“To me, socialism doesn’t mean state ownership of everything, by any means, it means creating a nation, and a world, in which all human beings have a decent standard of living.” — Bernie Sanders, 1990

Bernie Sanders has a plaque honoring Eugene Debs on the wall of his Senate office in Washington. It is an abiding admiration, stretching back decades. Before becoming Burlington mayor in 1981 — but after four “third party” races for statewide office in the 1970s — he produced and narrated a 28-minute documentary, Eugene V. Debs: Trade Unionist, Socialist, Revolutionary, 1855-1926.

For a better understanding of Sanders’ philosophy and style, it helps to know a bit about the political figure he admired as a young radical in Vermont, during and after the Vietnam War.

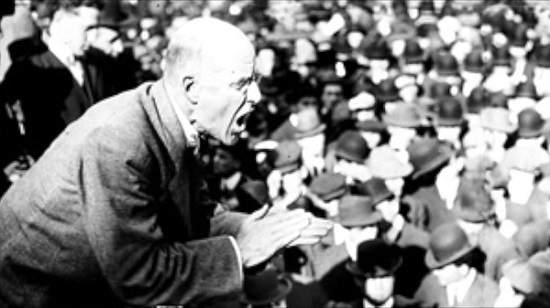

A century ago, American politics was dominated by men who could command a public stage, telling jokes and stories with ease, making arguments and issuing indictments in long speeches. Of course, most of them relied on prepared remarks, but Eugene Debs seemed to speak from the heart. No tricks or effects, just electrifying straight talk.

Much like Bernie Sanders, Debs could inspire a crowd. He could be angry and funny, sarcastic and sentimental, sometimes poetic or even prophetic. But his target was always the same – big capitalists and their bankers, judges, politicians, editors, and even conservative union leaders. He called on workers to join a moral struggle against “wage slavery.” Industrialists were making a mockery of democracy, he charged, using their control of production to pervert the will of the majority.

For more than 30 years Debs was the most visible (and often controversial) spokesmen for a socialist vision in America. Critics said he was a menace, an apostle of anarchy and chaos. Eventually, he went to prison for his anti-war beliefs. In the end, the movement to free “democracy’s prisoner” launched the American Civil Liberties Union and changed the terms of free speech during wartime.

In 1894, Debs first took center stage in the growing struggle between industrial capitalists and their workers. It was during one of the most dramatic and disruptive labor protests in American history — the American Railway Union strike against the Pullman Palace Sleeping Car Company.

By 1901 he had moved from preaching about a cooperative commonwealth to openly promoting socialism as leader of the new Socialist Party of America. By then a “professional revolutionary,” he ran for president every four years. The party had 150,000 members by 1912, and had elected hundreds of people as mayors, councilors, commissioners and state representatives.

As the centerpiece of the ongoing Socialist campaign, Debs often toured the country in a Red Special railcar filled with posters, reporters and party dignitaries. At the height of the tours he gave hundreds of speeches a month, consistently mesmerizing his audiences.

In 1912, Debs kicked off his fourth presidential campaign to a sold-out crowd in Madison Square Garden and received a half-hour standing ovation. It was the same everywhere he went. He painted vivid word pictures of worker slaughter in mines and mills and the impending battle between “the multi-millionaire and the pauper.” He touched an emotional core for anyone concerned about the new concentrations of wealth, even if they were skeptical about his socialism.

Part of the appeal was his claim to be part of the working class. Debs was largely self-educated and began working on the railroads at fourteen. From there he became a union leader. But his message also had appeal for middle class men and women (even though the latter couldn’t yet vote).

Critics saw socialism as an alien ideology, imported by immigrants. But Debs challenged that notion. He was a midwesterner, fighting capitalism in the spirit of Tom Paine and Walt Whitman. To back it up, he lived a conventional middle class life with his Kate in Terre Haute, Indiana, a small industrial city.

In the turning point presidential race of 1912, Debs argued that both Woodrow Wilson, the Democrat, and Theodore Roosevelt, running on his reform “Bull Moose” party platform, missed the main point — that workers and owners were natural enemies with irreconcilable interests. Both were trying to ease the symptoms of injustice, but ignoring their cause.

That year Debs got almost a million votes, doubling his 1908 tally. It looked like the Socialist Party and Debs were here to stay. But then came World War I, and in its wake Debs ended up in federal prison in 1919 for speaking out against war. A year after that, as a movement built for his release, he ran for president again. Before the end of 1921, he was released by President Warren Harding.

Although Debs didn’t get as far as Bernie Sanders in persuading Americans to join a political revolution and consider socialist solutions, he began the dialogue. Debs also provoked a national debate about the meaning of the First Amendment. In a post-war age of oppressive conformity, he sparked the birth of the modern civil liberties movement and convinced many people that society should better protect those who dissent, especially when they refuse to support the majority in the heat of war.

It’s easy to see why Bernie Sanders, already the longest serving Independent in US congressional history and leading US voice for democratic socialism today, still admires him. But he has some distance to go to match Debs’ enduring impact and legacy.

Greg Guma is the author of The People’s Republic: Vermont and the Sanders Revolution.