Editor’s note: We’re glad to share this reflection by Charlie H. Stern on being disabled and queer in the United States during the coronavirus and the HIV pandemics. It was written in the months prior to the ongoing uprising against anti-Black racism and the police that followed the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in May.

I called my lawyer to talk about my will. In the era of the novel coronavirus, even the young and childless are confronting death. And, we in the disabled community are seeing our fears confirmed in a new terrain of stark class inequalities, resurgence of eugenicist thought, and deprivation of essential supplies.

I’ve been thinking about my own mortality since the year two of my friends died and my health started spinning out of control.

Milo Wright, a promising young poet born with a form of palsy and a regular in his local slam poetry circuit, died first, suddenly, of a heart-related event in March 2016. Then, in June of the same year, Caroline Wall, a reporter for FierceMarkets working specifically in the healthcare marketplace and insurance sector, was found dead in her apartment in Washington D.C., heart stopped, after a lifetime of believing she had survived the defect she was born with.

Those fortunate to know both were slammed with unimaginable grief at the rapid timing. Widespread alarm over who would be “next.” Panicked check-ins with friends and family. Urgent scheduling of doctor’s appointments. My first ever MRI was the day after Caroline’s funeral.

For those of us living at the intersections of chronic physical and mental illnesses, we’ve had to face the end, and how we leave things for our survivors, early on. Not only is death looming, death is baffling and disorienting.

This year, at the beginning of the novel coronavirus crisis, a dear friend of mine, a production assistant at a major media corporation, and immunocompromised herself, made the decision to check herself into an inpatient facility. Her doctors hadn’t seen her inflammation levels this high, and isolation was beginning to take its toll, emotionally. Another friend, a long-distance comrade and peer who struggled with addiction and chronic pain, died suddenly at the beginning of April, and our shared community fears that it may have been a suicide.

With this in mind, I made two phone calls, amid not only COVID-19 panic but the terror of being alive, to my lawyer in Philadelphia, and my dear friend Carly, who manages Human Resources at a clinic in one of North Carolina’s main coronavirus hot spots.

Carly, whose workplace prefers that she keep her last name private, wrote her will when she was 19, and had it notarized officially when she was 22.

She grew up a very sickly child. In grade school, when anyone in her school building had a stomach virus, she was always guaranteed to catch it, even if she did not share a class with the person. Something was clearly wrong from the beginning. She received her first diagnosis at age seven: panic disorder.

Throughout her adolescence and young adulthood, Carly experienced a range of mystery symptoms from infections and migraines to seizures, and even a diagnosis of lupus that has since expired, downgraded back to question marks and limbo.

Early on in the COVID-19 scare, she began having suspicious symptoms on her first day of remote work, a distance she had asked her employer for, before most workplaces offered the option.

The statistics for lupus patients who have contracted COVID-19 are not good, and per President Trump’s hysteria, hydroxychloroquine, an essential lupus drug, has been bought, stockpiled, and hoarded by many Americans who do not have the diagnosis and never will.

Since Carly is back in an undiagnosed category, seeing doctors to explore new and worsening symptoms proves nearly impossible right now. The work she has dedicated her energy to is keeping her coworkers, mostly clinicians who do in-person, and often in-home visits, safe.

Citing her own lived experiences with poverty, she tells me she has had to get creative with sourcing vital supplies such as bulk hand sanitizer and reusable masks.

To call this pandemic a class war would be an understatement.

Those who are served by the clinic where Carly works are primarily low-income families for whom “telehealth” visits are prohibitive: in terms of costs of contemporary technology; need for clinicians to provide childcare as well as rehabilitative services; not to mention the general material medical services, like installation and changing of catheters, that many patients may require.

Within the chronic illness community in the United States, if it is even accurate enough to characterize a statistical grouping as a community, a majority of people are either low-income or unable to work, or are consistently bankrupted by healthcare costs, medication co-pays, and medical debt. And that has dire consequences for one’s mental well-being and sense of safety. Trauma is a multi-pronged animal.

Leaving a will

As I have no children, few assets, and consider “freelancer” a nicer self-description than “impoverished shut-in,” I asked attorney Adrian Lowe, of the AIDS Law Project Of Pennsylvania, if I should even bother writing a will.

Lowe, speaking on 31 years of experience advocating and protecting the rights of mostly (but not all) LGBTQ, mostly HIV-positive, low-income clients, was firm with the advice that a will and funeral plans are important to have prepared and documented, especially for a queer and trans person like myself.

Not only do poverty and chronic illness go hand-in-hand, oftentimes, contemporary queer history and activism contend with mortality in their own ways.

Lowe shares that he is observing somewhat of a return to what he calls the “cowboy lawyering” that was necessary during the wave of the AIDS crisis, contemporarily with COVID-19: the rushed, frantic, bedside strategizing with the dying.

Disability inherently has no fixed meaning, and is a category that anyone of any race, income level, or sexuality can be included in. However, with Millennials who may be at somewhat unprecedented crossroads of marginalized identities, poverty, and chronic physical and mental illness, this particular lawyer says it is a good idea to protect ourselves and our legacies, our chosen families, and our partners.

Before same-sex marriage was legal, the drawing up and notarizing of wills for queer couples was often celebrated with cake, flowers, and many witnesses, in law offices. This was how we protected ourselves, Lowe explained.

Otherwise, most people who initiate or complete intake for will-writing nowadays, according to Lowe, are those who have had recent brushes with death, those who have new diagnoses, and those who become parents.

With COVID-19, now notarization is as much of a public risk as any other in-person interaction. For people who are at heightened danger due to pre-existing illnesses? Lowe tells me that handwriting your own wishes in the form of a will, every single word, is legally valid and proves not only that it is fully one’s own wishes, but that the will was written completely in sound mind.

This may be crucial information. It is important to note, as well, that suicidal ideation does not nullify the “sound mind” requirement, and it could potentially be useful for folks who have lost their jobs, who are worried for their own health, or are overwhelmed by the general state of the world, to solidify one piece of full autonomy and choice.

Furthermore, it is your right as a human who lives under the coercive rule of a governing state, unreliable as it may currently be, to use the arms of that state for protection as best as you can. Or at least until it isn’t anymore.

Self-determination, in life, and after life.

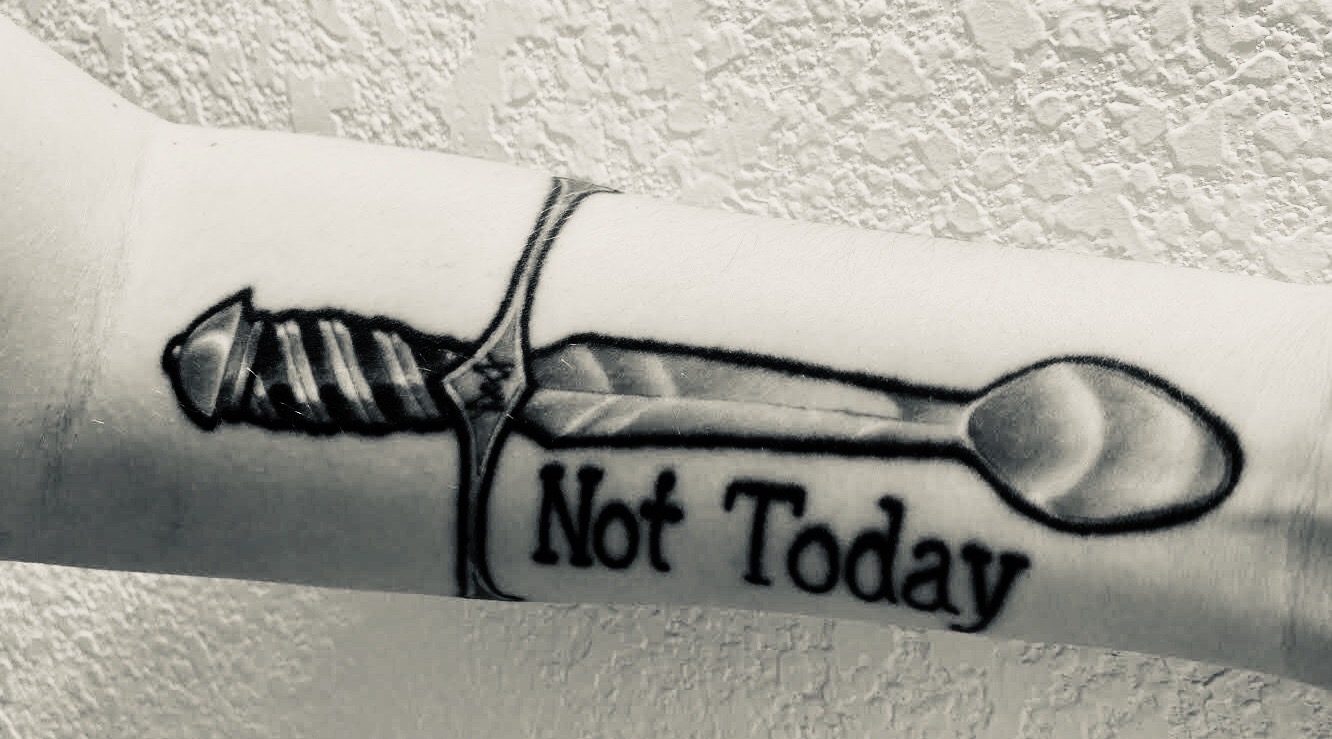

In closing, we remember the dead, and we anticipate the coming of more. We participate in whatever levels of self-preservation and community mutual aid we are capable of. We recognize the new eugenics of global coronavirus response, we sit with this fear, and we ponder the imagery of a spoon as it relates to the Spoon Theory and its symbolic power for disabled and chronically ill people everywhere. A tool, a talisman. Once tattooed on Milo Wright’s body, now tattooed on Carly’s forearm in tribute, the spoon bears the message:

“Not today.”

Author Bio

Charlie H. Stern is a deeply religious, deeply ill, Jewish anarchist; grief scholar; and pro-wrestling adjacent photographer/artist living on the East Coast. Their work can be found in Dream Pop Press, Visceral Uterus, Weasel Press (Vagabonds), Mondoweiss, and Earth First! Journal.