In the epilogue to the most recent edition of Nuestros años verde olivo, Roberto Ampuero meditates on what led him to write his memoirs about his time in Fidel Castro’s Cuba in the form of a novel. He concludes that only novels are able to fully capture the realities of human life, the depths of its moods and the texture of its circumstances, owing to the novelistic genre’s knowledge of the passions, cruelties and benevolence of the human soul.

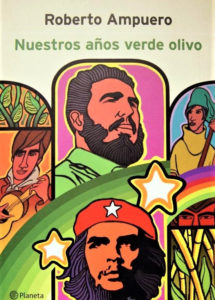

Its title, which translates as Our olive green years, alludes to the colour of the military uniform typically worn by Cuban political leaders. It is with shock that I learned that this novel has not yet been translated into English, both because of its bestseller status in its original Spanish, and because as a personal account of the political realities of Castro’s Cuba, it is irreplaceable.

This roman-à-clef (a novel relating real events, but in which the names of its characters have been changed) is the perfect companion to Jorge Edwards’ Persona non grata. Both relate the disappointment of left-leaning intellectuals upon experiencing the realities of Cuba in the 1970s. Both have been banned by the Castro brothers. Edwards’ book was published shortly after his stay on the island; its truths were therefore revealed in near-real time. In contrast, Nuestros años verde olivo first appeared in 1999. Ampuero thereby sacrificed contemporaneity but gained a half-lifetime of reflection and contextualization.

Nuestros años verde olivo commences when its author, still in his twenties, flees his native Chile in the wake of Augusto Pinochet’s 1973 coup and subsequent military regime. He goes into exile in East Germany, but soon falls in love with Margarita Cienfuegos, the daughter of Cuba’s ambassador in Moscow. At the time an enthusiastic communist and a fervent defender of the Revolution, young Ampuero travels to the Caribbean island, where he marries and settles.

Over the course of the book’s 600 pages –which, as gripping and superbly paced as they are, one reads in as few sittings as one’s other commitments allow– young Ampuero’s enthusiasm for Castro’s regime progressively dwindles. One of the effects achieved by the novelistic form is that this disenchantment is not explained in the abstract through Ampuero’s retrospective narrative voice; rather, it emerges gradually from the readers’ first-hand encounters with the author’s concrete experiences. It is therefore felt as one’s own.

The first of these disappointments is the irony of discovering that the diplomatic family into which the author marries enjoys privileges –a mansion previously owned by Fulgencio Batista’s aristocracy; access to food, clothes and jobs not available to the average Cuban citizen– that run against the grain of the ideals that they profess and enforce.

Over the course of the novel, these jarring contradictions grow in severity. There are the hundreds of extra-judicial murders commissioned by Castro, as well as by Ampuero’s father-in-law. There is the systematic ostracism of Ampuero’s friend, who is found guilty of storing counter-revolutionary books, as well as the disappearance of many other friends and companions who enlist to fight in Angola and Nicaragua.

There are also Ampuero’s own politically determined personal tragedies, including being denied permission to visit his ageing parents, who lived overseas, and eventual bankruptcy and homelessness. The world in which young Ampuero and the reader end up bears cold and uncomfortable similarities with Pinochet’s Chile, the very country that the author initially fled.

Emboldened by adversity and disillusion, Ampuero eventually finds the courage to speak honestly with one of his comrades from the Cuban branch of Chile’s Communist youths. The long list of individual tragedies that Ampuero exposes are rebutted and justified with statistics, namely fast-growing literacy rates and plummeting infant mortality rates brought about by the Revolution’s generosity.

The net amount of Cuban suffering, our comrade informs us, has fallen owing to Castro’s policies. Ampuero’s reply captures one of the book’s fundamental premises: “Pain is not multiplicative.” In other words, the categorical wrongs of curtailing individual life and freedoms cannot be made right by appeals to national achievements.

Readers may disagree with Ampuero’s conclusion and think that the successes of the Cuban Revolution do justify the political and personal repression that have accompanied them. After all, the question of whether it is morally permissible to harm the few in order to benefit the many is an age-old philosophical conundrum.

Readers should not expect Nuestros años verde olivo to provide a definitive answer to whether the Cuban Revolution was a success or a failure. This question is far too complex, both at philosophical and political levels, for its answer to lie in a single book. In fact, even if all the relevant arguments were laid before us, we would ultimately have to decide for ourselves whether we lean one way or the other.

Ampuero’s contribution to this debate is a deeply relatable account of what was lost along the Revolutionary road. A single testimony may not sound like much when trying to understand the realities of a whole nation, but this novel makes a strong case that the opposite is true: there are things that cannot be apprehended through abstractions, generalizations and statistics.

The words of Spanish writer and literary critic Antonio Muñoz Molina are relevant here. In a recent essay, he suggests that the great universal lesson of the novelistic genre is that individual life exists over and beyond all doctrines. In its deep, personal sincerity and in its wholehearted commitment to the individual and the specific, Nuestros años verde olivo honours that lesson.

The lessons that readers derive from Nuestros años verde olivo are as necessary today as they must have been to its protagonist in 1970s Cuba. Bernie Sanders, for example, faced criticism during his run in the democratic primary for having lauded Cuban advances in public education and the USSR’s healthcare services. In Chile, memories of Allende’s politics and Pinochet’s dictatorship have surfaced over months of protest and constitutional debates.

Ampuero’s novel gives a political dimension to the Spanish idiom, una cosa no quita la otra, which translates (loosely) as both things can be true. Yes, the public healthcare and education enjoyed by most Cuban and Soviet citizens resulted in drastic improvements to their wellbeing, and yes, the crimes committed by both dictatorships are real and atrocious. We often insist on denying indisputable advances on the basis of the political and personal repression exerted by those same regimes, or on justifying and feigning blindness to the latter on the basis of the former.

Faced with such irreducible complexity, and somewhat aside from Ampuero’s political involvement in the last decade (he has taken various positions in Sebastián Piñera’s conservative administration in Chile), his book reveals with clarity that even if one decides that individual sacrifices are justified by collective successes, those losses can never be morally dismissed.

This argument cuts both ways: should readers agree with Ampuero’s conclusion on the Cuban Revolution, they would be mistaken to dismiss its social successes on the grounds of the repression it exerted. Both things can be true. Nuestros años verde olivo should be read as an invitation to navigate in the midst of paradox, and to ultimately decide for ourselves. For all these reasons, and no doubt for others, Ampuero’s novel deserves to be translated into English.

Author bio:

Rogelio Luque-Lora is a doctoral researcher in the Department of Geography of the University of Cambridge. His work focuses on the political, cultural and ethical dimensions of human-nature relationships. Find him on Twitter at @rogeluque.