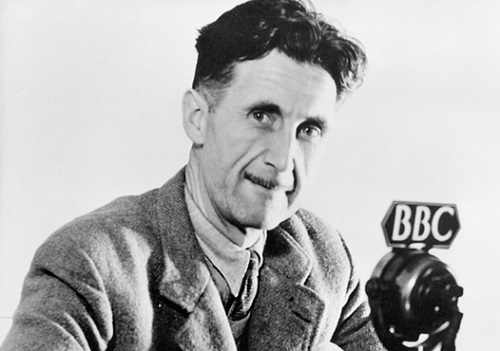

Reviewed: George Orwell: The Complete Poetry, ed. Dione Venables, Published by Finlay for The Orwell Society, 72 pages, £8.99.

George Orwell is remembered as an essayist, a novelist, a cultural critic, and a critical socialist but not, generally speaking, as a poet. Yet he did write poetry — nonsense poetry, political poetry, romantic and lyrical verse, even the odd limerick. He wrote for pleasure, for friends and lovers, and for publication; and he incorporated bits of rhyme into his novels and journalism.

Finlay has just published a collection of Orwell’s poetry for The Orwell Society. It’s a slender, handsome volume, pleasant to hold in hand and quick to read. The book collects all forty-three surviving poems, more or less: the authenticity of a few is in doubt (and this is noted in the text), while several distinct couplets are grouped together as “Scraps of Nonsense Poetry.” A long essay by Dione Venables — part biography, part criticism — gracefully connects (or sometimes as importantly, distances) the very different items and turns what might easily have been little more than an extremely uneven chapbook into an insightful study into the development of a great writer.

The collection, arranged chronologically, begins with the Kiplingesque “Awake! Young Men of England,” written soon after the outbreak of the Great War by the eleven-year-old Eric Blair. The patriotic theme continues with 1916’s surpassingly competent “Kitchener,” commenting somberly on the Field Marshal’s death by drowning, the victim of a nautical mine. Indeed, though with greater irony, some of Orwell’s mature poetry is observably borne of the same patriotic impulse — especially “As One Non-Combatant to Another,” his biting reply to the pacifist Alex Comfort in the midst of the Second World War:

“And in the drowsy freedom of this island

You’re free to shout that England isn’t free;

They even chuck you cash, as bears get buns

For crying ‘Peace’ behind a screen of guns.”

Between the wars, Orwell went to Eton, and then to Burma; he tramped around London, washed dishes in Paris, taught school in Hayes, and commanded troops in revolutionary Spain. Each period left a mark upon Orwell’s writing. Satires upon school life in the style of Whitman, Coleridge, and (yes) Kipling (“If you can keep your face, when all about you Are doing their level best to push it in…”) appeared in the Eton paper College Days. Burma inspired bawdy songs about prostitutes, gloomy meditations on the apocalypse, and an epitaph in verse for “John Flory,” later the name of the protagonist in Burmese Days: “Money, women, cards & gin Were the four things that did him in.”As schoolmaster he wrote a play, King Charles II; one speech in verse, notable chiefly for its Royalist sentiment, is included in this collection.

Yet as his prose gained momentum the poetry lagged, and the poetic comment often trailed the event in question by some number of years Orwell wrote no verse, or none that survives, during his days “down and out,” though he did later write a humorous poem about two men “by the kip-house fire.” One is naked and the other hungry, so they start “Bargaining for a deal, Naked skin for empty skin, Clothes against a meal.” Likewise, any poetry Orwell wrote in Spain would have been confiscated, along with his journals, by the NKVD. Later, though, he wrote touchingly of meeting an Italian militiaman there:

“Good luck go with you, Italian soldier!

But luck is not for the brave;

What would the world give back to you?

Always less than you gave.”

There remains in these lines something of the boyish sense of duty that characterized “Awake! Young Men of England” but the allegiances of the poem are broader, and its insistent praise is colored by the knowledge of defeat.

Alongside the topical and political poems, there are others, in a way more personal. Orwell wrote plaintively of love and friendship to his adolescent sweetheart, Jacintha Buddicom:

“Friendship and love are closely intertwined,

My heart belongs to your befriending mind;

But chilling sunlit fields, cloud-shadows fall —

My love can’t reach your heedless heart at all.”

(This collection also includes Buddicom’s almost too-gracious reply:

“By light

Too bright

Are dazzled eyes betrayed;

It’s best

To rest

Content in tranquil shade.”)

There are also, somewhat later, a set of poems from the Adelphi literary journal, suddenly full of proper adult themes like the shortness of time, and the pain of indecision, and the denial of happiness by the poor luck of being “born, alas, in an evil time.” These are surely the most polished poems in the book, yet they would hardly on their own be enough to justify such a collection.

What are more interesting, I think, are those bits of poetry that found their way into Orwell’s other writing. These would include, most famously, the strange, sad, “Chestnut Tree” poem from 1984, along with Animal Farm‘s oddly moving “Beats of England,” the deliberately banal “Animal Farm, Animal Farm,” and the hilariously appalling “Comrade Napoleon” (“Friend of the Fatherless! Fountain of happiness! Lord of the swill-bucket!”) But there is also a silly couplet from Burmese Days, the “Italian Soldier” poem quoted earlier (which appeared as part of the essay “Looking Back on the Spanish War), and — perhaps my favorite of the volume — “St. Andrew’s Day,” from Keep the Aspidistra Flying.

In fact, the real value of The Complete Poetry may not be the poetry at all, or even Venable’s worthy framing essay. The real value may be that the poetry offers a new angle from which to view Orwell’s prose. It is not simply that they touch on similar topics, though often they do. It’s that the poetry and prose both reflect a deeper shared approach to their subject, whatever that may be. The quality of the work, even when it is lacking, nevertheless expresses those concerns Orwell mentioned in his essay “Why I Write” (quoted in this volume as an epigram): “So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information.”

Indeed, reading through the full set of Orwell’s poems, one is not struck with wonder at how good (or, too often, bad) they are, but is reminded instead of how splendid his prose is. Ironically, one is driven to the conclusion that the remarkable lasting quality of his prose work owes much, not to his poetry exactly, but to his poetics.

Venables makes this point expeditiously by breaking a passage from 1984 into discrete lines, turning it into a poem, with admirable results. A great many of Orwell’s lyrical, descriptive passages could surely withstand similar treatment, as could any number of his famous lists, and perhaps even some of his straightaway argumentation.

Still, the poetics of his prose must remain paradoxical. Orwell famously stated that “Good prose is like a windowpane.” Smooth, clear glass allows us to see without obstruction, practically without notice. We look through the glass; we do not look at the glass. Yet, ironically, his success in transparent composition undoubtedly relied on his careful attention to the language itself, the rhythm and tenor of the words, the play with connotation, the selection of just the right phrase, the use of fresh, arresting imagery. In poetry, the process of language is inescapable. It often feels forced, and the effect of the poem is spoiled as a result. That is true of Orwell’s, as much as anyone’s. With his prose, however, it is just the opposite. The language feels natural, and it is almost possible to forget that there is a difference between reading and thinking. Poetry is stained glass; it shows us, most of all, itself. It forces us to see the language, and Orwell’s poems sometimes fail as a result. But his poetry, by virtue of its very weaknesses, may help us to understand the strengths of his prose. It may teach us, at last, to really see that writing, so clear, seems sometimes almost to vanish.

Kristian Williams is the author of Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America, American Methods: Torture and the Logic of Domination, and Hurt: Notes on Torture in a Modern Democracy. He lives in Portland, Oregon.