The Black Alliance for Peace (BAP), along with partner organizations, held events April 4 in three countries across the Americas to launch an effort to activate popular movements in the region in support of a call for a “Zone of Peace.”

The Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) declared the Americas region a “Zone of Peace” in 2014. This came in response to centuries of oppression at the hands of Europe and, later, the United States. U.S. policy has related to Latin America and the Caribbean as the United States’ “backyard” ever since the Monroe Doctrine was announced in 1823.

“The U.S. declared the European states must stay out of the hemisphere, which meant the United States was claiming the entire region as its own,” said Margaret Kimberley, a BAP Coordinating Committee member, who spoke at a BAP press conference held April 4 in Washington, D.C. She added CELAC exists to counter the Organization of American States (OAS), a multilateral organization based in Washington, D.C., and known for backing U.S. policies in Latin America and the Caribbean.

After years of struggle and U.S. sanctions that have been linked to the deaths of 40,000 people in 2018, socialist-led Venezuela completed its withdrawal from the OAS in 2020. Meanwhile, another socialist country, Nicaragua, announced it was exiting in 2021.

“Biden says it is the ‘front yard’ in a clumsy attempt to be somewhat progressive,” Ajamu Baraka, chairperson of BAP’s Coordinating Committee, told Jacqueline Luqman and Sean Blackmon on the day after the launch, April 5, on “By Any Means Necessary,” an afternoon talk show on Radio Sputnik.

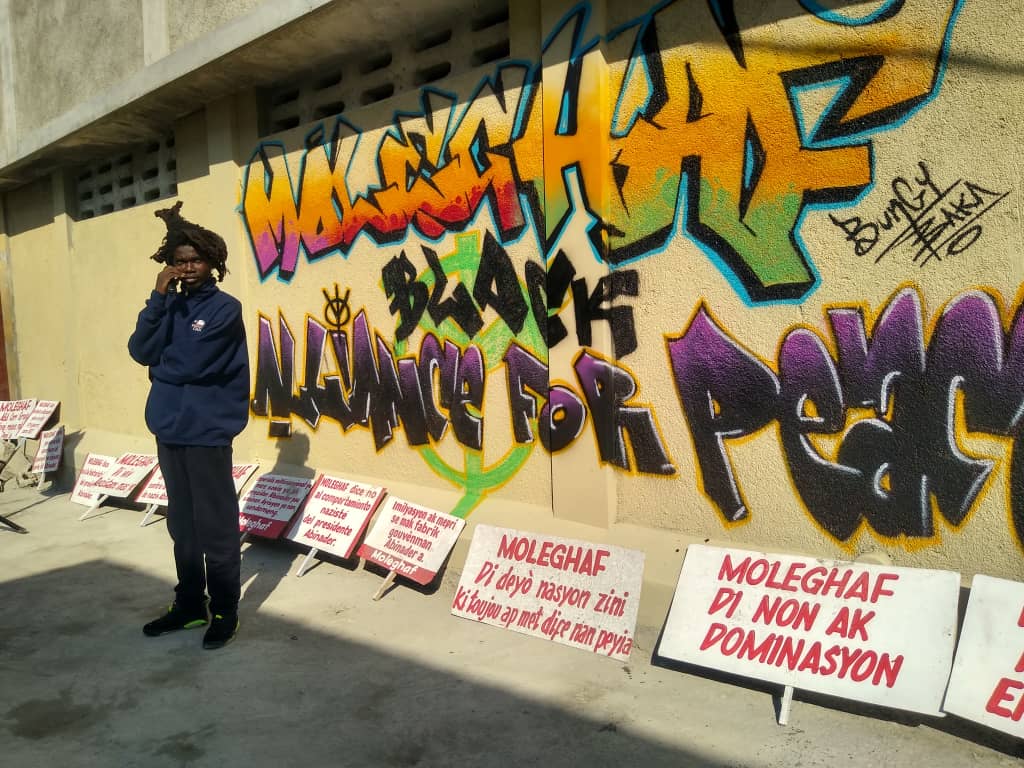

Launch events were held in Port-au-Prince, Haiti; Washington, D.C., USA; and in Havana, Cuba, where the call for a Zone of Peace was initially made in 2014. The event in Port-au-Prince involved eight hours of activities, ranging from performances, talks, exchanges, and graffiti and sign-making.

The launch took place on BAP’s 6th anniversary, which is the 55th anniversary of the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Exactly one year prior to his murder, King had publicly denounced the U.S. war on Vietnam, as well as what he identified as the three pillars of U.S. society: Materialism, militarism and racism.

“This campaign will be informed by the Black Radical Peace Tradition,” reads BAP’s press release. “With its focus on the structures and interests that generate war and state violence—colonialism, patriarchy, capitalism and all forms of imperialism—the fight for a Zone of Peace is an attempt to expel all of these nefarious forces from our region.”

BAP describes the reason behind the use of “Our Americas” on its website:

Nuestra América is a term revolutionary forces in the Americas have used to assert themselves against colonialism and imperialism by claiming one contiguous land mass stretching from Canada to Chile for all of the historically oppressed peoples of the region. BAP has translated the singular Nuestra América (Our America) into the plural “Our Americas” to help bridge the gap between the U.S. usage, “America,” that describes the United States as the only “America” and the concept put forth by revolutionary forces.

However, Baraka distinguished the campaign’s target.

“We’re not talking about the people of the U.S.,” he told “By Any Means Necessary.” “We’re talking about this settler-colonial state. We know [the United States] cannot exist as a settler-colonial state if it gave up its militarism.”

BAP also issued six “initial core demands”:

- Dismantle SOUTHCOM. Shut down the 76 U.S. military bases in the region

- End U.S./NATO military exercises. Close foreign military bases, installations and enclaves, as well as withdraw foreign occupation troops

- Disband U.S.-sponsored state terrorist training facilities. Shutter the “Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation” (WHINSEC)—formerly the School of the Americas—in Fort Benning, Georgia, United States, and terminate U.S.—as well as foreign—training of police forces

- Oppose military intervention into Haiti. Support the people(s)-centered movement for democracy and self-determination

- Return Guantánamo to Cuba. The United States must give back to the Cuban people and their government the territory it illegally occupies

- Sanctions are war. End illegal sanctions and blockades of regional states, including all economic warfare and lawfare, and recognize their sovereignty

Yet, BAP is clear the method for going about this work must be different than what has emerged from predominantly-white organizations based in the United States.

“This work must be de-colonial, anti-imperialist, advance a People(s)-Centered Human Rights (PCHRs) framework, and be conducted across at least five languages: English, Spanish, Portuguese, French and Haitian Creole,” BAP states on its website.

Jemima Pierre, co-coordinator of BAP’s Haiti/Americas Team, said at the press conference that the United States uses multi-lateral organizations like the OAS to oppress the peoples of the Americas. And, so, of the initial approximately 25 organizations that had signed onto the campaign before it had been launched, more than half are based outside the United States and Canada. Some of the partner organizations that will help coordinate the effort include:

- MOLEGHAF (Haiti)

- REDH (Network In Defense of Humanity) (Cuba)

- Caribbean Organisation for People’s Empowerment

- African People’s Socialist Party (Bahamas, Jamaica, United States)

- Proceso de Comunidades Negras (PCN) (Colombia)

- Asociación de Trabajadores del Campo (Nicaragua)

“Our homelands are not playgrounds for the U.S. to launch its wars of aggression,” said Nina Macapinlac, secretary general of BAYAN USA, an anti-imperialist alliance of 20 organizations dedicated to the liberation of the Philippines. Macapinlac spoke at the Washington, D.C., press conference as a member organization representative of the United National Antiwar Coalition, one of the organizations that BAP has partnered with for the Zone of Peace campaign.

BAP invites organizations and individuals to endorse the Zone of Peace campaign and activate the popular movement element in what they describe as a “multi-phase campaign that aims to build a united-front opposition to liberate our Americas from the U.S./EU/NATO Axis of Domination.” A U.S./NATO Out of the Americas Network will be launched as the mass-based structure of this campaign.

Julie Varughese is editor of Toward Freedom.