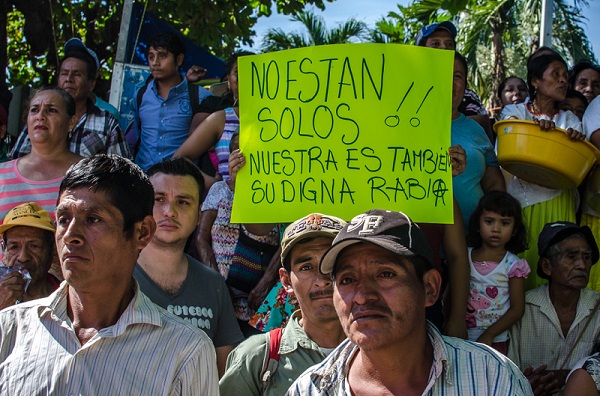

The enforced disappearance of 43 students from the Ayotzinapa rural teachers college has catapulted Mexico’s security crisis into the international spotlight and revealed the deep-seated ties between the government and organized crime. It has also brought to the forefront the dignified struggle and courage of the families of these students who refuse to believe that their sons have been reduced to bags of ashes, which according to the Mexican Government was the fate that they met.

The students were last seen when their bus caravan was violently attacked numerous times by municipal police and armed men in Iguala, Guerrero on September 26, 2014. These attacks left 6 people dead and the 43 students who were detained by police have not been seen since. This attack and enforced disappearance has provoked outrage on national and international scale and a new level of organizing on a local level in dozens of municipalities across Guerrero.

Social activists, campesinos and students have formed the Popular National Assembly and meet on a regular basis at the Ayotzinapa school to strategize and plan actions to demand that the students be returned alive. On October 24th 2014 the assembly voted to advance the movement by trying to take over the city halls in all 81 city halls in Guerrero to “establish popular assemblies, municipal popular councils and exercise power by constructing their own system of justice and community police.”

On November 29th, 2014 members of the CETEG, a state teachers union known for its radical tactics along with the citizen police force took over the Tecoanapa city hall in Southern Guerrero and established the Popular Municipal Assembly. “We asked the municipal president to demand justice regarding the 43 students who were disappeared. We saw his delay in responding because he didn’t want to lose privileges and resources that [former] Governor Aguirre granted him,” said Jose Felix Rosas Rodriguez, teacher and spokesperson for the Popular Movement in Teocoanapa, a largely rural municipality in the Costa Chica region.

“The president offered 200 pesos (14 dollars) to the family members of the disappeared which is just crumbs,” added Rosas Rodriguez.

Eight of the disappeared students hail from Tecoanapa including Alexander Mora Venancio, whose remains were taken from a bag of ashes the government claims came from the Cocula Garbage dump, where they say the Normalistas were killed, have been the only ones to be identified by the independent Argentinian forensic team. However the team says they cannot confirm that the ashes came from this garbage dump because they were not present for their extraction.

City Halls were taken over in 49 other municipalities and to the date the Popular Assembly says that over a dozen city halls are still being occupied. The state government of Guerrero was contacted to comment on these occupations but was not available to respond in time for publication. In the majority of the municipalities it appears that the government has established alternative offices, although no official was able to confirm this.

Rosas Rodriguez believes that the government’s inaction while faced with such a serious crisis led the townspeople of Tecoanapa to reflect on city hall’s role in their lives. “People go in there poor and they come out rich,” remarked Rosas. “Those who govern us have relationships with criminals, they launder money and steal resources.”

A recent article published by the Mexican newspaper Milenio stated that at least 12 mayors in Guerrero have likely relationships with drug cartels, based on information they say they received from government security agents. Tecoanapa’s municipal president, Manuel Quiñones Cortés was not on the list but residents say he did little to provide security to the area’s residents.

A few years back, a spike in kidnappings and extortions in this area led to the creation of a citizen’s police force started by the UPOEG (Union of Communities & Organizations in Guerrero State.) This citizen police force was a splinter from an already existing community police force the CRAC that has existed for more than 18 years and largely operates in indigenous communities in Guerrero. This January, the UPOEG just celebrated their two-year anniversary of their Security System and Citizen Justice, which helped bolstered resident’s faith into taking political matters into their own hands.

“The situation was very bad before, you couldn’t go out at night, they would extort you, and there were ambushes. Now with the community police everything is much more relaxed and you can walk around without any problems,” said 20-year-old Ulises Morales who is a Junior at the Ayotzinapa school.

During his school vacation Morales travelled to Tecoanapa to help his family with their hibiscus flower harvest and says he was impressed with all the organizing going on. “Here we lack many things, many of the communities don’t even have proper drainage systems, there aren’t enough doctors nor schools to help raise consciousness among the people,” said Morales who is the first in his family to achieve higher education. “If the people who governed around here were campesinos, they would understand the communities problems like the need for more farm machinery to help them with their crops,” he added.

According to coordinator, Rosas Rodriguez, teachers have been at the forefront of this process but he hopes the organizing can be distributed in a more horizontal fashion to include more professionals that will compose the public works, treasury and budgeting, health and education committees.

The municipality of Ayutla de los Libres is less than 15 miles down the road and is home to four of the disappeared freshmen and one student Aldo Gutiérrez Solano who remains in a coma after being shot in the head during the attack. The central plaza is buzzing with activity and posters hang on the city hall walls outlining all the work that needs to be done to maintain their encampment with spaces for volunteers to write their names.

A group of teachers have just returned from the field where they were meeting with people in a handful of the 113 surrounding communities to see if they wanted to participate in the Municipal Popular Council. Each community was asked to name their popular council representative in a document that denounced the repression against the Ayotzinapa students.

“The corruption that exists in the municipalities and the political class of all of the parties has allowed organized crime to flourish in the streets of our municipalities in a complicit matter with the crimes that are committed against a defenseless population,” reads the forming document. The document also lists various articles of the Mexican Constitution, which state that indigenous communities have the right to govern themselves. The teachers who have been collecting signatures, and preferred to remain anonymous, said that they believe that there is a more than 70% approval rating for the council.

In many rural areas in Guerrero there is an already existing structure of commissioners who represent ejidos (communal farm land) and are elected on an annual basis. The popular council would tap into this local governing system but divorce itself from all political parties who currently have much influence in the ejido structure.

While these processes are happening on a local level, they have the potential to have an impact on a national and even international scale. “We are living in one of the worst eras that our country has faced, it is traumatizing, and complex with a criminal state that doesn’t respect the law nor the constitution. “ said Gilberto Lopez y Rivas, a 72 year old Mexican scholar who has written various books and articles about autonomous processes.

Lopez y Rivas said, “Zapatismo has always been a important reference of autonomy” and added that now, “Ayotzinapa has forged this very important path, that is at the crux of this autonomous process.”

The teachers in Ayutla also said they have been inspired by the Zapatistas and are well aware of their rights both as Mexican citizens and indigenous communities. “We want an Ayutla where equality exists. We recognize that the constitution includes Article 39 that says that the people have in any moment the right to get rid of and install the political authority that they believe would be better and who will comply to satisfactorily secure their well-being,” remarked one of the teachers.

Just as the Zapatistas have continually called for the removal of military forces in Chiapas, so have the people of Tecoanapa and Ayutla. On December 17, 2014 along with family members and students of Ayotzinapa they marched on a local military barracks demanding that they close down and leave the area. The soldiers still remain on post, and the citizens still have the same demand.

A few hundred miles away in Tlapa, the municipal center of the mountain region of Guerrero, a similar scenario is unfolding. Residents have also taken over the Tlapa City Hall as well as city halls in over a dozen surrounding towns and are holding assemblies to plan how their new region council will function. “We don’t want top-down power,” said lawyer and local activist Arnulfo Soriana in an interview with Toward Freedom. Soriana who is of Nahuatl descent explained that they are envisioning a return to a government based on the habits and customs of the various indigenous communities in the area.

He says they have also met with Zapatista leaders as well as people from Cherán, Michoacán. The residents of Cherán rose up against what they deemed as a “Narco-Government” in 2011 kicked out the local government and formed their own community police force to protect the townspeople and the surrounding forest from illegal logging. The town is currently governed by the indigenous Purépecha habits and customs but they still receive their budget from the state and federal government.

“We want the congress to approve legislation so that we can receive resources for the health, commerce, public security, attention for women and migrants. Before the politicians didn’t do anything, they just came in to get their paychecks,” said Soriana.He added, “We want to return to our collective beliefs that indigenous communities have always believed in.”

With elections around the corner it is evident that the government in Guerrero has started to feel the threat of these surging autonomous movements and have thus attempted to co-opt them “They have tried to use our movement’s expressions saying ‘They didn’t know we were seeds’ in their political campaigns but we won’t fall for that and we will not participate in their elections,” said Felipe de la Cruz, spokesperson for the Ayotzinapa families during an educational event in the state’s capital Chilpancingo, about a 1960 movement that demanded the “disappearance of political powers” following a police led student massacre.

While politicians are bolstering their campaigns, community activists in Guerrero say they will be strengthening their popular assemblies and growing their councils. “Here we are looking for a true social transformation so that the murder and disappearance of their children is not in vain,” added Soriana.

***

Andalusia Knoll is a freelance multimedia journalist based in Mexico City. She is a frequent contributor to to VICE News, AJ+, Democracy Now! and Truthout. She has been covering repression against the Ayotzinapa students since 2011 and was one of the first international reporters to cover the enforced disappearance of the 43 students. You can follow her on twitter @andalalucha.