Every year on July 2, the extended family of 67-year-old Dhati Kennedy gathers on the banks of the Mississippi River to pray, sing and place a memorial wreath in the muddy waters.

“My father’s people came up from the South looking for a better life,” Kennedy told Toward Freedom. “But the perceived advancement of Black people at that time was often met with violence—and state sanctioned violence.”

About 60 family members clad in white join Kennedy every year to honor their grandfather, who died a hero defending the family from a pogrom waged by thousands of white people who swarmed Black neighborhoods on that day in 1917 in East Saint Louis, a riverfront city in Illinois. They also mourn and celebrate their grandmother, who helped pilot the family’s makeshift raft across the river to the larger city of Saint Louis in Missouri. This feat came after police closed the Eads Bridge, in what has been viewed as a way to prevent East Saint Louis’ Black residents from escaping. His grandmother was a widow for just a few weeks, though, before dying of pneumonia.

Escaping White Terror

Kennedy’s father, Samuel, was 7 years old when he and his siblings hung onto a vessel made out of doors ripped from their hinges. Having heard screams and gunshots, Kennedy’s teenage brothers scrambled to build the raft the family used to escape. Many witness accounts reported white gunmen setting ablaze the homes of Black families and shooting them as they fled the inferno with children in their arms.

Earlier in the day, Kennedy’s grandfather lost his life after luring six of the white killers away from his wife and children. He killed two of the attackers before the others murdered him.

“We give thanks to God and to our ancestors. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be here now. We pour libations and say, ‘Ashé,’” Kennedy said, describing the African spiritual act of pouring liquid that has been blessed to honor ancestors. Ashé is a Yoruba concept that originated in what is now Nigeria. It is used to describe the force of the universe. To some, it can mean, “So be it.”

Little-Known History’s Impact

It’s a heavy legacy, one that Kennedy tries to wear as lightly as possible, so he can persevere in his lifelong mission to spread knowledge about this history.

The descendants and their supporters’ efforts reached a pinnacle in 2017, the massacre’s centenary year. Interviews and articles abounded in local, national and international media. Plus, ceremonies culminated in a march featuring thousands of people from both sides of the river.

Yet, five years later, the East Saint Louis Race Massacre is still not taught in the Illinois public-school history curriculum. Neither are the histories of similar atrocities that killed Black people and destroyed homes and businesses in other cities in Illinois, such as Evanston, Springfield and Chicago.

“We know that what happened in 1917 had an impact on this region economically, politically, socially, demographically—and had a huge impact psychologically,” Kennedy explained. “If you truly want to end racism, let’s tell the truth. Let’s get it all out there. Prejudice from individuals? That’s not the thing. It’s the systemic stuff holding us down that hurts us most.”

What Led to the Race Massacre

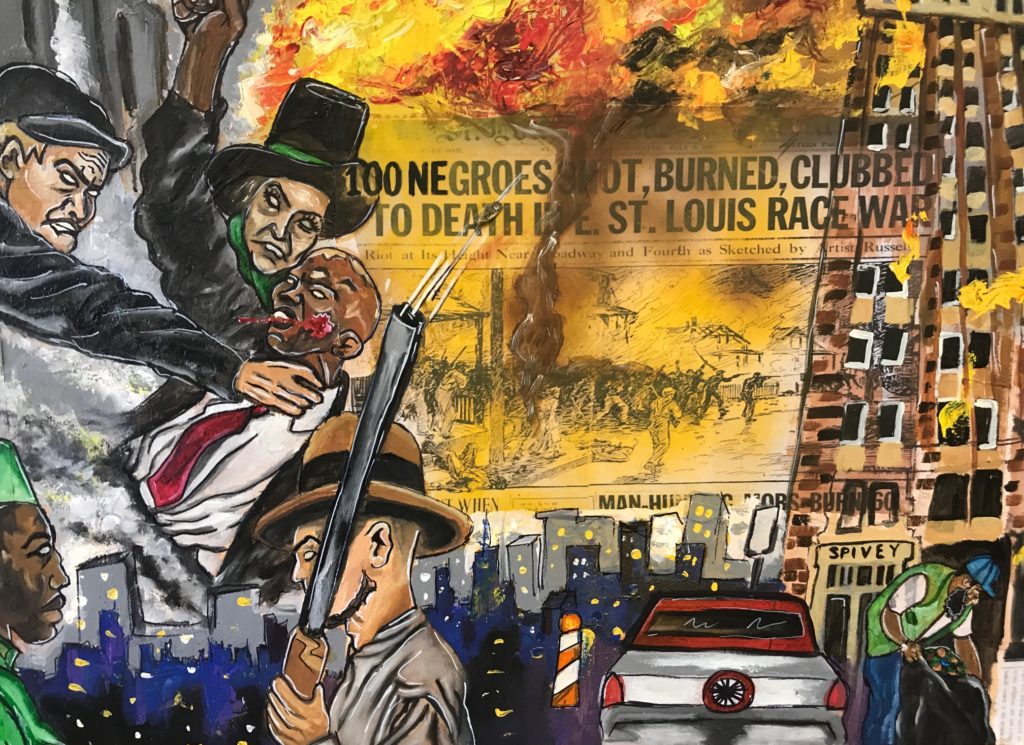

In the days preceding the 1917 race massacre, striking white workers from Aluminum Ore Company were out patrolling Black neighborhoods in a Ford Model-T car, firing potshots at Black workers, who—with few other options for employment—had been hired to replace them. Wage-seeking white men had become scabs, too. But the strikers terrorized the Black community. The East St. Louis Daily Journal, a local newspaper, had also run a series vilifying Black people migrating from southern states, calling them “Black colonizers” and blaming them for a crime wave. In May 1917, the paper had on several occasions claimed to predict future race riots, according to historian Charles L. Lumpkins.

The community was not completely defenseless, however, as some of the local Black men had served in World War I. While they didn’t have big armaments, they could stand guard outside their houses and shoot back with their squirrel-hunting rifles. Some were crack shots. On July 1, when two such Black defenders aimed fire at two white men in a Model-T they’d assumed had come gunning for Black workers, they accidentally killed two undercover police officers driving an unmarked car.

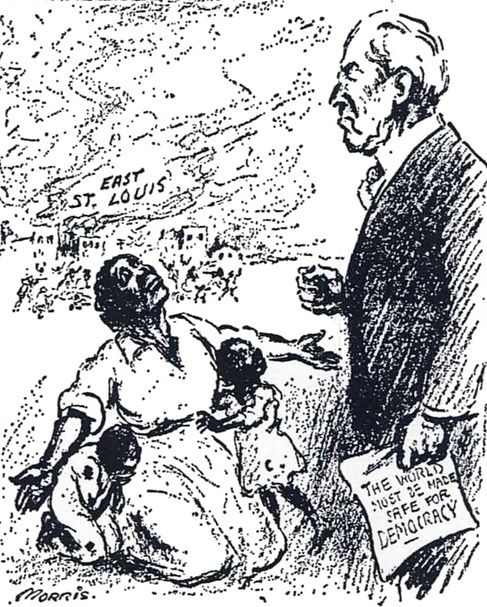

The next day, the duo’s error unleashed a mob of thousands of white people. In the end, more than 100 Black residents were slaughtered. Black adults and children reportedly had been beheaded, burned alive and drowned. Some were beaten with clubs and stones, while others were hung from street lamps. This came while officials either turned a blind eye or made matters worse by—for example—closing the main route of escape.

An estimated $400,000 worth of homes and businesses were destroyed. That would amount to $9.6 million today. The destruction displaced an estimated 6,000 Black East Saint Louisans.

“Much of the neighborhood where my father lived is vacant lots now,” Kennedy said. “Just acres and acres of vacant lots.”

A snapshot 105 years later leads to a tally of compounding losses: The East Saint Louis economy is limping along while the landscape remains blighted. Its population shrunk by 58 percent from 60,000 people in 1917 to 25,000 people in 2020. Plus, almost a third of its overwhelmingly Black residents live beneath the federal poverty line.

“It’s the wealthy who benefit from the turmoil that everyone else is in,” Kennedy said.

The Role of Reparations

Jeffrey “JD” Dixon is director of Empire 13, a grassroots activist organization originally formed to combat racial discrimination at Empire Comfort Systems, a nearby manufacturer. Then we have the Rev. Dr. Larita Rice Barnes of Metro East Organizing Coalition, a faith-based grassroots organization working for racial and economic dignity. Both organizations form part of a coalition building a political program from the ashes of the 1917 massacre. They believe the community deserves recompense for the cruelty and crimes that smashed the city like an insect, but never eradicated its heart.

“East Saint Louis is a city that’s so full of love that—no matter where you go—even to the gang bangers, which we have, there’s a spot of love,” Barnes said. “And even though [the] media has amped up a lot of negativity, we are striving to tell our own story, and share the truth about our people. We are known as the City of Champions.”

She’s referring to jazz composer Miles Davis; choreographer Katherine Dunham; and R&B legends Ike and Tina Turner. They had either been raised in the city or lived there. That’s not to mention a slew of athletes, including Major League Baseball players.

“We need economic relief and economic justice,” Dixon said. “America is an economic powerhouse because of slave labor, because of systemic economic oppression of Black labor—be it from lower wages, mass incarceration, icing us out of government contracts. Our Black communities have a Third-World country status, and we’re treated like second-class citizens.”

Dixon is still incensed Black residents of East Saint Louis could not cover damages through their property insurance policies because insurers said they needed riot insurance.

“There was no accountability for the hundreds of lives that were lost or for the millions of dollars of properties destroyed, the generational wealth lost from businesses and homes that could’ve been passed down to the next generation,” Dixon said. “Some of those businesses could’ve been Fortune 500 companies.”

What Justice Might Look Like

Barnes and Dixon’s program stresses new ways to redirect public resources to the communities that have suffered the most systemic economic oppression. That could include direct payments, business and home loans on advantageous terms, grants, restoration of felon rights, and state legislation against race-based discrimination.

To commemorate the massacre, the group held a march through the old Black neighborhoods. Once teeming with homes and businesses, it is now an urban landscape of vacant lots. In an attempt to reclaim the streets and unite the past with the present with every step and chant, a few dozen marchers who braved the pouring rain on Saturday called out: “We are the people. The mighty, mighty people. Fighting for justice. Justice for the people.”

Barnes has considered that race-based reparations can cause resentment, and that an alternative course to improve the material conditions of Black people may be to lift up the multi-racial working class. But she is concerned about Black people who languish in poverty, beneath the working class.

“I believe in lifting from the bottom up, and reaching those closest to the pain,” she explained. “Working class-based reparations would fail to reach some people, and we can’t build successfully by leaving people behind.”

Barnes brought the struggle for reparations back to the memory of their ancestors.

“It was something that they wanted and couldn’t achieve,” she said. “But perhaps we can.”

Frances Madeson writes about liberation struggles and the arts that inspire them. She is the author of the comic political novel, Cooperative Village. Follow her on Twitter at @FrancesMadeson.