El Salvador is now the first country in the world with an all-out ban on the mining of gold, silver, and other metals. The country’s legislative assembly passed a bill to that effect last week, on March 29.

The historic news quickly made headlines around the world, but much of the coverage has obscured the true protagonists of the story. The tagline used by The New York Times to describe its April 1 editorial makes this crystal clear. “Officials in El Salvador showed exemplary foresight in banning mining of gold and other metals,” according to the embedded line of text that shows up in links to the editorial on the newspaper’s website and on social media.

There was no such exemplary foresight.

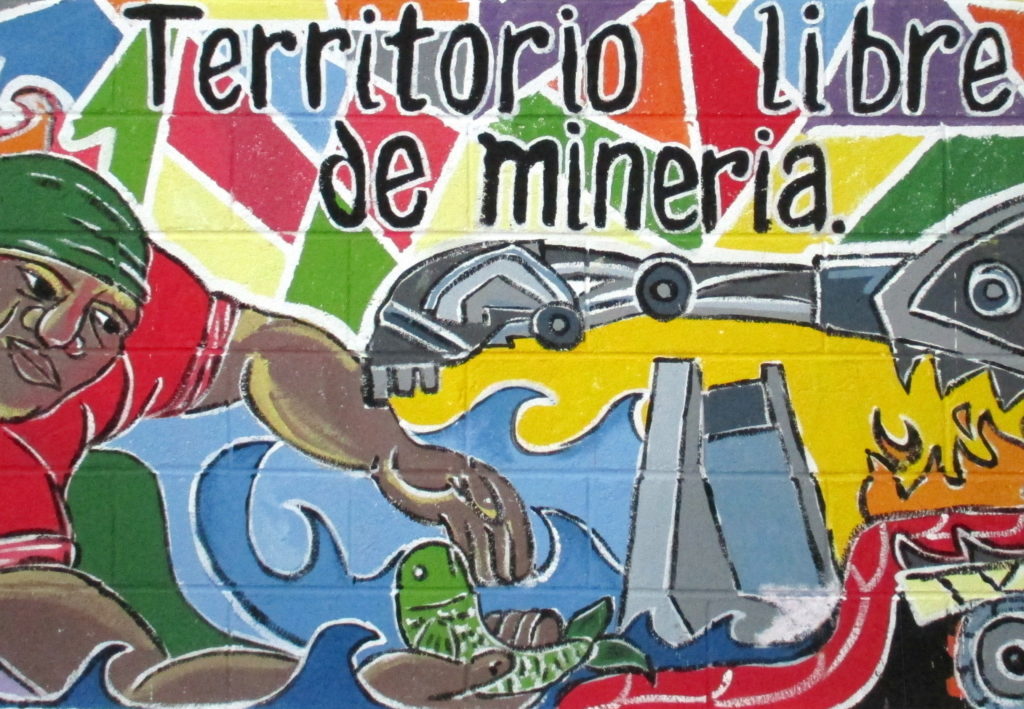

For years, communities and groups around the country organized, raised awareness about the issue, took direct action, formed a National Roundtable against Metallic Mining, campaigned for an all-out ban on metals mining, drafted and submitted bill proposals, held marches and protests, reached out to potential allies in the home countries of mining companies, and carried out municipal-level referendums on mining.

And for years, most legislators did nothing.

“Mining is in no way viable for El Salvador,” Vidalina Morales, an outspoken anti-mining activist and president of the Association for the Social and Economic Development of Santa Marta (ADES), told Toward Freedom. “For so many years, our demand of the legislative assembly has been the approval of a law [banning mining].”

The Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front party (FMLN) ended up incorporating the grassroots demand for a ban on metals mining into its platform. Named after the left-wing guerrilla forces it grew out of following the 1992 peace accords that ended a 12-year armed conflict, the FMLN has won the past two presidential elections, but have not held a majority in the legislative assembly. The right-wing Nationalist Republican Alliance party (ARENA) and center-right Grand National Alliance party (GANA) were able to block any attempts to advance legislation banning mining.

Most legislators did nothing when community leaders fighting the El Dorado gold mining project were killed. When activist and cultural center director Marcelo Rivera was abducted in June 2009, or when his body was found with signs of torture the following month. When Cabañas Environmental Committee vice president Ramiro Rivera was shot in August 2009, or when he was killed that December. When committee member Dora Recinos Sorto, eight months pregnant at the time, was killed six days later. When others were threatened, attacked, and killed.

At that point, the executive branch had already decreed a moratorium on mining in 2008 and refused to issue any licenses. The El Dorado project had already been denied key permits, and the company behind the project had already filed a claim against El Salvador with the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) in 2009 that it later upped to $301 million before eventually losing its case last year. During that period, the finality of a legislated ban might have redirected the focus away from the community activists who wound up being killed, but exemplary foresight wasn’t on the agenda, and most legislators did nothing.

Community action, on the other hand, never let up. Deposits of gold and other metals are largely concentrated in the northern half of El Salvador, but geographic location isn’t the only commonality among local grassroots anti-mining struggles. The resistance of many of the communities most involved in the movement against metals mining has been informed by their experiences during and after the 1980 – 1992 armed conflict.

An estimated 75,000 civilians were killed during the conflict and another 8,000 were disappeared. A United Nations Truth Commission reported that, according to the reports and testimonies it had received, more than 85 percent of cases of extrajudicial executions, torture and other abuses were attributed to agents of the state and allied paramilitary groups and death squads. During that same period, the United States provided the Salvadoran government with several billion dollars in economic and military aid.

Because of their experiences, accepting defeat in the struggle against mining was never an option for many Salvadoran communities, according to CRIPDES president Bernardo Belloso.

“Do you know why? Because these lands were never given, nor were they inherited. These lands were conquered as a result of the armed conflict that took place in our country. The blood and dead of many people who are their relatives – their children, their aunts and uncles, their grandparents – are found in these lands. That is to say, for us, it’s sacred land,” he told Toward Freedom earlier this year.

Belloso was in Cinquera to support the municipality’s referendum on mining. The February 26 event was the fifth of its kind in the country and the first to take place in the department of Cabañas. The first four were held in 2014 and 2015 in neighboring Chalatenango.

CRIPDES has accompanied communities in the region since long before the referendums on mining. The organization began as a human rights organization during the repression of the 1980s and later accompanied the return and resettlement of people and entire communities that had been forced to flee to other parts of El Salvador and to refugee camps like Mesa Grande in Honduras.

“A small portion of people returned to their places of origin. Others of course had to find other lands to occupy and then create settlements,” said Belloso. Communities in Cinquera and other nearby municipalities in Cabañas and Chalatenango include a mix of returnees and other resettled refugees, he said.

“It was necessary to take lands from the big landowners at the time in our country to accommodate large numbers of people, and to then fight for the legality of those lands to be able to issue deeds to the different people that had occupied them,” said Belloso. That process, he added, “was of course established through the peace accords.”

When mining companies turned up in the lands of these resettled communities, people already knew what destruction could look like because their lands and villages had been militarized, set ablaze, and bombed. They knew what forced relocation entailed because they had been forced to flee. Perhaps most importantly, they knew how to effectively organize because they had to in order to survive in the mountains and in refugee camps, and later in order to resettle and rebuild communities when they returned.

Canadian and US mining companies were engaged in exploration activities in El Salvador in the early 2000s, but the response on the ground wasn’t the same across the board. In one area, grassroots resistance efforts came together, but did so amid political divisions and varying levels of organizing experience, and a mining company managed to install itself and advance the El Dorado gold mining project. In another region, people mobilized immediately and kicked mining companies out.

Regardless of how they developed in different places, the local struggles against mining in El Salvador have been the driving forces behind the national movement. In fact, the largely uphill battle against El Dorado and the courageous involvement of community residents despite great personal risk, as evidenced by the above-mentioned killings, probably constituted the most important inspiration and reference point for the national movement, and for international attention. But how and why resistance unfolded so differently just 30 miles to the north is worth noting.

In Chalatenango, people mobilized at the first sign of strangers planting stakes in the lands they began resettling towards the tail end of the conflict. As soon as they investigated what the stakes were all about, they took direct action and promptly kicked the mining companies out.

“We defend the territory by any means necessary here,” Ana Dubón of the Association of Communities for the Development of Chalatenango (CCR) told Truthout on the eve of a 2015 municipal referendum on mining in Nueva Trinidad.

It is no coincidence that the first four municipal referendums on mining held in El Salvador also took place in resettled areas of Chalatenango, where local organizing processes are strong. Relative political unity has also meant that the people residents have elected to local governments often share their views and experiences – as massacre survivors, as returned refugees, or as former guerrilla combatants – and represent the collective interests of communities. Regional and national organizations like CCR and CRIPDES have been accompanying and supporting residents’ local organizing processes and initiatives for decades.

The fifth municipality in El Salvador to hold a referendum on mining, Cinquera is located in the department of Cabañas, but its history is similar to that of the Chalatenango communities where the previous referendums took place. The lands residents of all five municipalities have been fighting to protect from mining companies are scattered with blood and bones.

The legislative assembly’s March 29 vote is historic and deserves every bit of attention and celebration it has received. Likewise, the rare moment of unity between legislators from the three major political parties, as well as from other smaller ones, who came together to advance and then pass the bill banning metals mining has rightfully been lauded.

Even so, while legislators may have been the ones casting votes on the floor, they weren’t the ones with exemplary foresight. Beneath the surface, the ban did not become a reality because of them. It became a reality in spite of them.

The victory belongs to the communities that have been engaged in local resistance movements, and to the organizations that have accompanied and supported them for years on the ground. It is a testament to decades of struggle.

#

Sandra Cuffe is a freelance journalist based in Central America, where she covers environmental, indigenous, and human rights issues. You can find her on twitter at @Sandra_Cuffe or read more of her work on her website at sandracuffe.com.