The recent fighting in Ndjamena, Chad on February 2-6 between an alliance of insurgencies and the army of President Idriss Déby Itno has highlighted the transnational politics of Sudan, Chad, and the Central African Republic. Europeans and Americans living in Ndjamena were flown out by French Army planes, mostly to Libreville, Gabon where France has a military airbase. Many ordinary Chadians, an estimated 20,000, walked or drove across the two bridges which span the river Chari into northern Cameroon. Most have now returned when the insurgencies’ hope for a quick victory faded before the support of the French government for Idriss Déby (the Itno part of his name is rarely used.).

A similar lightning attack on Ndjamena had been tried in 2006 and had also failed, the insurgency forces then withdrawing to the frontier area with Sudan or into Darfur. These insurgency attacks were done less to conquer Ndjamena than to test the popularity of Déby and especially the loyalty of the Chadian army toward him.

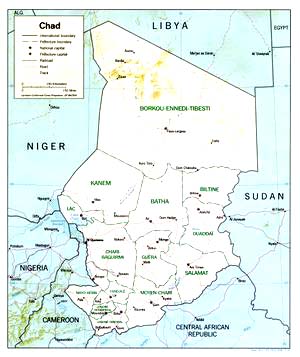

Déby had come to power in 1990 with similar tactics to test the popularity of the then dictator and former anthropology student Hissene Habre. Habre had overstayed his welcome of 10 years as President and, taking all the money that he and his entourage could carry, left for Senegal without a fight. Déby’s nephews are among today’s insurgencies hoping that what worked well for their uncle would work for them. Although the three allied insurgrencies in Chad have political names such as the Union of Forces for Democracy and Development (UFDD) and United Forces for Change (FUC), they are, in fact, clanic struggles for power among ethnic groups from northern Chad which spill over into Sudan and Libya.

What distinguishes the current struggle from the fight led by Déby in the late 1980s is the production of oil and its resulting wealth. When Hissene Habre left Chad in 1990 with all the money he could carry, Chad was a poor, landlocked country of small farmers and herders. There was always money for political leaders to skim off building contracts, renting houses, and French military concessions, but it was still not more than could be carried out of the country. With oil production, the amounts of money available merit trying to stay in power longer.

Much of Chad’s oil industry was financed by loans from the World Bank, and the Chadian government had signed pledges as to the socio-economic use of the oil revenue. When the Chadian government could not account for the use of most of its oil revenue – it certainly had not gone into education, which was part of its pledge – the World Bank under Paul Wolfowitz and his anti-corruption goals had cut off further loans to Chad. Wolfowitz’s World Bank career was short and cutting off new loans will not make past revenue reappear, so Déby will continue to have loans while being unable to say where the oil money has gone.

The other factor that distinguishes the current struggle from the earlier Chadian conflicts is the regional and international context. Déby had organized in the late 1980s his insurgency from Darfur where he had ethnic ties. At that time, Darfur was calm, of no political or economic importance and largely out of sight as the North-South Sudanese struggle went on. Now Darfur is on the international agenda of the UN Security Council, and a joint UN-African Union force is to be sent to replace the largely inadequate African Union force there now.

Some 240,000 refugees from Darfur have crossed into Chad. In Chad, they are neighbors of some 260,000 Chadians displaced by the fighting between the Chadian Army and the Chadian insurgencies. Some of the Darfur insurgencies use Chadian territory for military camps, and Chadian insurgencies use Darfur areas for camps and training. These cross-frontier movements have led to charges by the Chadian government that the Sudanese government supports and finances the Chadian insurgencies while the Sudanese government charges that the Chadian government supports and arms the Darfur insurgencies. Both accusations may be true. Some commentators have seen an undeclared proxy war between Chad and Sudan.

In order to prevent cross-frontier armed movements and to protect refugees in Chad and in the northeastern zone of the Central African Republic, the European Union has agreed to send an armed observation-protection force – 4,300 are authorized – half of whose members would be French troops already stationed in Chad in accordance with a 1976 agreement. This plan will function under UN Security Council Resolution 1778 of 25 September 2007. Some 300 police officers under UN-command should join the European Union force (Eufor). Eufor, in addition to France, would have soldiers and police from Ireland, Sweden, Netherlands, Austria and Romania.

To make matters more complex, in addition to the Chad-Darfur cross-border alliances and rivalries, there is the Chad-Darfur-northeast Central African Republic insurgencies and the resulting displaced persons and refugees, an estimated 200,000 with 50,000 going to Chad. In northeast Central African Republic (Birao is the largest town of the area), there is an ongoing insurgency based on clans and former soldiers of the regular army. Again, these insurgencies have political names such as the Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (UFDR) and the Peoples’ Army for the restoration of the Republic and of Democracy (APRD). In addition to the destruction caused by the insurgencies, the Central African Republic’s regular army lacks discipline and often loots rather than bringing order to the troubled area.

The northeast is one of the poorest and most neglected areas of a poor and badly managed country. As with Darfur, the insurgencies are a misguided effort to attract governmental attention to real needs: health, education and economic development. Part of the European Union force will be placed in the northeast to limit the spillover effects of the Darfur and Chad conflicts. However, much more effective socio-economic efforts are needed to restore a sense of hope to the area.

For the moment, the fighting in Chad has delayed the deployment of this European Union force – some think that this delay was a major aim of the attack on Ndjamena. The UN-AU force in Darfur which was to have started in January is also slow getting off the ground. There is likely to be trouble for some time to come.

Rene Wadlow is the Representative to the United Nations, Geneva of the Association of World Citizens and the editor of the journal of world politics: www.transnational-perspectives.org

Photo by Mark Knobil, reprinted from Wikipedia under a Creative Commons License