More than 10.3 million acres of primary tropical forests—spanning about the size of Belgium—went up in flames in 2020. A new coalition claims it will mobilize $1 billion to thwart global climate change’s increasingly devastating forest fires. But scientists and other experts have raised doubts about this new program corporations and governments have kicked off.

Primary tropical forests are untouched by human development. More than 1 billion people live in and depend on the world’s tropical forests, and nearly 300 million people live in lands targeted for tropical forest restoration, according to Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI), a non-governmental organization. Meanwhile, RRI’s data shows over 900 million people live in the biodiverse areas of low- and middle-income countries.

The new coalition is called “Lowering Emissions by Accelerating Forest finance”—or LEAF—and it is expected to become “the single largest private-sector investment to protect tropical forests.” At the Leaders Summit on Climate on April 22, multinational corporations entered into a coalition with the governments of the United States, the United Kingdom and Norway. The list of corporations includes Airbnb, Amazon, Bayer, Boston Consulting Group, GlaxoSmithKline, McKinsey & Company, Nestle, Salesforce and Unilever.

Experts have raised this coalitional strategy could further marginalize communities dwelling in tropical forests across the developing world. They also have questioned the effectiveness of strategies that aim to raise funding to halt deforestation.

For example, Forrest Fleischman, an assistant professor of forest resources at the University of Minnesota, says the success of the LEAF coalition will depend “not on their ability to mobilize money from wealthy companies, but in their ability to negotiate complicated political arrangements which may involve challenging the powers that be, including states and private companies.

How Has Carbon Finance Worked?

Political and economic conditions create opportunities for power plays in carbon finance, i.e. the funding provided for carbon sequestration programs like forest restoration. In most cases, governments, corporations and aid organizations have immense discretionary power regarding carbon finance. That is why experts say Indigenous and other forest-dependent peoples should have primary decision-making power over monetary allocations, as well as the power to choose projects.

Not involving such communities can erode their rights. For example, consider how afforestation programs in India have been carried out on lands used for agricultural purposes by Indigenous and forest-dwelling communities.

Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, former United Nations special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples, says forest conservation programs like LEAF “cannot work if the rights of Indigenous communities are not protected and the flow of money only leads to violence and conflicts” because of struggles over land rights. More specifically, she highlights a need to ensure land rights of forest-dwelling communities are recognized and that these communities play an active role in designing the LEAF program, as well as receive a fair share of the resources LEAF aims to gather.

Indigenous communities, such as the Yurok tribe in what is known as northern California, the Suquamish tribe in what is known as the Seattle, Washington area, as well as the U.S.-based Indigenous Environmental Network, could not be reached for comment, as of press time.

Fleischman also emphasizes LEAF’s aim ought to be to “transform the economic and political conditions surrounding forests, rather than just setting up conservation areas and providing payments to people.”

As for effectiveness, past efforts offer lessons.

“In Brazil, deforestation is a major source of emissions. So, it is important to have [internationally mobilized] resources to fight the climate crisis. But, at the same time, we worry when we hear about new funds to support forests because we have seen how the Amazon Fund has been used,” says Maureen Santos, policy officer at Federation of Organizations for Social and Educational Assistance in Rio de Janeiro.

Santos adds President Jair Bolsonaro’s government has failed to use the fund as a climate change tool. Deforestation rates in the Amazon have surged under Bolsonaro.

The Amazon Fund is a REDD+ initiative the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) recognizes. “REDD” stands for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation. The aim here is to provide economic incentives for forest conservation. But reports have pointed to high deforestation rates in the Amazon basin, even after the Amazon Fund was fully operationalized.

Pays to note a leading partner at LEAF is the United States, which is the biggest historical emitter of CO2. “Initiatives like LEAF have to be followed up with stronger initiatives to reduce emissions, because even if you save all the forests in the world, you cannot solve the climate crisis until you stop emissions,” Santos adds.

Recognizing Land Rights and Asymmetrical Power

A recent paper that analyzed what happened with the Yurok tribe, who occupy the redwood forest of northern California in the United States. The tribe obtained funding to enable carbon sequestration on ancestral territory. This is different than what is known as the “Indian model,” which includes large-scale plantation drives by the government under the Paris Agreement and other forest conservation, afforestation and reforestation efforts funded by international agencies like the World Bank.

The paper highlights when land managers and users possess enforceable rights, like in the case of the Yurok tribe, “power is balanced, accountability is clear, authorities represent the interests of the broader user community and carbon storage aligns with local interests.”

In India, the report found, forest carbon finance is controlled by state governments who “do not share benefits of carbon finance with the rural forest-dependent people whose actions play a major role in determining the outcomes of these programs.”

Communities dependent on forests also lacked countervailing power because their rights to forest land are not recognized.

One of the key findings of the paper is mobilizing money is not enough to ensure forest protection. This is because a wide variety of influences impact forest conservation, many of which are not directly related to financial incentives. Fleischman, the lead author of the paper says, “We’ve long recognised that insecure land tenure is a major driver of forest loss, however it is not clear how giving a country or state money leads to securing land tenure for poor or marginalized people.”

Financial investment, including ones that aim to promote forest conservation, do not work out well. This occurs, Fleischman explains, in cases where financial investments in land end up undermining secure land tenure, which then leads to land degradation. When land values increase, owing to interest from international funding agencies, power actors like companies, states and NGOs are incentivized to control land-based revenue by grabbing land for themselves. This process forcibly takes away the land rights of rural and Indigenous people.

The problems that arise from not recognizing land titles extends to Brazil, too.

Santos adds the first priority ought to be to ensure community land rights are recognized, and environmental regulations and oversight mechanisms are strong enough to assess the success and failures of proposals like LEAF.

Organizations that monitor land use, such as Land Conflict Watch and Vasundhara in India, as well as Amazon Watch, could not be reached for comment.

The Path Ahead

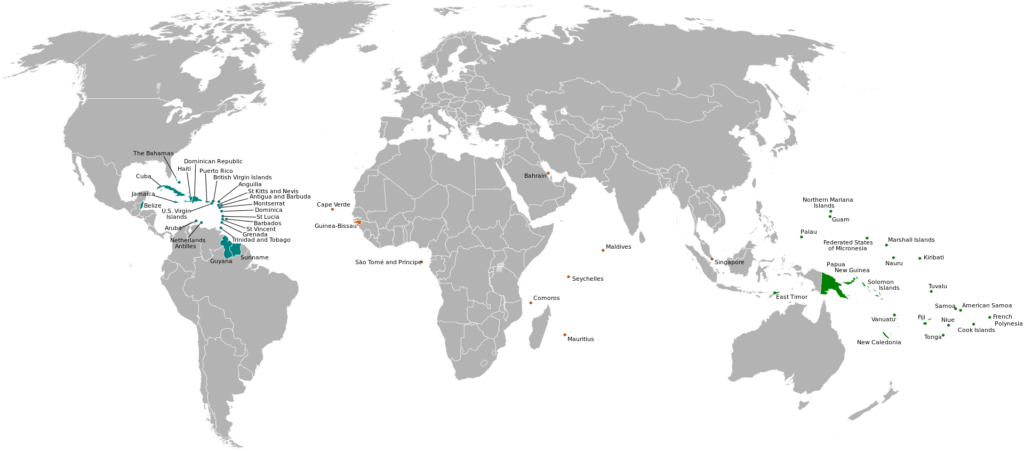

“Substantial investment in the recognition of Indigenous and community land rights is a prerequisite to the global climate agenda,” concluded a study published in June by Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI). The authors looked at 31 countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America, which hold 70 percent of the world’s tropical forests to highlight risks in developing carbon markets without first settling the land rights of Indigenous communities.

Bryson Ogden, associate director for strategic analysis & global engagement at Rights and Resources Group—the secretariat for RRI—notes “serious power imbalances” in the geographies where the LEAF Coalition plans to operate. He adds power imbalances between companies and governments on the one hand, and rural communities on the other, “often exacerbated by insecure land tenure, have driven land-grabs and violations in the past, and more recently, hindered efforts to eliminate supply chain-driven deforestation.”

In response to concerns about power asymmetries and land rights, Emergent Media, administrative coordinator of LEAF Coalition, told Toward Freedom that LEAF participants recognize Indigenous peoples and local communities are “essential stakeholders in the design and implementation” of plans to reduce deforestation and maintain forest cover in the jurisdictions where they live.

Emergent Media noted safeguards have been drawn up to ensure protection and respect of land-tenure rights and effective stakeholder participation. They also added these safeguards are based on the Cancun Safeguards drafted by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

But doubts still remain. Nothing is concrete in either publicly available documents about the coalition, nor in its statement that Indigenous and local people are directly involved in the design and evaluation of projects. Fleischman pointed out it seems like the coalition is treating Indigenous and forest-dependent people “as secondary people who need to be protected in projects designed and financed by others, as opposed to directly empowering those people to make decisions about their lands.”

The kind of economic and political changes that are needed to “ensure [forest] conservation when it conflicts with the profits of companies and the interests of national governments” are left lacking, Fleischman says.

Ogden of RRI suggests a just way to achieve emission-reduction aims would be to scale-up the legal recognition of customary land and resource rights of forest communities—including the carbon stored therein—across proposed accounting areas; develop operational feedback and grievance redress mechanisms; and adequately involve affected constituencies in the design of benefit sharing plans.

The question remains of whether the $1 billion LEAF proposes to raise is enough to conserve tropical forests around the world.

“To the extent that money can address conservation challenges, the quantity of money may need to be much larger to make a real dent. In other words, if money is what matters, the money may need to be roughly equivalent to the potential profits to be made by clearing forests to grow soybeans or palm oil,” Fleischman says.

Rishika Pardikar is a freelance journalist in Bangalore, India.