Around 200 million industrial workers, employees, farmers and agricultural laborers observed a two-day general strike in India on March 28 and 29. The strike was working people’s challenge to the far-right government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. This video was created by People’s Dispatch.

Related Articles

Related Articles

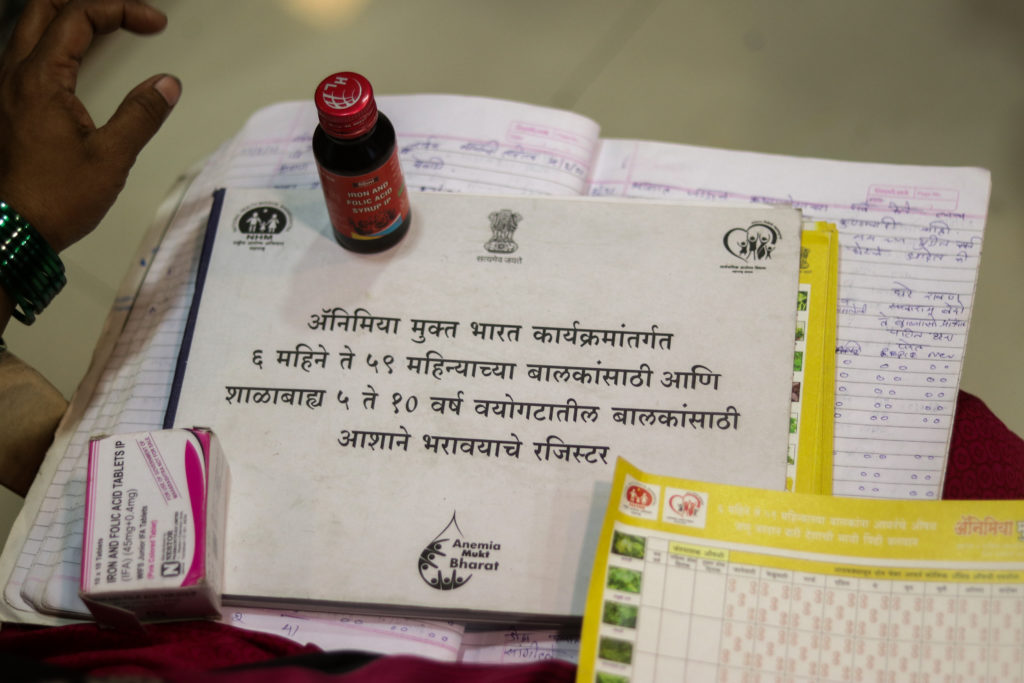

Photo Essay: India’s Rural Health Workers Fell Ill As Workload Spiked During Pandemic

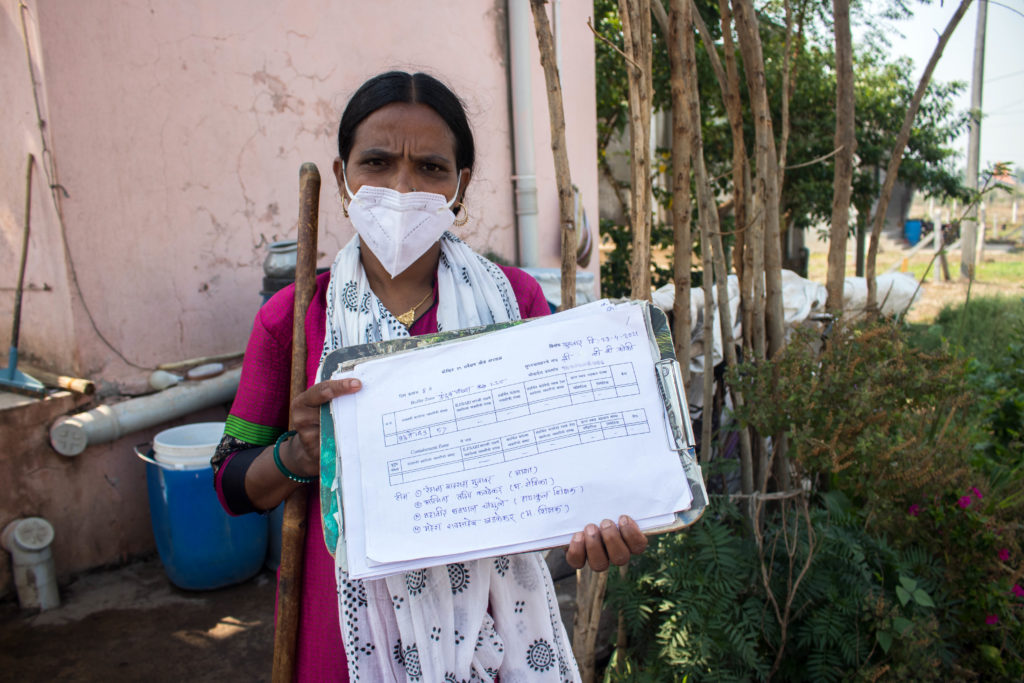

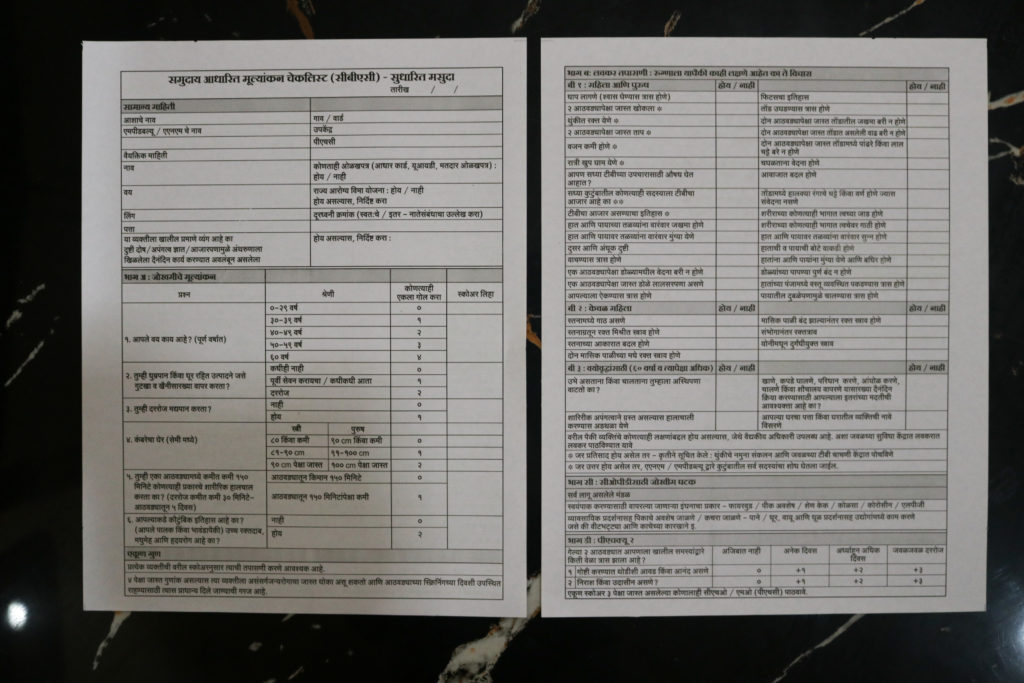

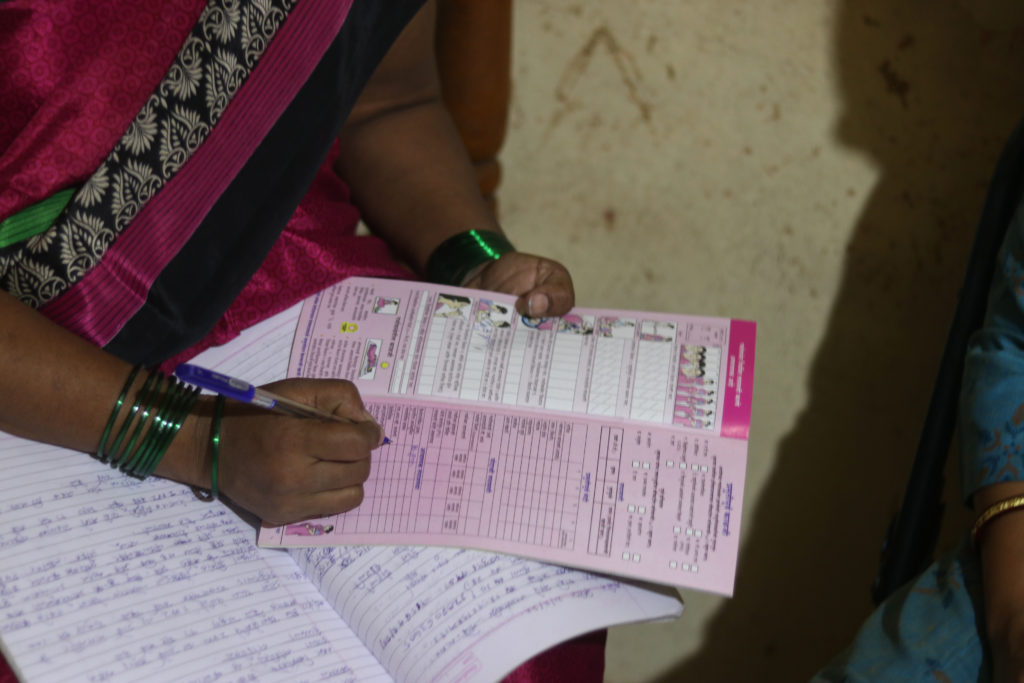

Prajakta Khade walked into a public health center daily for three months in early 2021, without ever receiving medical care. The healthcare worker’s 26 notebooks—containing more than 3,000 pages of community health records—point to why she couldn’t seek treatment for her ailments. She was simply too busy.

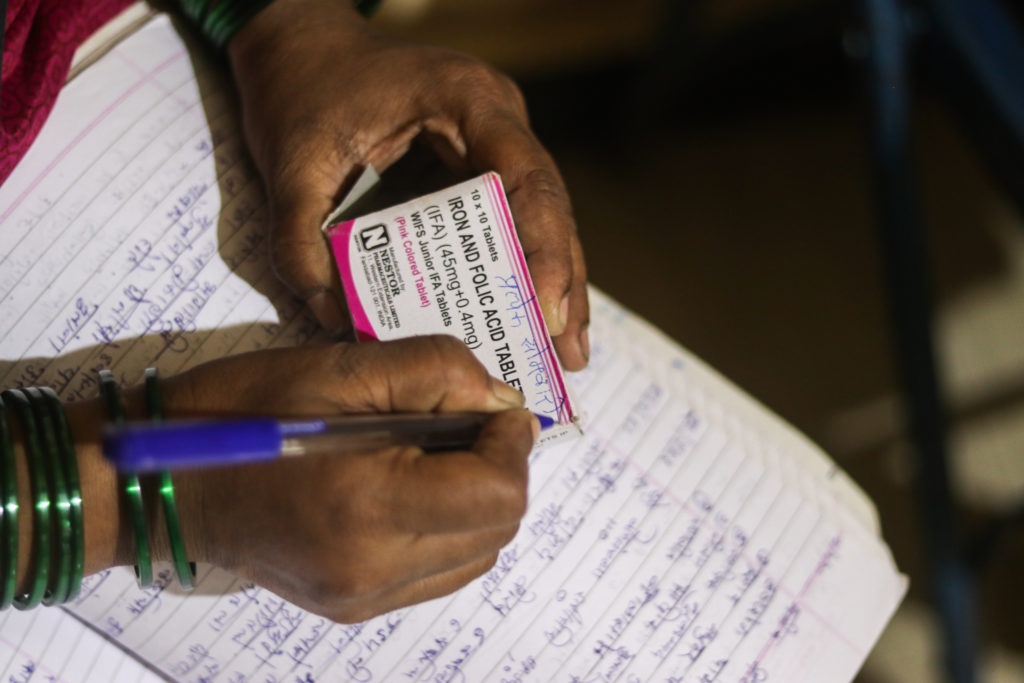

In March 2020, India’s health ministry tasked 1 million Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) like Khade with COVID-19 duty in rural areas. This, in a country where 65 percent of its 1.38 billion people live outside cities. Suddenly, ASHAs’ workload increased exponentially. Yet, they remain underpaid and now suffer stress-related chronic ailments.

“If a positive case was found in the area, we had to visit the patient, contact trace, arrange medical facilities, measure their oxygen and temperature levels daily, and ensure they complete quarantine,” Khade explained about the added duties to treat the infectious respiratory disease. But all Khade was given to do her job in the assigned area in India’s Maharashtra state was a single N95 mask and 200 milliliters of sanitizer.

ASHAs, an all-women healthcare cadre, remain the foot soldiers of India’s rural healthcare. One worker is appointed for every 1,000 citizens under India’s 2005 National Rural Health Mission. ASHAs are responsible for more than 70 tasks, including providing first-contact healthcare, counsel regarding birth preparedness, and pre- and post-natal care. Plus, they help the population access public healthcare and ensure universal immunization, among other things.

The World Health Organization announced a pandemic in March 2020. But in many countries, lack of adequate healthcare and no social safety nets amid lockdowns wrecked the lives of ordinary people. In India, for example, an additional 150 million to 199 million people are expected to enter poverty in 2021 and 2022.

Chronic Illnesses Spike

One day about a year ago, while surveying people in her village of Vhannur in India’s Maharashtra state, 40-year-old Khade felt dizzy. But she couldn’t take a break. “At one point, my face was swollen, and I could barely see anything.” It turned out her blood pressure level had surged to 252/180 mmHg (millimeter of Mercury), much higher than the standard limit of 120/80. That is how she got diagnosed with hypertension.

However, a month’s worth of medications didn’t help because she continued to experience stress as her workload increased. Senior officials at the health center had early on issued an order to submit patient records daily by noon.

ASHAs, who aren’t considered full-time workers, receive performance-based incentives paid on the number of tasks completed. “For COVID duty, the government decided our worth as merely 33 Indian Rupees per day (43 U.S. cents),” she said. “We received this amount only for three months in the past two years.”

Moreover, during the peak of COVID-19 cases in 2021, salaries for Maharashtra’s ASHAs were delayed by five months, according to Khade. Netradipa Patil, an ASHA from Maharashtra’s Kolhapur district and leader of a union that represents more than 3,000 ASHAs, confirmed this.

One day last year, Khade’s supervisor asked for a list of hypertension and diabetes patients from her village of about 1,200 people—at 10 o’clock at night.

“How could I survey the entire community in the night?” she asked.

Often, such orders meant skipping lunch and staying hungry for 11 hours at a stretch. ASHAs worked four hours prior to the pandemic. Now, 12-hour days are normal.

When medications didn’t help, Khade consulted two private doctors. “After six months of hassle, the doctor doubled my dose to 50 milligrams.” Khade lost over 10 kilograms (22 pounds) of weight and was placed on medications to address anxiety. Even today, she suffers from fatigue.

“I was never this weak,” she asserted.

Chronic diseases among ASHAs are rising rapidly because of the workload, says Patil. “We protect the entire community, but there’s no one to look after our health.” ASHAs in Maharashtra, she says, average a monthly income of Rs 3,500 to 5,000 ($45 to $66 USD).

This reporter spoke to ASHAs’ senior officials from Maharashtra’s Kagal block. (In India, a cluster of villages form a block and several blocks form a district. Vhannur village is in the Kagal block of Maharashtra’s Kolhapur district.) Senior officials said they are not responsible for ASHAs’ deteriorating mental and physical health, and pointed to the Indian government’s order to submit data. The officials didn’t want to be named. Instead, they relayed that they also are overworked.

“ASHAs do the majority of the health department’s work, and they are massively underpaid for their duty,” said Dr. Jessica Andrews, a medical officer at Kolhapur’s Shiroli Primary Health Center. She has been handling mental health cases. “Without them, the health system will collapse.”

‘Not Treated As Humans’

Several ASHAs across India have worked for over a year without a break. One of them is Pushpavati Sutar, 46, diagnosed with hypotension (low blood pressure) and diabetes within seven months of COVID-19 duty in November 2020. Like Khade, she experienced constant spells of dizziness.

“Often, there was fake news of community COVID transmission in my area,” she said.

Every day, senior officials at the health center hounded her to find more details about such instances.

An ASHA for 13 years, she’s never made an error in her surveys and was sure of no community transmission. “After investigating, I found that the accused was COVID negative. Instead, two of his relatives were positive.”

She had to clear such misconceptions almost every day, answer senior officials’ questions, collect records and perform her regular duty. “For several days, I couldn’t sleep,” she remembered.

Further, fearing COVID-19 guidelines and quarantine rules, community members began demanding ASHAs hide COVID-19 cases. “People even accused us of spreading COVID as we would survey the entire village,” Sutar recounted. Moreover, she said senior officials asked ASHAs to visit the families of COVID-19 patients—instead of allowing data collection over the phone—putting them at risk of infection.

“At several places, there have been instances of community violence, where ASHAs were beaten up,” said Patil, who has filed legal complaints on behalf of the assaulted workers and is helping them mentally recover.

Kolhapur’s ASHA union has written to several government authorities, including Maharashtra’s chief minister and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, highlighting the mental toll of COVID-19 duty. Still, none of their letters have garnered a helpful response.

“Forget adequate pay,” said Khade, as she continued surveying, juggling between completing her task and trying to keep her mind at ease. “We are not even treated as humans.”

Sanket Jain is an independent journalist based in the Kolhapur district of the western Indian state of Maharashtra. He was a 2019 People’s Archive of Rural India fellow, for which he documented vanishing art forms in the Indian countryside. He has written for Baffler, Progressive Magazine, Counterpunch, Byline Times, The National, Popula, Media Co-op, Indian Express and several other publications.

What Does India Get Out of Being Part of ‘The Quad’?

Editor’s Note: The following analysis was produced in partnership by Newsclick and Globetrotter.

The recent Quad leaders meeting in the White House on September 24 appears to have shifted focus away from its original framing as a security dialogue between four countries, the United States, India, Japan and Australia. Instead, the United States seems to be moving much closer to Australia as a strategic partner and providing it with nuclear submarines.

Supplying Australia with U.S. nuclear submarines that use bomb-grade uranium can violate the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) protocols. Considering that the United States wants Iran not to enrich uranium beyond 3.67 percent, this is blowing a big hole in its so-called rule-based international order—unless we all agree that the rule-based international order is essentially the United States and its allies making up all the rules.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had initiated the idea of the Quad in 2007 as a security dialogue. In the statement issued after the first formal meeting of the Quad countries dated March 12, 2021, “security” was used in the sense of strategic security. Before the recent meeting of the Quad, both the United States and the Indian sides denied that it was a military alliance, even though the Quad countries conduct joint naval exercises—the Malabar exercises—and have signed various military agreements. The September 24 Quad joint statement focuses more on other “security” issues: health security, supply chain and cybersecurity.

Has India decided that it still needs to retain strategic autonomy even if it has serious differences with China on its northern borders and therefore stepped away from the Quad as an Asian NATO? Or has the United States itself downgraded the Quad now that Australia has joined its geostrategic game of containing China?

Before the Quad meeting in Washington, the United States and the UK signed an agreement with Australia to supply eight nuclear submarines—the AUKUS agreement. Earlier, the United States had transferred nuclear submarine technology to the UK, and it may have some subcontracting role here. Nuclear submarines, unlike diesel-powered submarines, are not meant for defensive purposes. They are for force projection far away from home. Their ability to travel large distances and remain submerged for long periods makes them effective strike weapons against other countries.

The AUKUS agreement means that Australia is canceling its earlier French contract to supply 12 diesel-powered submarines. The French are livid that they, one of NATO’s lynchpins, have been treated this way with no consultation by the United States or Australia on the cancellation. The U.S. administration has followed it up with “discreet disclosures” to the media and U.S. think tanks that the agreement to supply nuclear submarines also includes Australia providing naval and air bases to the United States. In other words, Australia is joining the United States and the UK in a military alliance in the “Indo-Pacific.”

Earlier, President Macron had been fully on board with the U.S. policy of containing China and participated in Freedom of Navigation exercises in the South China Sea. France had even offered its Pacific Island colonies—and yes, France still has colonies—and its navy for the U.S. project of containing China in the Indo-Pacific. France has two sets of island chains in the Pacific Ocean that the United Nations terms as non-self-governing territories—read colonies—giving France a vast exclusive economic zone, larger even than that of the United States. The United States considers these islands less strategically valuable than Australia, which explains its willingness to face France’s anger. In the U.S. worldview, NATO and the Quad are both being downgraded for a new military strategy of a naval thrust against China.

Australia has very little manufacturing capacity. If the eight nuclear submarines are to be manufactured partially in Australia, the infrastructure required for manufacturing nuclear submarines and producing/handling of highly enriched uranium that the U.S. submarines use will probably require a minimum time of 20 years. That is the reason behind the talk of U.S. naval and air bases in Australia, with the United States providing the nuclear submarines and fighter-bomber aircraft either on lease, or simply locating them in Australia.

I have previously argued that the term Indo-Pacific may make sense to the United States, the UK or even Australia, which are essentially maritime nations. The optics of three maritime powers, two of which are settler-colonial, while the other, the erstwhile largest colonial power, talking about a rule-based international order do not appeal to most of the world. Oceans are important to maritime powers, who have used naval dominance to create colonies. This was the basis of the dominance of British, French and later U.S. imperial powers. That is why they all have large aircraft carriers: they are naval powers who believe that the gunboat diplomacy through which they built their empires still works. The United States has 700-800 military bases spread worldwide; Russia has about 10; and China has only one base in Djibouti, Africa.

Behind the rhetoric about the Indo-Pacific and open seas is the U.S. play in Southeast Asia. Here, the talk of the Indo-Pacific has little resonance for most people. Its main interest is in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which was spearheaded by the ASEAN countries. Even with the United States and India walking out of the RCEP negotiations, the 15-member trading bloc is the largest trading bloc in the world, with nearly 30 percent of the world’s GDP and population. Two of the Quad partners—Japan and Australia—are in the RCEP.

The U.S. strategic vision is to project its maritime power against China and contest for control over even Chinese waters and economic zones. This is the 2018 U.S. Pacific strategy doctrine that it has itself put forward, which it de-classified recently. The doctrine states that the U.S. naval strategy is to deny China sustained air and sea dominance even inside the first island chain and dominate all domains outside the first island chain. For those interested in how the U.S. views the Quad and India’s role in it, this document is a good education.

The United States wants to use the disputes that Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia have with China over the boundaries of their respective exclusive economic zones. While some of them may look to the United States for support against China, none of these Southeast Asian countries supports the U.S. interpretation of the Freedom of Navigation, under which it carries out its Freedom of Navigation Operations, or FONOPS. As India found to its cost in Lakshadweep, the U.S. definition of the freedom of navigation does not square with India’s either. For all its talk about rule-based world order, the United States has not signed the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) either. So when India and other partners of the United States sign on to Freedom of Navigation statements of the United States, they are signing on to the U.S. understanding of the freedom of navigation, which is at variance with theirs.

The 1973 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty created two classes of countries, ones who would be allowed to a set of technologies that could lead to bomb-grade uranium or plutonium, and others who would be denied these technologies. There was, however, a submarine loophole in the NPT and its complementary IAEA Safeguards for the peaceful use of atomic energy. Under the NPT, non-nuclear-weapon-state parties must place all nuclear materials under International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards, except nuclear materials for nonexplosive military purposes. No country until now has utilized this submarine loophole to withdraw weapon-grade uranium from safeguards. If this exception is utilized by Australia, how will the United States continue to argue against Iran’s right to enrich uranium, say for nuclear submarines, which is within its right to develop under the NPT?

India was never a signatory to the NPT, and therefore is a different case than that of Australia. If Australia, a signatory, is allowed to use the submarine loophole, what prevents other countries from doing so as well?

Australia did not have to travel this route if it wanted nuclear submarines. The French submarines that they were buying were originally nuclear submarines but using low-enriched uranium. It is retrofitting diesel engines that has created delays in their supplies to Australia. It appears that under the current Australian leadership of Prime Minister Scott Morrison, Australia wants to flex its muscles in the neighborhood, therefore tying up with Big Brother, the United States.

For the United States, if Southeast Asia is the terrain of struggle against China, Australia is a very useful springboard. It also substantiates what has been apparent for some time now—that the Indo-Pacific is only cover for a geostrategic competition between the United States and China over Southeast Asia. And unfortunately for the United States, East Asia and Southeast Asia have reciprocal economic interests that bring them closer to each other. And Australia, with its brutal settler-colonial past of genocide and neocolonial interventions in Southeast Asia, is not seen as a natural partner by countries there.

India under Prime Minister Narendra Modi seems to have lost the plot completely. Does it want strategic autonomy, as was its policy post-independence? Or does it want to tie itself to a waning imperial power, the United States? The first gave it respect well beyond its economic or military clout. The current path seems more and more a path toward losing its stature as an independent player.

Prabir Purkayastha is the founding editor of Newsclick.in, a digital media platform. He is an activist for science and the free software movement.

China and Nicaragua: ‘Two Revolutions Working Together’

Nicaragua leapt forward to defend its national self-determination against U.S. global hegemony when it announced earlier this month it had discontinued diplomatic relations with Taiwan and was ready to join China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

“Nicaragua declares that it recognizes that there is only one single China in the world,” said Nicaraguan Foreign Minister Denis Moncada at the Third Forum between the Communist Party of China and Political Parties of Latin America and the Caribbean. There, the political parties leading the Chinese and Nicaraguan governments—both in the crosshairs of U.S. economic, diplomatic and military aggression—agreed to develop friendly relations.

This move opens up the small Central American country’s economy to the People’s Republic of China, a country of 1.4 billion people that is rapidly edging toward surpassing the United States and becoming the biggest economy in the world.

Taiwan: Washington’s Beachhead In China

Nicaragua’s move to recognize China is no different than what the United States, Japan and Canada voted in favor of in 1971 at the United Nations General Assembly. Resolution 2758 stipulated the United Nations “expel forthwith the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek” (the leader of the Chinese nationalists, whom the communists struggled against) and change China’s name as a member of the UN Security Council from the “Republic of China” to the “People’s Republic of China.”

Nicaragua first established relations with Taiwan in the 1990s, after U.S.-backed President Violeta Chamorro took power in 1989 in a surprise defeat for the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN). Taiwan is an island off the Chinese coast that Chinese right-wingers fled to upon the 1949 communist victory.

The United States replied to the move using the language of humanitarian interventionism it has deployed to exploit and destroy countries around the world.

“The Ortega-Murillo regime continues to make self-serving decisions at the expense of the Nicaraguan people, who stand to suffer from the loss of a reliable, democratic partner in Taiwan,” tweeted Brian A. Nichols, assistant secretary for Western Hemisphere affairs at the U.S. State Department. “We encourage the int’l community to continue strengthening its relationships with Taiwan.”

The Ortega-Murillo regime continues to make self-serving decisions at the expense of the Nicaraguan people, who stand to suffer from the loss of a reliable, democratic partner in Taiwan. We encourage the int’l community to continue strengthening its relationships with Taiwan.

— Brian A. Nichols (@WHAAsstSecty) December 10, 2021

Relations between the Biden administration and the Ortega government have recently taken a plunge. First, the United States intervened in Nicaragua’s elections by calling them a “sham” prior to Election Day and despite the presence of “232 international election observers,” said Michael Campbell, Minister Advisor for Foreign Affairs. After the FSLN won the election with 75.92 percent of the votes, U.S. President Joe Biden signed the “Reinforcing Nicaragua’s Adherence to Conditions for Electoral Reform Act of 2021,” also known as the RENACER Act. This law calls for the United States to monitor Nicaragua’s relationship with Russia as well as U.S. sanctions that would disrupt multilateral financing from institutions like the World Bank. Later, the Biden administration banned all Nicaraguan government officials, along with their spouses and children, from entering the United States.

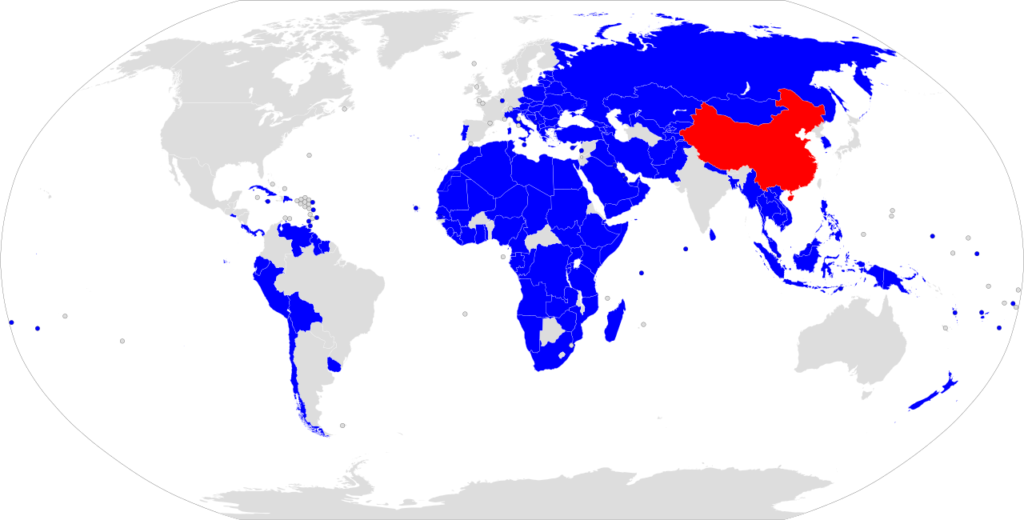

Nicaragua is now the fourth country in the region to recognize China. Panama took the step in 2017, then came El Salvador and the Dominican Republic in 2018, and Honduras, which may make the same move after left-wing presidential candidate Xiomara Castro’s recent victory.

Recognizing one China comes on the heels of the Nicaraguan government’s decision to withdraw from the Organization of American States (OAS) on November 19.

“We have seen what the U.S. and the European Union are capable of doing and have to prepare accordingly,” Campbell said. “But it’s the FSLN government’s job to lead the Nicaraguan people toward development.”

Nicaragua and the Belt and Road Initiative

The third China-CELAC Forum involved approximately 117 political parties and organizations from 30 Latin American and Caribbean countries. CELAC stands for Community of Caribbean and Latin American States. At the forum, they proposed strengthening their relationship and solidarity with China.

“Nicaragua actively supports and is ready to consult on Belt and Road cooperation documents, with a view to signing them as soon as possible,” Moncada said. In 2020, trade agreements between Taiwan and Nicaragua reached $168 million, while trade with China accounted for less than $50 million. A potential trade ceiling exists with the much-smaller Taiwan, with its population of 23 million.

In addition, the new initiative opens up markets for Nicaragua’s agricultural business.

“There is a lot of enthusiasm because communication channels have already opened up for the structuring of cooperation projects, commercial exchange and investment projects,” said Fausto Torrez. He leads international relations for the Rural Workers’ Association (Asociación de Trabajadores del Campo [ATC]).

The FSLN government has a record of working to ensure the rights of farmers, as well as of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples in the autonomous regions on the Caribbean coast. That includes bringing electricity and paved roads to these once-underdeveloped areas. The Red Nacional Vial, a 24,763-kilometer (15,387-mile) paved road, connects the Pacific Ocean coast with the Caribbean Sea coast. It has been touted as the key to connecting Nicaraguan farmers with international markets. The World Bank also praised the project for uplifting Afro-descendant people. “This region, before the road construction, could only be reached by air during most of the year owing to heavy rains and impassable infrastructure (the rainy season lasts nine months in that region),” a 2020 World Bank report stated.

Nicaragua belongs to the Central American Common Market (CACM), which includes Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. The United States is CACM’s largest trade partner, while China is the second-largest.

“These agreements come in the framework of [defending] food sovereignty,” Torrez said. “Therefore, China arrives with many possibilities to improve the country’s situation.”

As some see it, China is repairing holes U.S. imperialism has left in the region.

“Latin Americans know only too well what imperialism looks like, in both its colonial and modern forms,” activist Carlos Martinez recently wrote. “They have witnessed CIA-sponsored coups from Guatemala to Chile, from Brazil to the Dominican Republic.”

The new wave of governments working with China are doing so based on mutual respect. In 2020, $315 billion in agreements between Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and China had been recorded.

“With projects such as the sea port on the Caribbean, improvements to our airports, roads, irrigation system and energy infrastructure, we will produce more and more efficiently,” Campbell said.

Nicaragua receives the first 200,000 doses of a donation of 1 million doses of Sinopharm vaccines. The batch arrived from China with a Nicaraguan delegation headed by @LaureanoOrtegaM, Minister of Finance Ivan Acosta, and Chinese Foreign Affairs Representative Yu Bo. pic.twitter.com/QF3thXADW5

— Kawsachun News (@KawsachunNews) December 12, 2021

China also has been at the forefront of providing the Global South with aid since the start of the pandemic. For example, between mid-February 2020 and June 2020, China donated $128 million worth of ventilators, test kits, masks, protective suits and many more life-saving items to Latin America and the Caribbean.

“This strengthens Nicaragua’s international relations in all fields,” Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega said in his first public statement after the FSLN signed the agreement with the Communist Party of China (CPC). For example, the country’s National Human Development Plan will continue to prioritize poor and vulnerable sections of society, which includes rural producers. Campbell said this new relationship represents an opportunity to diversify exports in a large new market.

Two Revolutions

Ortega made clear the historic significance of acknowledging one China.

“It hurts (the United States) more when it comes to Nicaragua, which is a revolution meeting again with another revolution,” he said.

Both the FSLN and the CPC are products of national liberation movements against a colonial power. They agreed to develop friendly relations based on “mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality, mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence,” stated the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Ortega also pointed out the hypocrisy of the United States demonizing countries that establish diplomatic relations with China while the United States continues to trade with China.

Yet, sanctioned and blockaded countries that establish ties with China weaken the U.S. stranglehold.

“Now is the time to improve and strengthen A.L.B.A.,” Torrez said of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America, a political, economic and social alliance in defense of independence and self-determination in the Americas.

Abraham Marquez is a freelance journalist from Inglewood, California. He is a member of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ) and a 2021 University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism Fellow.