At the end of December, a group of women from different organizations, among them feminists, university students and artists, all of whom are in struggle, broke our silence. “We will no longer be silent, we will no longer allow them to keep threatening to rape us and abuse our bodies,” we said as we took the streets of downtown Cochabamba.*

Holding hands, lined up, dressed in colors, wearing flowers, masks, and with unflinching conviction, we took to the streets to express our feelings. Up until now the crisis in Bolivia has only unleashed hate, uncertainty, fear, and violence in a confused polarization that attacks women first, and threatens us in various ways.

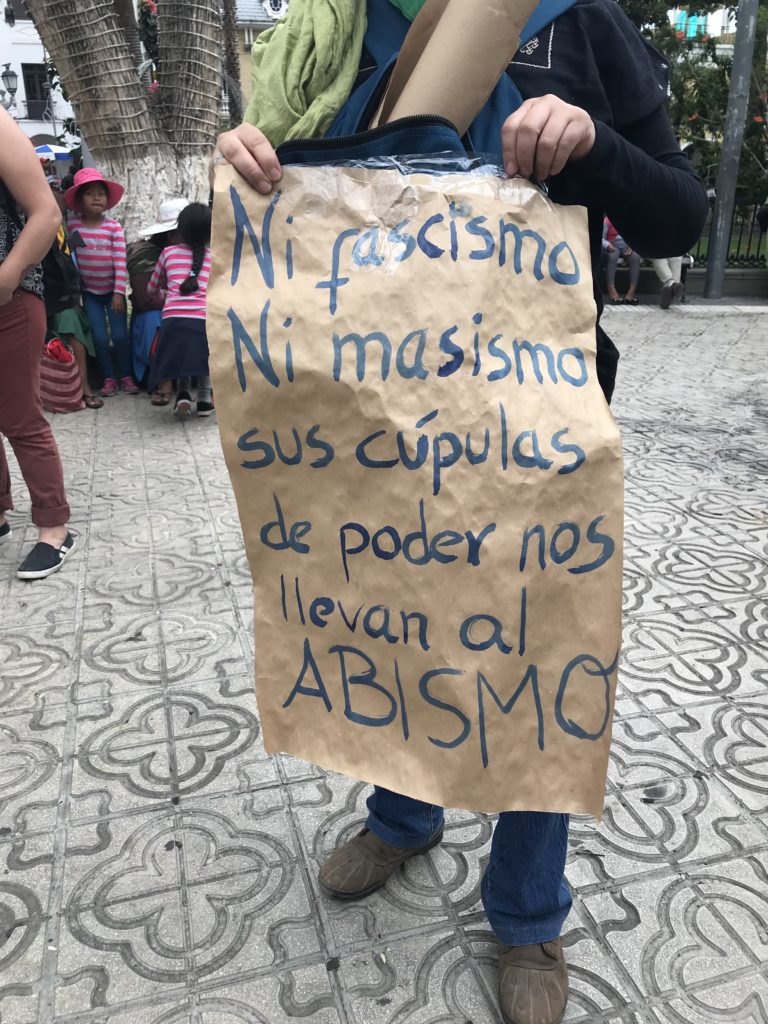

Many of us stayed silent in the public sphere for a long time. “The silence is suffocating me,” said more than one of us when we met to organize the action. On a sunny Monday afternoon, we gathered in a small plaza to put our own words on signs to express how the logic of war affects us all. For us, disarming the war means unmasking the limits of the supposed truce achieved through high level partisan negotiation. But that peace does not trickle down to our everyday reality, which continues to be clouded by violence. We called for a mobilization with a slogan that has been repeated not only in the last Women’s Parliament organized by the Wañuchun Machocracia Articulation (Death to the Machocracy), but also in several of the encounters among women: “Macho violence is leading us to the trash.”

In the crisis that has broken open in Bolivia since November, we have constantly felt subsumed by an aggressive dynamic that did not allow us to entirely digest anything because of the pace of change. However, amid so much confusion, there was also repetition: rape as a language, mandate, and practice used by both sides, telling us that the logic of war is against women, youth, and children of all ages. We therefore want to politicize rape and warn against the danger of naturalizing it.

“We women will organize organize ourselves and we will disarm this whole war!” is the cry that brought us together when we took the streets of the city center. We ended up in the Plaza 14 de Septiembre, where we hoisted a Christmas tree filled with our own words, including the word noganchis, which is an all inclusive we.

For women and feminist organizations of Llajta, as Cochabamba is called, denouncing the foundation of a violent war is not just necessary, it is urgent. “Evo did not save us, the motoqueros (members of a paramilitary group that travel on motorcycles) did not protect us, the police did not keep us safe. We take care of each other, we protect ourselves!” chanted the youngest women during the public action.

As women, we are determined to continue a dialogue together, and therefore we are working to care for and nourish the spaces in which we can exercise our own political forms. At the beginning of this year, we organized an assembly to analyze the political context, and so that we could listen to one another. We felt the need to construct our own narrative about what had happened during the crisis.

Building our own narrative has not been easy. We are conscious that the logic of polarization encompasses various sensory levels that structure our comprehension of reality. The puzzle is still not complete. In the meantime, we are determined to politically educate and activate ourselves, understanding our differences, and from them mobilize together against the expansion of colonial and patriarchal control and interference.

Continuing the thread of mobilization, on February 6 and 7, we organized two events: the first to seek redress to the women cholas who had been attacked by the self-styled Cochala Youth Resistance (RJC). We carried out an autonomous and non-partisan recognition of our lineages, in a context that tends to essentialize the use of traditional skirts, called polleras.

We entered the Cala Cala Plaza in a line, with photos of our mothers and grandmothers hanging from our necks. That afternoon, as part of the recognition of our lineage, we vindicated our women ancestors. We organized with the clarity that feminism provides, allowing us our own space of enunciation based on political autonomy. We are shaping alliances with other women and organizations based on differences and plurality. Our ways of doing politics allow us to de-essentialize identity, working through our colonial wounds by recognizing that our Indigenous roots do not make us guilty, rather, they give us freedom.

On the second day, women and men celebrated together in coordination with the compañeras of the Rebeldías Lésbicas (Lesbian Rebellions) and the Congreso de Mujeres Lesbianas y Bisexuales de Bolivia (Congress of Bisexual and Lesbian Women of Bolivia), called for a ritual of offering and amends in Cochabamba. We again took over the Cala Cala, this time to fill it with our collective energy. We k’oamos (gave offerings) to heal the space and call our ajayus (souls), while we were filled with certainty that our way of doing politics –which is threatened by liberal and partisan impositions– is vital and forceful.

Connections in Real Time

I write after having received the news of the femicide of 25 year old Ingrid Escamilla, murdered by her boyfriend, Erick Francisco Robledo, 20 years older than her, on Sunday February 9. Ingrid’s body was skinned after she was murdered in her house in the Gustavo A. Madero delegation of Mexico City. Two media outlets were denounced for publishing images of her body, in complicity with agents of the Attorney General’s Office who leaked the images.

The anger from the feminist movement was immediate, and protests exploded throughout Mexico. Statistics show that 11 women a day are killed in Mexico, and in a context of war, crimes against women are committed and naturalized in a brutal way. Since I have been living in Mexico, the cases have been increasingly cruel and the continuity is marked. One barely recovers from the last femicide when the next occurs. As a consequence, there is almost no time to process our emotions.

There are multiple connections between violence against women in Mexico and Bolivia. There were 22 femicides in Bolivia in January and February of this year, and there is still a long way to go towards the politicization of patriarchal violence. As in Mexico, the majority of the murders of women are committed in the home, and the perpetrator is most often the partner or spouse. Another similarity is how the media spectacularized the killing of women, intensifying a pedagogy of cruelty and leading to imitation.

In my family home, we ended our habit of watching the news at dinner time because, for a while now, all of the channels dedicate much of their content to sensational stories and feminicidal crimes. It is sickening to swallow pain and food at the same time. The re-victimization by governmental bodies and by institutions that are “responsible” for addressing violence is another commonality between Bolivia and Mexico. Finally, there is the impunity and non-resolution of these crimes.

I weave together what is happening in Bolivia with Mexico in order to take into account that the war in Mexico is responsible for propagating violence which primarily impacts communities and women. It is a counter-insurgent war that, in the name of fighting drug trafficking, depoliticizes violence, hides its objectives of disciplining and controlling the population as a whole. Looking at the historical construction of the narrative about the war in Mexico can help us better understand the post-electoral conflict and crisis in Bolivia, which in its current phase is composed of a pacification filled with confusion and multiple forms of violence. It is also important to pay careful attention to how patriarchal violence intensifies in a territory at war. That leads us to ask: what can a feminist lens teach us about the Bolivian scenario? How are we interpreting it?

The Violence of Polarization

During the most intense days of the conflict in Bolivia, between the months of October and November 2019, many of us had the feeling that we were trapped in an incomprehensible nightmare produced by the binary logic of polarization, as two sides disputed state power.

Those of us who have been generating critical reflections for a long time prior to the crisis felt unable to process the violences produced in a scenario marked by conflict between the progressive form of governance practiced by Evo Morales, and the liberal form of the right-wing, which had been widely accepted by diverse sectors in Cochabamba. The crisis that was already taking shape was apparent to us before October, as extractivist and authoritarian progressivism was challenged via liberal mechanisms, which ended up promoting the inclusion of ultra-conservative right-wing oligarchs.

The crisis in Bolivia revealed a scenario that was full of contradictions, in which the escalation of violence silenced the population in general, and women in particular. We woke up abruptly to an opaque context in which the patriarchal politics of both sides clouded the possibility of comprehension, especially between November 8–11, when the dispute over state power and military control was most explicit.

The different patriarchal pacts that emerged via polarization raised the profiles of caudillos, who, using conservative discourses corresponding to a logic of war, reproduced violence either to preserve or to take state power. This was especially evident in the most complicated moments of the crisis.

The political crisis at its heart was about the fall of one political regime and the entrance through the back door of the most aggressive and conservative right-wing, covering themselves with a very thin veil of legality. The logic of war war has used a discourse of “legitimacy” to justify military and police repression and the installation of urban paramilitaries who, in the current context, harass entire sectors of the population. It was thus that the circulation of hatred, fascism, and a profound process of social decomposition, as well as the continuity of the logic of revenge and revanchism of those occupying the state was established.

And in Cochabamba?

While the crisis settled in certain geographies during the post-electoral conflict in Bolivia, it took specific forms in El Alto and Cochabamba. In Llajta, as Cochabamba is called, the conflict was established in a particular way. This narrative is rooted in that geography and in dialogue with others who are also proposing to disarm the war.

Violeta stated that each woman experienced the conflict from a situated place determined by her geographic surroundings and according to “whether you live in the countryside or the city.” In Llajta there has been an intensification of the colonial mediation expressed in racism that had been activated particularly since 2007 when a civil war almost broke out between those in the countryside and the city.

Cochabamba is Bolivia’s third most important city economically, and the rural area is barely set apart from the city limits. Here, the borders between the rural and the urban are almost imperceptible, regardless of which, the separations that have been intensified with the conflict have been reproduced here too. The context of polarization has become a breeding ground for a surprising swell of racist violence and expressions of hatred against the peasant and Indigenous population.

The conflict brought the stigmatization and degradation of the chola (Indigenous Aymara and Quechua women). “Everyone has a chola grandmother who was born in Capinota, Arani, or Vacas” said the women with whom we marched in one of the actions last December. One of them carried a sign that said “We are diverse and free.”

It would seem that the residents of Cochabamba have forgotten that. Borders are appearing in the social imaginary and even between the north and the south of the city. The polarization generated between a mostly right-wing urban movement and Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) supporters constructs parallel histories or realities in which racial and economic divisions are encouraged. Since the elections on October 20, both sides have engaged in dialogue, using violence as a common language.

Cochabamba is also known for being a department in which the vote in favor of the MAS occurred in all electoral contests. The results of the last elections show almost 56 per cent voted for the MAS (a figure that has been in question since the day of the elections), primarily due to the strong vote in the rural area where the MAS’s corporatism brings together the peasant federations in the valleys and the cocalero movement. Cochabamba is known not only for its cuisine, but also for the production of coca in the area of Chapare, a region also linked to drug trafficking. During the previous MAS government that zone had become an “autonomous territory.” Today, the current government is threatening to intervene militarily to retake “control.”

If the dispute over the state has been the determining factor for both sides confronting each other in this polarization, it is important to mention that in this scenario marked by confrontation, the taking of state power determines the correlation of forces related to the imposition of the logic of war. The patriarchal pact that currently governs Bolivia has control of the army and the police –formerly controlled by the MAS– and thus has the means to produce a type of war under the pretense of combating terrorism and drug trafficking, which underpins the spread of armed paramilitary structures throughout the country. These elements are crucial to understanding the production of the materiality of war.

At this point it is worthwhile to reflect on the continuity of violence in Llajta. In 2019, 116 femicides were recorded nationwide. In Cochabamba, the cases add up to 25, among which there have only been two convictions, because the state and its institutions do not guarantee justice for victims of violence. Last year, Cochabamba had the second highest number of femicides in the country.

The viciousness and cruelty of the deaths, such as the case of Estéfany Jácome, who died from 41 stabs that her partner Salomón Méndez unleashed on her torso, marked the last feminicide of 2019, shows that in most cases the women were living in tremendously violent environments. This opens a reflection on how the conditions for the naturalization of violence preceded the political crisis and how the conflictive context enables the battlefield where it is legitimized.

Violence is imposing an alarming new toll on women’s bodies. We see this in recent femicides, in the impotence and rage against the murders of women, and because with the MAS or without the MAS, men keep killing us. So far in 2020, there have been five reported cases of femicides in Cochabamba, the highest number country wide after the department of Santa Cruz. The current government has declared a national alert. But while women continue to be treated as a “sector,” sexist violence is not resolved, even less so in a pre-election scenario that is shot through with patriarchal politics. In this context, racist violence and threats of rape that are committed in this context are not addressed and made invisible.

Women live violence as an everyday experience, which makes us politicize and identify it in a concrete way. While there is a “truce” in Cochabamba for now, we are living alongside threats like: “We are going to rape you with this stick” or “We are waiting to take you to that motel,” or “Fucking tomboy, we are going to stick a tube up your ass so you know what it feels like.” These are the phrases that the violent and furious men of the RJC paramilitary structure shouted at young women at a vigil during the election of Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) spokespeople at the Cochabamba Departmental Assembly in December.

These threats are nothing new. The threat of rape seems to be a directive assumed by men once they have decided to go to war. “We are going to rape you” has been their catch phrase. MAS supporters threatened to rape Soledad Chapetón, Mayor of El Alto, 200 times on November 19, 2019 when they attacked city property, in a moment of the most intense polarization.

In such a scenario, it is not surprising that the racist practices of those same paramilitaries have targeted pollera women: on January 17, the RJC violently evicted women from Plaza Cala Cala, a public space which has become a bastion for the irregular armed group. The operational legitimacy of the armed groups and the violent structures inherited from the conflict are continuously being installed to guarantee a sense of militarized security, which also intensifies the stigmatization of difference, and privatizes the use of spaces controlled by one side or the other.

It is clear that women, in and from our bodies, feel and know that patriarchal society is violent and abusive and that, no matter who governs, it legitimizes a type of state that protects people and institutions through practices of complicity, seeking to silence and discipline us. We also feel that the escalation of violence in Llajta is taking on other forms and practices that were not perceptible before the conflict, or at least weren’t as visible or legitimate. Today racism and sexism are openly and blatantly expressed. This happens in times of war: it appears that anything goes.

What unites us and why do we mobilize?

Peace has not arrived to Cochabamba, not while threats and rape continue and the continuum of violence against all women is naturalized. We are witnessing the extension of the conflict and the material establishment of a war that we are still trying to comprehend. For that reason, we defend the claim that it is necessary to politicize the current conflict and understand the logic of the groups and structures that continue reproducing violence in the name of security and protection.

These groups operate under the guarantee of people and institutions that seek to extend the times of crisis and fuel polarization, which continues producing victims. The events that reality has thrown at us are unprecedented and worrisome, and therefore they require that we pay close attention. We have also shown that a male figure is being naturalized: he is violent, armed, and has total impunity, and in the name of the binaries of war, attacks and threatens women of all ages. We have understood that this conflict seeks to entrench machos, machas, and caudillos.

In a meeting organized to share reflections, Amapola, a young mother of three children, said that she is determined to raise her voice in a time that, while complex, calls on us to gather as women, not only to denounce violence, but also to transmit to our daughters and children the struggles that we have been waging to conserve our relationships, which are under threat. We understand that disarming the war also means taking care of ourselves, taking care of our community, our elders and children, who are at risk today and growing up in a society that appears to be moving ever closer to decomposition.

We affirm that our struggle is to avoid the further destruction of our relations, which are threatened by the ongoing process of fascistization and by the violence that continues to expand daily with impunity. As women, we propose generating justice based on our own practices, and we call attention to sexual violence, which much of society wants to make invisible, naturalize, and hide.

Expressing ourselves has meant defining the interpretive principles that we will employ as we politicize the question of how to disarm this war. Our first action to politicize our fears and turn them into ideas has been to mobilize. We do so in order to transform our ideas into a practice that helps shift us away from impotence, which produced by a logic that locates women’s bodies as a target. We are opening a horizon that contains our words, our fears, our creativity, and our hopes.

We closed our action in Cochabamba by marching. Our hearts leaped to the beat of lesbian-feminist drumming. Diverse women flooded the streets of downtown Cochabamba, together in the rain, continuing to the main plaza. At the doors of the cathedral, our sisters in red burst in, saying: “We are together in the struggle, resisting everything that comes against us, that tries to crush us, today we have fury in our souls, our hearts are hurting, but our spirits are strong.” We refuse to remain silent.

*Names have been changed and quotes anonymized to protect the women who participated.

Translated by Toward Freedom. Click here to read the Spanish version of this essay.

Author Bio:

Claudia López Pardo is a Bolivian feminist and researcher who has lived between Mexico and Bolivia since 2016. This text contains the contributions from the work of common reflection with the Disarming War collective, made up of women from Mexico and Bolivia, as well as dialogues with women and activist and research collectives from Cochabamba and La Paz.