This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Activism and protests marked West Papua’s 50th anniversary last year of the so-called Act of Free Choice, which formalized Indonesia’s control over the territory, with the region’s people once again demanding independence from Indonesia.

In January 2019, West Papuan activists delivered a petition to the United Nation (UN) demanding a referendum on West Papuan independence.

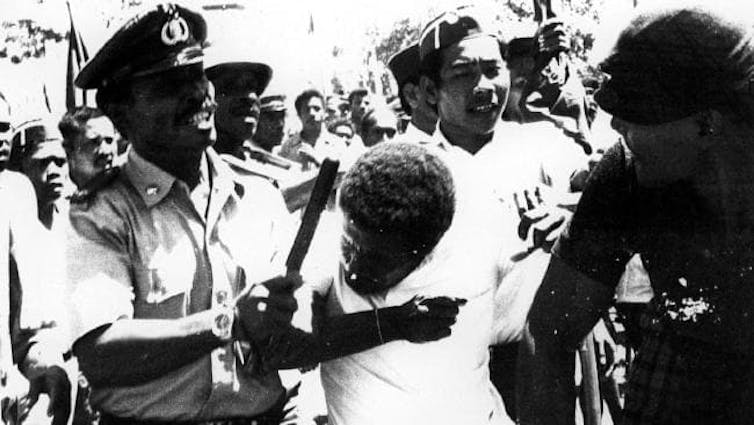

Six months later, protests broke out after Indonesian police arrested 43 West Papuan students in Surabaya, East Java. Footage of the arrests showed Indonesian soldiers racially abusing the indigenous Papuan students.

Protesters took to the streets in the months following the incident, demanding an end to racial discrimination against West Papuans within the Indonesian state and calling for a referendum on independence for the territory.

These recent protests build upon a long history of Papuan activism in response to Indonesian government repression, racism and denial of West Papuan desires for independence.

As early as the 1960s, West Papuan nationalists argued for their right to independence – under the UN’s 1960 Declaration on Decolonization – following the renouncement of Dutch control over Indonesia. However, they ultimately failed.

My recently published paper argues this failure was in part due to international political dynamics, which sabotaged West Papuans’ attempts to ride the waves of decolonization efforts by Asian and African countries throughout the 1940s to the 1960s.

Why West Papua failed in international forums

In the 1960s, West Papuan activists attempted to link their decolonization campaign to earlier struggles for independence across Asia and Africa. Triggered by instability during the post-war era, colonial countries in Asia and Africa formed connections to end colonialism.

At the UN, West Papuan activists sought the support of African delegates who they believed were likely allies. They argued West Papua and Africa shared a history of racial oppression and a desire to see the end of colonialism in all its forms.

While African leaders were sympathetic to the cause of West Papuan activists, they were already committed to the Non-Aligned Movement led by Indonesia.

This bloc supported Afro-Asian solidarity and committed leaders not to interfere in the affairs of other nations. It protected them from intervention by their former European colonial powers and from the raging Cold War politics, as they didn’t take side between the US and the Soviet Union.

Contrary to the name, the Non-Aligned Movement didn’t advocate keeping out of the Cold War, but aimed to use its alliance of Afro-Asian nations to exploit Cold War tensions for Third World aims.

Indonesia, for example, made deals with the United States promising access to mine gold and copper in Papua. Indonesia turned down Soviet aid, while also using the Afro-Asian bloc at the UN to gain support for its control of West Papua.

The Cold War improved opportunities for nations already committed to power blocs. But for the West Papuans, newcomers to international politics, it was another barrier to entry into the international community.

Afro-Asian connections had begun to solidify in the 1950s and Indonesia’s prominence within the alliance prohibited Papuan involvement.

By the time Papuan activists entered the political arena in the 1960s, Indonesia had already developed its Cold War strategy.

Alone, isolated and continuously repressed

West Papuans were denied independence also because the UN system failed to heed their calls and instead placed appeasing Indonesia above its commitment to decolonization and human rights.

After an interim period of UN administration, the Netherlands and Indonesia signed an agreement to transfer control of West Papua to Indonesia in 1962. The agreement included a provision requiring Indonesia to consult the population of West Papua on whether or not they wanted to remain part of the republic.

After intense campaigning by West Papuans, Indonesia finally announced it would conduct this act of self-determination in 1969. Yet when the referendum came, Papuans were once again denied a voice in the future of the territory.

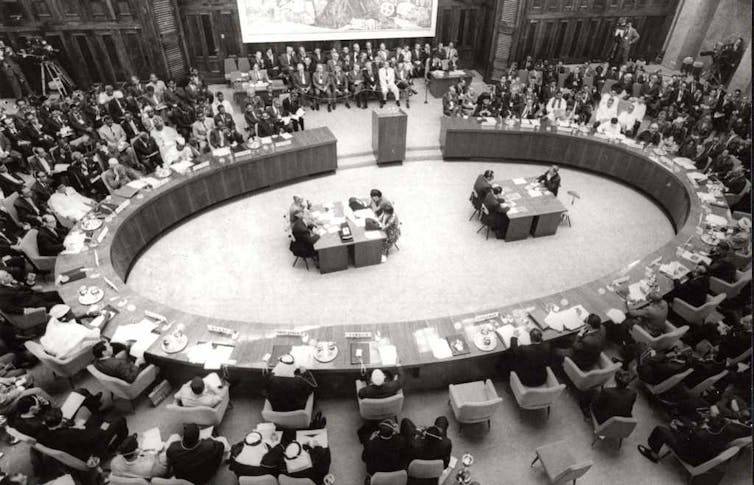

As the UN was excluded from most of the process, Indonesia went unchallenged in allowing just over 1,000 hand-picked individuals to vote on behalf of the entire West Papuan population. Under this rigged system, the men unsurprisingly voted in favour of becoming part of Indonesia.

At the UN General Assembly meeting to ratify the Act of Free Choice, many African representatives were unwilling to back it without debate as they believed it undermined the UN’s principles of decolonization.

They highlighted the hypocrisy of establishing the Non-Aligned Movement with the explicit aim of opposing colonialism and then allowing Indonesia to set up colonial-style rule in West Papua.

Despite this debate, no delegate was willing to vote against Indonesia.

The assembly voted to accept the Act of Free Choice as it was – in a vote of 84 to 0 with 30 abstentions – noting that it fulfilled the requirements and UN responsibilities of the agreement.

While the West Papuans had convinced African leaders of their desire for self-government and the unjust nature of Indonesia’s control, the African representatives were unwilling to openly vote against Indonesia and break their alliance in the Afro-Asian bloc.

To stand against Indonesia would endanger their political standing and protection in the international community. Delegates instead chose to abstain.

Will West Papua have another chance?

Several factors have changed in the international community since the 1960s.

The changes include an increase in membership of leaders from the Pacific and the recognition of rights for indigenous peoples.

Yet the preference of UN delegates to value state sovereignty over justice and equality remains the same.

Whether the activists can gain support for a referendum will depend upon their abilities to turn the tide of politics at the UN.

Current West Papuan activists have gained support from Pacific leaders and had success with officials from the UK.

However, they still need to win significant support from African and Asian delegates to tip the power balance in their favour.

As in 1969, world leaders would do well to listen to the voices of Papuan activists as choosing to ignore their calls will have dire consequences for West Papuans in Indonesia. In the words of the International Labour Organization, “If you desire peace, cultivate justice.”![]()

Author Bio:

Emma Kluge is a PhD Candidate in the Department of History at the University of Sydney.