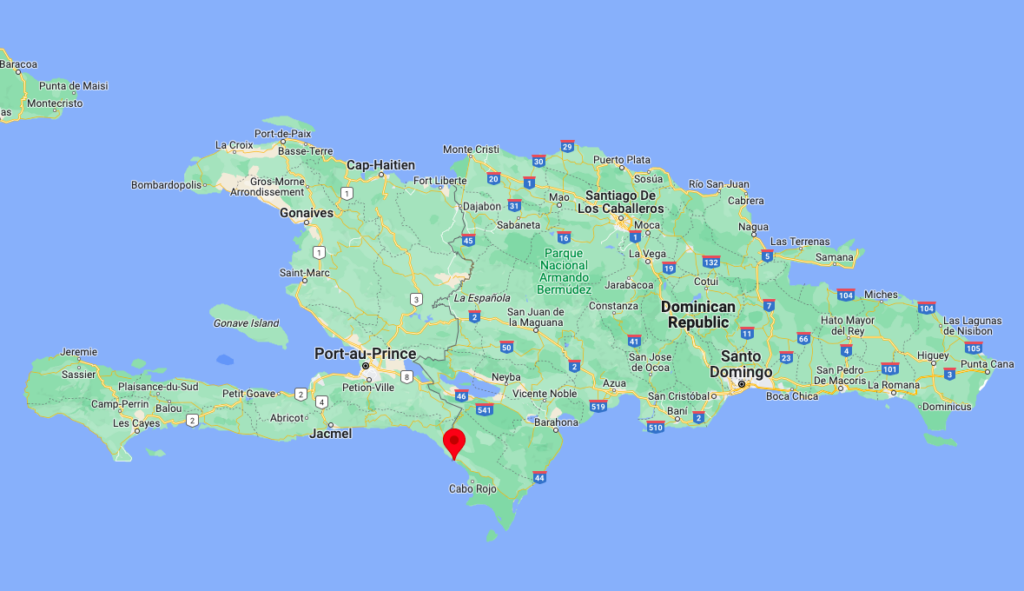

A mambo and hougan—the traditional voudou priestess and priest—lead ancestral ceremonies before rallies take the streets and block the central arteries of Port-au-Prince, Cap Haïtien, and other Haitian cities and towns. After one of their members was kidnapped, leaders of the Protestant Church directed its congregation to halt all activities at noon on Wednesday and bat tenèb. Bat tenèb, literally “beat the darkness,” is a call for all sectors of Haitian society to beat pots, pans, street lights and anything else as a general alert of an emergency. A Catholic church in Petionville held a mass with political undertones against the dictatorship. When marchers from outside took refuge from the police inside the church, the Haitian National Police tear gassed the entire congregation.

Ti Germain, a well-known Lavalas activist, was hauled away by President Jovenel Moïse’s henchmen for protesting in the downtown Chanmas Plaza last week and has not been seen since. Peasants come together to form self-defense units against land grabs by the Haitian Tèt Kale Party (PHTK, or Haitian Bald Headed Party) and their foreign backers before mobilizing in the streets themselves. With the spiritual hymn of resistance blaring from a sound truck, “A fight remains a fight. My sword is in my hand, I’m moving forward,” tens of thousands of protesters move toward police lines guarding the Delmas 96 entrance, which seals off the Haiti of the 0.01 percent from that of the 99.99 percent.

Showdown: the police, the ruling class & imperialism vs the Masses of People 🇭🇹 Which side are you on? #Haiti 🇭🇹 pic.twitter.com/sxRhwaDN90

— Danny Shaw (@dannyshawcuny) March 29, 2021

Chanting “The People Poetry Revolution!”, young writers and poets took to the streets on May 3 calling for a Haiti where youth have a future. A cultural worker, Jan Wonal, asserts, “They [the imperialists] fashion themselves the messengers of art, literature, history of art. So, for us, cultural revolution against cultural imperialism is an imperative.”

All of Haitian society is in revolt.

Who Cares About Haiti?

CNN, MSNBC, Fox, and the full gamut of mainstream media outlets have paid scant attention to this social insurrection. The headlines—if they mention Haiti at all—have focused on U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Biden regime’s deportation of Haitians to the “civil unrest” of Haiti. The anti-neoliberal rebellion goes unmentioned.

According to one protestor at a mass demonstration, “If we were Hong Kong, Taiwan or in any country the U.S. lists as an enemy, there would be everyday coverage of our movement.”

Solidaridad con el pueblo haitiano 🇭🇹 #Haití Que viva el internacionalismo! pic.twitter.com/YviAUzrxXu

— Danny Shaw (@dannyshawcuny) March 28, 2021

The corporate press only mentions Haiti in the context of a natural disaster, a deadly disease or chaos. Millions of people in motion in a U.S. neocolony like Colombia, Chile or Haiti are not deemed newsworthy. The dominant narrative is people in the streets protesting is not a revolt, but a “political crisis.” It is not convenient for a neocolony to make noise and rise up against the empire’s handpicked lackeys and puppets.

In response to the media whiteout, Haitian intellectual Patrick Mettelus emphasized, “Our national liberation struggle is first and foremost a battle of ideas; it is an informational war. How can we counter the dominant narrative and show what is good, beautiful, encouraging and hopeful from our homeland?”

Showdown: Haiti vs. Imperialism

Ignoring months and years of widespread anger, Moïse continues to say resigning is not an option. The United Nations and Organization of American States (OAS) agree the U.S.-backed despot has another year remaining in his presidency, even though the 1987 Constitution stipulates his term ended on February 7. Former president Jean Bertrand Aristide called the UN, OAS and United States “the troika of evil” for the heavy-handed role they have played in Haiti’s historic destiny. This alone explains why Aristide was twice the victim of coup d’etats orchestrated by these neocolonial forces.

Moïse went before the United Nations General Assembly on February 24. In a 28-minute display of arrogance, the tone-deaf puppet patted himself on the back for supposedly carrying out ongoing socio-economic reforms. Adding insult to injury, Moïse now intends to brazenly overturn the 1987 constitution. This constitution was the result of consultations among hundreds of local committees representing all sectors of society一women, peasants, poor neighborhoods, etc.一coming together on the heels of the 1986 dechoukaj (uprooting) that overthrew dictator Jean Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier. Enshrined in the constitution is protection of Haitian cultural and economic sovereignty, and women’s empowerment, among other democratic rights. Today, these same sectors, representing the vast majority of Haitian society, are taking to the streets against Moïse and his dictatorial scheme to overturn the people’s constitution.

The reformist wing of the opposition has propped up a transition president, Joseph Mécène Jean-Louis, who has been in hiding since February 7, in fear of persecution of Jovenel’s National Intelligence Agency (ANI). Ruling class families such as the Vorbe/Boulos faction, which supported Jovenel (and Michel Martelly before) have now turned on Moïse and want to replace him without systemic change.

Kidnappings have reached epic proportions. The djaspora (Haitians in the diaspora) are afraid to travel back home. The Center for Human Rights Research and Analysis reported 157 kidnappings in the first three months of 2021. This lawlessness is representative of a society that has lost all confidence in Moïse. The most oppressed layers of society have been overwhelmed by the weak gourde (1 U.S. dollar equals 87 Haitian gourdes), widespread joblessness and no hopes for a dignified future. According to the UN’s World Food Program, half of Haiti’s 10.7 million people are undernourished. This bleek social reality has pushed the most castaway to resort to armed violence and taking hostages.

The fundamental demand of the popular sectors is a “sali piblik,” or a united transition away from dictatorship and neocolonialism that involves and empowers the masses of Haitian people.

While the corporate media silences Haitian voices, the Committee for Mobilization Against Dictatorship in Haiti (KOMOKODA), Leve Kanpe, the U.S./UN Out of Haiti Coalition, and other diaspora and anti-imperialist organizations across the United States and the world are standing with the historic Haitian rebellion.

“The ‘Core Group’ is a cabal of predatory countries and institutions created by the United States of America after the overthrow and kidnapping of President Aristide in 2004 to give a veneer of international legitimacy to their domination over Haiti,” KOMOKODA stated as the group protested May 3 in front of the French embassy in Port-au-Prince, “Join us as we stand in solidarity with the Haitian people, who are in the streets fighting for their liberation and their emancipation.”

Danny Shaw is a professor of Caribbean and Latin American Studies at the City University of New York. Since the most recent rebellion began on February 7, he has traveled to Haiti twice to stay with the mass anti-imperialist movement. A Senior Research Fellow at the Center on Hemispheric Affairs, Danny is fluent in Haitian Kreyol, Spanish, Portuguese and Cape Verdean Kriolu.