Editor’s Note: This article, originally published by Unbias the News, is part of the Sinking Cities Project, which covers six cities’ responses to sea-level rise. The investigation was developed with the support of Journalismfund.eu, European Cultural Foundation and the German Postcode Lottery.

It is the middle of July 2022. The downpour has been going on for four days with no signs of abating anytime soon. Cars are submerging into gaping canals. People are getting swept off the road and seven have died. Several houses are flooded.

The scenes are not uncommon during the rainy season for people living in Lagos, Nigeria; they were expected with millions of people living in densely populated suburbs without proper water channels.

Babatunde Noah, a cleric in his 30s, lives in a tenement bungalow on Odunfa street in Bariga, a low-income suburb in Lagos adjoining the Lagos lagoon. The rain has subsided that Tuesday morning, a slight relief. He is hoping it stops totally so that the single room he shares with his wife and only child can stop flooding. He is one of those who have not temporarily vacated their house in the community.

“I moved away from my former house because of the same problem,” Noah told Unbias The News. “In my former place, you dare not be away from home when it is raining. You will come back to see your room full of water.”

Noah said in the old and new places he has lived, every year, people mitigated the impact of the annual flood by cementing areas around the house and raising fences. But since 2018, when the Lagos state government under Akinwunmu Ambode filled Oworonshoki wetlands with sand, manufacturing an estimated 40 hectares (98 acres) of land to build a jetty terminal, the annual flood has defied this makeshift solution.

The National Emergency Management Agency says at least 8 million residents in Lagos are prone to flood disasters with 12 percent of the state subject to seasonal flooding, according to Lagos’ 2021 Climate Risk Assessment.

At the core of the problem is a clash of long overdue urban development and protection of natural ecosystems, a sprawling real estate industry, and a government unwilling to confront climate realities.

As the state’s population increases annually with thousands of people coming into the city every day, space becomes scarcer and the government’s idea of development, experts say, is infrastructure-centered.

‘Heading Towards a Catastrophe’

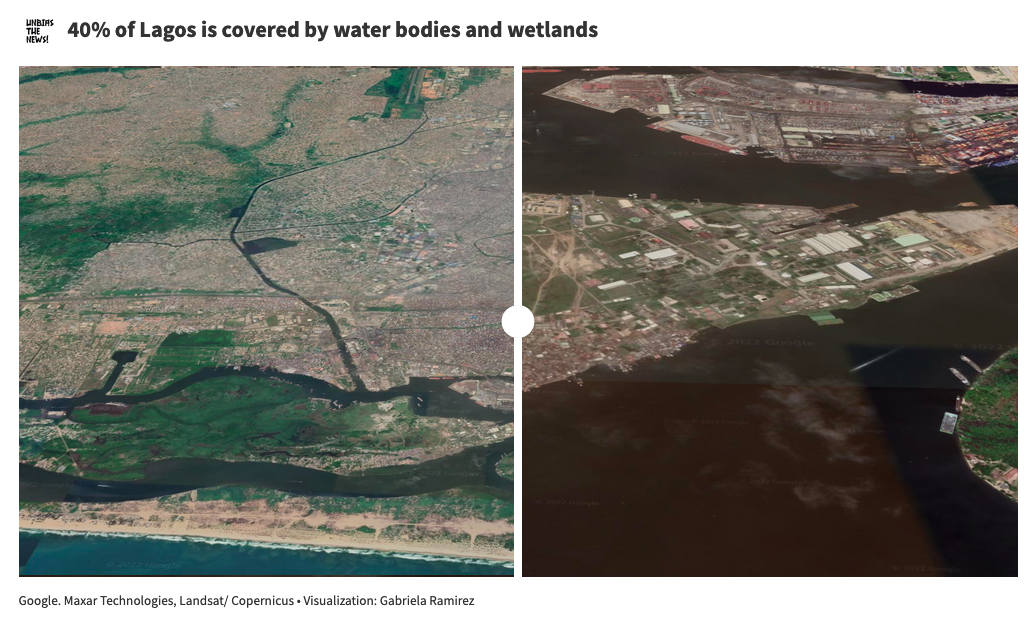

Lagos, Nigeria’s economic capital, is a low-lying coastal city and is just one meter above sea level. Its coastline accounts for 180 kilometers (111 miles) out of Nigeria’s total 850 kilometers (528 miles) stretch, positioning it as an important coastal economy. Forty percent of the state is covered by water bodies and wetlands.

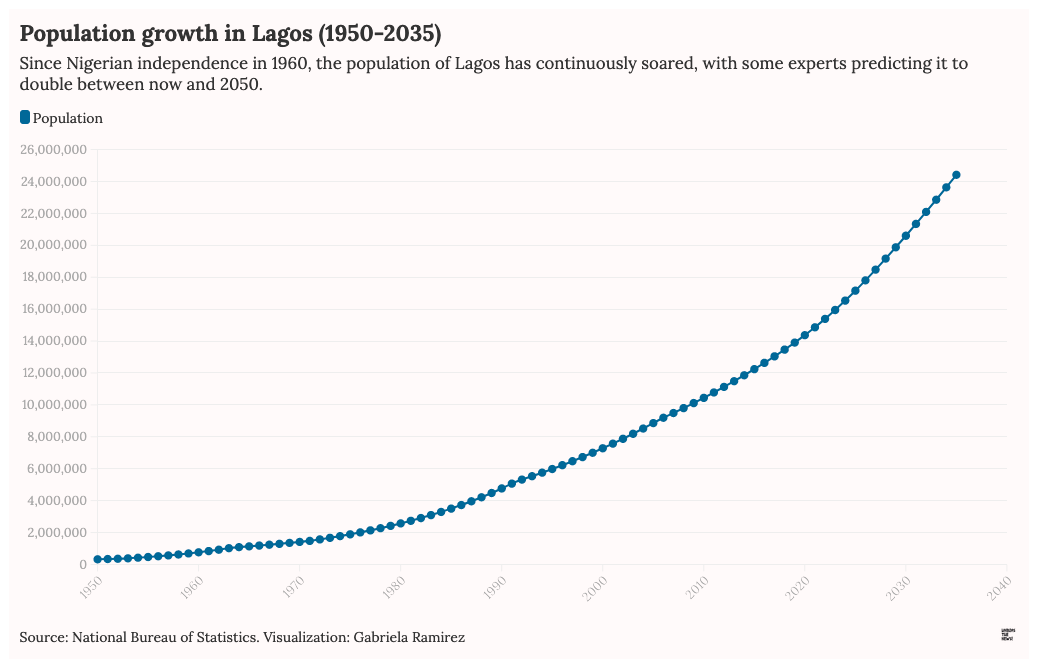

Lagos has grown from a tiny settlement of 28,000 people in the 19th century to a landmass of 3,345 km2 (2,078 square miles) with over 22 million people.

The expansion in size started with the British colonial government’s decision to transform Lagos into an industrialized trade centre in the 19th and 20th centuries to serve colonial interests. As a result, British colonizers made the first to foray into Lagos’ natural ecosystem to create residential estates and highbrow business districts. In a trend that has not diminished many decades after, thanks to an ever-increasing population and scarcity of space, successive Lagos state governments have continued to turn to the waterbody for land.

Experts and analysts say this portends danger as the city prepares–or not–for the projected sea level rise. The sea level rise is expected by two meters at the end of the century, putting Lagos, with its low topography, at the risk of completely sinking.

“We are heading towards a catastrophe,” Toyin Oshaniwa, the founder of Nature Cares Resource Centre, told Unbias The News.

“The question we should ask ourselves is: Are we really prepared for the greater risks that are coming? There is nothing we can do about it; as long we are here there is going to be flooding either from the coast shoreline or the rains that fall.”

As Lagos floods every rainy season, attention heightens around the city’s plan to tackle the challenge. Experts say the floods result from a lack of drainage services, vanishing green areas, an unorganized waste delivery system, and most importantly, vastly depleted wetlands.

“Lagos has not been properly planned to cater to its environmental component… The environmental challenges of Lagos seem too much to manage” Seyifunmi Adebote, an Abuja-based environmentalist said.

The population of Lagos residents is projected at over 32 million by 2050 and over 88 million by the end of the century, according to the Global Cities Institute at the University of Toronto, which would make it the world’s most populated city.

With an already limited space, environmental experts say they fear the urban population pressure would have grave consequences for the wetlands and the ecosystem.

“Looking at Lagos as it is today, it is inconceivable that 40 million people can be accommodated by 2050,” Adebote said. “With the horizontal infrastructural investments, every bit of environmental sanctuary will be ripped off. Personally, I believe 2050 is even too far to use as a yardstick for the urgency of action Lagos state needs to take to respond to its fast-degrading environmental status.”

Wetlands Sold Off to the Highest Bidder

According to experts, Lagos is one of the cities which will be most affected by the sea-level rise which will now be expected to inevitably rise by a minimum of 27 centimeters (10.6 inches) as a result of the melting Greenland ice cap, projected to bring 110 trillion tons of ice into the sea. As global temperature rises as a result of the sustained burning of fossil fuel, glacial ice, iceberg and ice shelves are melting away.

Pristine wetlands, environmentalists say, will help Lagos mitigate some of the now-inevitable consequences of global warming. But the wetlands are at the risk of extinction in time for the projected timeframe for sea-level rise.

No one knows the exact numbers of wetlands left or the rate at which they have been encroached by developers, not even the government itself, but the consensus among experts and the government is that half of them are gone.

Wetlands are critical to the ecosystem as they serve various functions ranging from being home to biodiversity, recharging underground water, controlling shoreline erosion and preventing flooding. These wetlands can contain rain and store them for underground recharge. As wetlands diminish in Lagos and the intensity of rain increases due to climate change, the natural ‘’sponge’’ retaining water is no longer in sight.

But the roots of the problem date back to the 1970s when the United Nations organized a multilateral framework to protect wetlands. The convention recognizes 11 wetlands in Nigeria, brought under international protection, excluding Lagos.

The government of the day did not provide the documents for Lagos; until today, the Ramsar List does not recognize Lagos’ wetlands.

“I believe it is one of the reasons they are not really protected,” Oshaniwa said.

In 2016, the state government drafted a policy to protect the wetlands. The draft policy recognized 31 wetlands and was reviewed in 2017 at a stakeholder’s meeting.

The policy has not been made law to date. Later on, according to Tolulope Adeyo, the director of the Department of Conservation and Ecology in the state’s Ministry of the Environment, the agency outsourced the surveying to a private company because the draft policy was not “comprehensive.”

In the meantime, Adeyo told Unbias The News that the department has embarked on advocacy programs across the state and constituted a monitoring team to ensure that the locals do not encroach on wetlands.

“People are looking at the economic worth of these wetlands and not the environmental importance,’’ Adeyo said, adding that they have had to enforce stoppage of constructions and seizure of property.

Some civil society organizations say that the government grants permits to real estate developers to provide exclusive highbrow residential areas and use them to build public infrastructure, bringing billions of naira in internall generated revenue to the state coffers.

The Ministry of Physical Planning and Urban Development–corroborated by two other sources within the Ministry of the Environment who requested not to remain anonymous for fear of punishment–is responsible for allocating wetlands to real estate developers.

“The Ministry of Environment seems to be interested,” Olamide Udomo-Ejorh, director of Lagos Urban Initiative Development, a non-governmental organization campaigning for the protection of wetlands told Unbias The News. ‘’When we went for meetings they said wetland protection is something they really want to look into, however, the Ministry of Physical Planning is still giving it out to be built upon.’’

“That inter-agency lack of synergy is a challenge,” Oshaniwa, who is an expert regularly consulted by the Ministry of Environment and has worked with the ministry for more than a decade, also said of the issue. “There is a lack of that long-term planning and [we have] this policy somersaulting, everybody comes with one thing [or another].”

Adeyo declined to speak on the matter, but an NGO working closely with the Lagos government that does not want a mention in this story confirmed to Unbias The News.

The ministry of physical planning and urban development did not respond to requests for comment on the lack of inter-agency cooperation.

A Lack of Political Will

Lagos state is a member of C40 Cities, a global network of governors and mayors working together to adapt their cities to the impacts of climate change, tailored to achieve the Paris Agreement and committing to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. In collaboration with C40, the Lagos state government has developed a Climate Action Plan, which outlines plans for the state to achieve its climate goals. The second installment, which runs from 2020-25, does not include a plan for wetlands protection, nor is a mention of wetland protection in the Lagos Environmental Management Law 2017 (as amended).

When asked if it is possible to restore the reclaimed wetlands and stop further encroachment, Maximus Ugwuoke, the Lagos city advisor for C40, puts it to “political will.”

‘’It depends on the political commitment of the government in power,” Ugwuoke said. “The way I see it is that if care is not taken, the masses are going to the streets if we don’t start taking action about wetlands. People have reclaimed wetlands and water is entering people’s homes.’’

As in most cases with environmental issues, the diminishment of wetlands is not a topic on the front burner. It remains a topic mostly examined in conferences, stakeholder meetings and seminars and the general population does not have the full scope of the damage already carried out, both by the government, which rather places economics above the environment and people trying to find a place to live in the city.

Unbias The News examined some critical wetlands in Lagos using satellite imageries and the extent to which they have been encroached on in the past decades.

The wetlands investigated by Unbias The News are Omu Creek wetlands, Akoka wetlands, Ajah wetlands, Ikorodu South wetlands, Badagry Creek and Lekki Conservation wetlands. The years vary but we were able to trace the progression of depletion in the past two decades.

Satellite investigation reveals that Omu Creek, located in Eti Osa local government bordering the Lagos lagoon and the Atlantic Ocean, is home to the tropical Mangrove swamp wetlands vegetation (common in the Southern part of Nigeria) that showed uncommon resilience over the decades. Between 2002 and 2005, the creek’s most flourishing years in the century as evidenced by multiple satellite data, over 80 percent of its natural marshland floors were intact.

However, in the 2010s, as communities started to grow around the creek the wetlands began to diminish. Satellite images below show the gradual expansion of development. By 2021, 37 percent of the wetlands have been lost.

Similarly, other remaining major wetlands have diminished. Wetlands in Akoka, a suburb of Yaba, a community seen as the social transition between Lagos Mainland and Lagos Island, have diminished by 19 percent between 2013 and 2022. In Ajah, an affluent area of Lagos Island, the wetlands diminished by 19 percent between 2012 and 2021. The wetlands in Ikorodu South, located in the northeast part of the state and sharing boundary with Ogun state, did the same number between 2011 and 2022.

Wetlands in the Badagry Creeks, a border coastal town which was used for the trans-Atlantic slave trade, diminished by 29 percent between 2013 and 2021. The most alarming instance is Lekki Conservation Centre wetlands which diminished by 42 percent between 2011 and last year.

‘Like a Tsunami’

Adewunmi Ishola, a roadside food seller who retails cooked staple foods like rice and beans, had lived in Itodun town, a coastal community at Ibeju Lekki, with her three children for years. The house in which she was living, just like Noah’s, was a tenement house, typical for low-income earners in Lagos, where many families share the same facilities like a kitchen and toilets.

Several houses separated the building, a plantation of coconut trees that stretched some meters, which was a cynosure for foreign tourists and local beach lovers and then a beach on the Atlantic Ocean.

But the coast is eroding, and as the community kept a months-long vigil over their houses, it was only a countdown. The beach gradually wore away, the whole coconut plantation. As seen by Unbias The News satellite images, the coastline in Itodun eroded by 48 meters (157 feet) between 2020 and 2021 alone.

Since 2020, a forceful surge has been threatening the community. By August 2021, it got to the houses. One midnight in that fateful month, it washed some houses away as Ishola, and her children awoke to screams and rumbles of people trying to salvage their property. By morning, houses were gone, livelihoods drowned, and decades-long corpses of buried people resurfaced.

“I watched the Tsunami, it was just like that,” Ishola narrated, referencing a once viral CGI-animated end-of-time ocean surge that washed off an entire city. ‘’I was so scared, people were all screaming. Nobody affected could get a thing out,” she recounted.

In a blink of an eye, not unexpected, hundreds of people are robbed of homes and life savings. ‘’This place is not where someone should live… It is the economic situation. It is too close to the ocean,’’ Ishola berated.

‘’It is loans we survive on. A year’s journey has been turned into a decade, even in a decade, I can only hope to God we get there,’’ she said when asked how they are recovering from their losses.

Lagos’ shoreline has battled erosion for decades, and the acceleration, which has alarmed experts and environmentalists, is driven by climate change and human activities. Lagos’ coastline is also the site of some of the state’s most ambitious infrastructures, hoping to position the city as a major global economic force.

But as these developments continue, low-income coastal communities are already feeling the impacts. In Ibeju Lekki, a well-too-known portrait of Lagos is rapidly shaping up – urban development coming at the expense of the urban poor. As erosion eats deeper into their communities, thousands of livelihoods and ancestries will be displaced within an already congested city, pushing them off the map.

Deflecting the Problem

Idotun is one of the numerous clusters of communities in Ibeju Lekki and has been there for centuries. The Lekki Free Trade Zone—a 16,500 hectares (40,772 acres) area with a coast border of about 50 kilometers (31 miles)—was created in 2006. Given its GDP and growth prospects, Lagos is conceived to be West Africa’s principal economic hub. It includes, among several other companies, a refinery by Africa’s richest man, Aliko Dangote and a new $1.5 billion port, Nigeria’s deepest.

The ongoing construction of the port has created conditions for erosion by redirecting stronger waves towards the community’s portion of the coast. To protect the port, barriers have been erected to withstand surges and make it formidable against erosion, much like the famous ‘’Great Wall of Lagos,” an 8.5 kilometer (5.28 mile) wall covering Eko Atlantic, an upscale artificial city built on reclaimed land on the Atlantic Ocean at Victoria Island.

The protective walls deflect the wave downstream, experts say.

“It is alarming,” Dr Olusegun Adeaga, a lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Lagos said of the rate of erosion on Lagos coastline. ”There will be deposits somewhere and there will be erosion in other places. [Ocean waves] will deflect back and erosion is the implication. Unless those natural barriers [wetlands and mangroves] are back or you mimic nature to believe those structures are there. If not, as you save one, you lose one.’’

Lekki Free Trade Zone Development and Eko Atlantic did not respond to requests for comments. Nor did the Federal Government, the principals of these projects.

Coastline Erosion at Alpha Beach and Idotun

Unbias The News examines erosion at the coastline in two communities with the most extensive coastline development.

As shown in the satellite images below, the coastlines of Idotun and Alpha Beach communities have receded heavily in the past five years. The Idotun coastline has eroded by at least 80 meters (262 feet) in less than five years, wiping off hundreds of houses and other structures. Within 2018 and 2020, it extended inland by 48 meters (157 feet) and between 2020 and the following, 32 meters (104 feet) were recovered through the massive sand filling. which residents told Unbias the News most of it has been lost again due to erosion. Investigation shows that most of the erosion happened in the last five years, coinciding with the most extensive development of the port.

Also, Alpha Beach has eroded 87 meters (285 feet) between 2016 and 2022 and destroyed at least 120 coast buildings and structures according to satellite investigation since 2017 and displacing hundreds of low-income families.

Satellites showed significant advances between February 2018 and December 2018, an 11-month period with a record of about 60 structures loss due to water-induced soil degradation, and by 2021, the number had doubled.

Some developments sprang up laterally on the flanks, where residents away from the coast to develop lands adjacent to the advancing water, seemingly buying more time before the land was taken over by the rapidly advancing coastal boundary.

With an eroding coast, now an inevitable sea level rise and continued loss of wetlands which studies say in normal circumstances can keep up with the rise in sea level but due to climate change and the expected high-level rise, Lagos has become extremely vulnerable.

The National Emergency Management Agency, the agency responsible for managing disasters in Nigeria and which will be responsible for managing possible outcomes of devastating flooding, said it cannot predict the future but has a stockpile of relief materials for two weeks in the case of any eventuality.

‘’Every time, the situation is dynamic and based on needs,’’ Farinloye Ibrahim, the Coordinator for Lagos Territorial Office for the agency said. “We have two weeks’ stock of relief materials depending on the local government.”

Already, more than 600 people have been killed and 1.4 million others displaced this year alone as a result of flooding in almost half of the country which was sparked by heavy rainfalls and lack of critical infrastructure and it remains to be seen the true capacity of the agency as hundreds of thousands of people more are displaced.

The 2.3 million people affected in Nigeria by the ongoing flood will disagree with the availability of relief material.

Requests for comment from the government were received, but not responded to.

As the world prepares for a rise in sea level which will facilitate increased coastal flooding, Lagos state government’s increased vigor for developments and licensing of exclusive real estate at the expense of environmental concerns is a source of great worry to analysts.

Lagos has become one of the most expensive real estate markets on the continent thanks to its increasing commercial values and expanding multi-billion dollar GDP but the growth is papering over the cracks. As the economy expands and luxury estates rise, the foundation weakens and is ready to sink.

In its 2021 climate risk assessment, the Lagos state government acknowledges that 12.9 million residents are vulnerable to climate impacts, representing almost half of the current population and more would be affected as population increases.

Besides the possible loss of lives, an estimated $4 billion are lost to flooding every year, which is 4.1 percent of the state’s gross domestic product. In August 2022, the state governor pledged a 20 billion naira Green Fund Initiative to tackle the impact of climate change.

The biggest hurdle, civil society is saying, is the government and policymakers.

‘’For the policymakers in Lagos, I think for them [the issue of climate change] is still an academic exercise. Let’s do a resilience strategy, they do it. Let’s do a surge prevention study, they do it. Let’s do a Climate Action Plan, they do it. They are not seen as a real-life issues.’

“The coming election, that is the same promise they will make to us. They will say they will do the road and channel the gutters but that is their promise every year. We are tired but we don’t have any other option. We don’t have any other place to go. If we are to get an apartment where water does not disturb us, it is quite expensive,” Babatunde said.

People like Adewunmi and Babatunde do not have knowledge of the science changing around them and there is barely anything they can do. But they are on the frontline of a dangerously metamorphosing city.

Mansir Muhammed contributed satellite image analysis for this story.

Ope Adetayo is a freelance journalist based in Lagos, Nigeria. His works have appeared in Al Jazeera, The Guardian UK, Foreign Policy, Vice, The Africa Report and African Arguments, among several others.