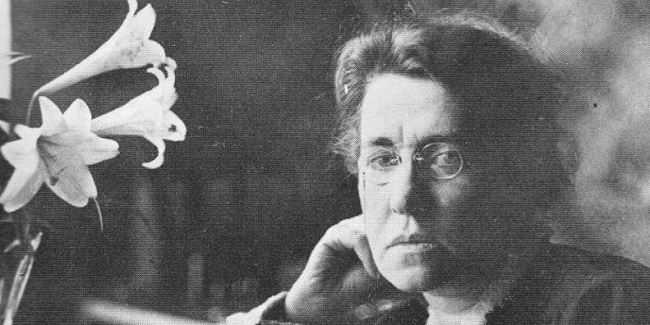

Emma Goldman

To say that you believe in a society dedicated to individual liberty rather than top-down authority or force sounds as American as apple pie. At least it should. But when the person saying it calls him or herself an anarchist, those same views are often decried as un-American or treasonous.

Anarchists have been tarred for a century as subversives, bomb-throwers, terrorists; deluded utopians at best. But no “ism” is more misunderstood, purposely distorted or entwined with America’s traditions of self-government and free speech.

Even in Vermont — a place much associated with socialism since the first election of Bernie Sanders as Burlington mayor back in 1981 — anarchists of the past have found it hard to win a hearing. In fact, Emma Goldman, a charismatic spokeswoman for this libertarian socialist ideal, once tried to explain her beliefs to Burlingtonians only to find the doors barred to her entry.

Why such hostility? In a sense, the real confusion began in 1886, just days after America’s first May Day mobilization. The five-year-old American Federation of Labor called for strikes on May 1 wherever companies were refusing the eight-hour workday. More than 350,000 people across the country responded. But in Chicago the powers-that-be decided to make an example of the strike leaders if anything went wrong. Something did. And some of the organizers were anarchists.

On May 4, the night after a fight between strikers and strikebreakers during which police shot several people and killed one, a protest rally was held in Chicago’s Haymarket Square. As the rally was breaking up a bomb exploded. Several policemen were killed, and the event was called an “anarchist plot.” A campaign of repression was immediately launched against anarchists everywhere.

The true culprits were never identified, yet eight anarchists were convicted of the crime and four of them were hung. For decades the word anarchist remained etched in the public mind as a synonym for political violence. Its actual meaning was seldom discussed.

Anarchists, Marxists, Socialists. Most people don’t realize there’s a difference. A common perception is that anarchists, like Marxists and some Communists, want the state to control the “means of production” and feel individual rights must sometimes be sacrificed to create a “dictatorship of the proletariat.” Nothing could be further from the fiercely libertarian values at the heart of anarchism.

Free speech, for example, has always been a central tenet for these believers in diversity, decentralization and self-management. Ironically, they have regularly been denied this basic right — even in Burlington.

“Is there free speech and fair play in Burlington?” So went the headline of a flyer distributed in the Queen City on Sept. 3, 1909, the date when Emma Goldman was scheduled to speak at City Hall on “anti-militarism.” The answer to the question turned out to be an official “no.” Mayor James Burke, in many ways a champion of progressive ideas, would not let Goldman “preach any of her un-American doctrines.”

The anarchist writer had just addressed audiences in Barre, where radical ideas were taking hold, and Montpelier, the state capital. But an attempt by her manager Ben Reitman, known as the “king of hobos,” to rent City Hall in Burlington was denied. Although Reitman did manage to find a private hall, Burke showed up with two policemen to prevent the talk.

Goldman protested that she had the same free speech rights as any person in America. But the mayor insisted that she not speak in public, “in the name of peace, of society, and of law and order.”

On other occasions, when free speech did prevail, Goldman often won the respect and affection of many listeners when she described a free society in which all people cooperate on a voluntary basis, a society without armies or authoritarian bureaucracies. Like many anarchists, she believed that people are basically good, and that they can solve their own problems, face to face, without the imposed force of centralized government.

“Peace and harmony,” she once wrote, “between the sexes and individuals, does not necessarily depend on a superficial equalization of human beings; nor does it call for the elimination of individual traits and peculiarities. The problem that confronts us today…is how to be one’s self and yet in oneness with others, to feel deeply with all human beings and still retain one’s own characteristic qualities.”

This focus on diversity, along with liberty and mutual aid, is consistent with America’s libertarian ethic. The ideals of free expression, decentralized power, individual rights and participatory democracy run deep in our history. In fact, many people who put themselves on the right end of today’s political spectrum share these values with those on the left.

Libertarianism is often defined by the “free market” fealty of the right. But this approach, confusing suspicion of centralized power with rejection of any government activity, isn’t the only option. Instead, it can mean a decentralized society based on popular assemblies (in Vermont we call them Town Meetings), an ecological ethic, and mutually supportive confederal relationships between communities. This is a vision of widely distributed power and wealth, of liberty, self-reliance and community.

Some weakness can certainly been found and libertarians have occasionally veered into extremism. But in an era when freedom and diversity are threatened by dehumanizing institutions, sometimes “extremism is defense of liberty is no vice.” Barry Goldwater’s 1964 rallying cry is one that many still embrace.

No “ism” can cure all of society’s ills. But by understanding the true similarities and differences among them, in considering and comparing the messages of capitalists and socialists and also anarchists, we may find our way to a freer future. In the process, hopefully, we can learn to “agree to disagree” for the benefit of all.

On May 2, 1983, this column was published on the editorial page of The Burlington Free Press, the daily paper in Vermont’s largest city. One month later, hundreds of activists marched through Burlington for a protest at the GE Gatling Gun plant in the city’s south end. The author joined almost 100 of them who participated in a sit-in and were arrested on orders of another progressive mayor, Bernie Sanders.

Greg Guma has been a writer, editor, historian, activist and progressive manager for over four decades, leading progressive organizations in Vermont, New Mexico and California. He worked with Bernie Sanders in Burlington and wrote The People’s Republic: Vermont and the Sanders Revolution