Exploring the vastness of Gobi Desert in the 13th century, Marco Polo proclaimed it to be filled with “extraordinary illusions.” Today, Oyu Tolgoi, one of the world’s largest copper-gold mines, rises among Mongolia’s traditional herding lands, shimmering like an illusion across the steppe’s treeless, grassless plains.

Mineral-rich Mongolia, labelled “the next Qatar” by The Economist, is experiencing an unparalleled mining boom. But as mega-mines like Oyu Tolgoi ramp up production, they are creating distrust and conflict with herder communities.

The rapid rise in mineral extraction now raises the question, “Can herding survive mining?”

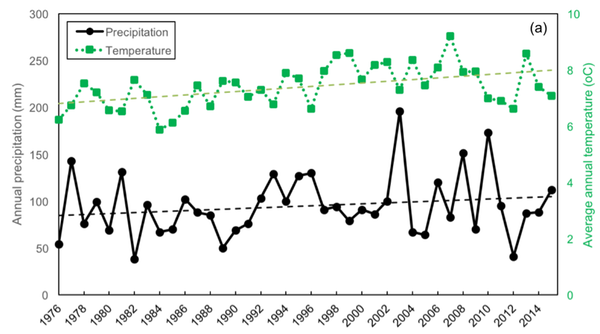

The Gobi, Mongolia’s high-latitude desert, is a harsh environment traditionally inhabited by mobile pastoralists. The dramatic steppe and its extreme aridity form an important backdrop to herding activities, with low rainfall, droughts and extreme dzud winters.

The unpredictable climate make seasonal animal migrations (known as otor) exceptionally challenging here. For six millennia, Mongolian herders adapted to water and pasture scarcity with Traditional Ecological Knowledge. But Soviet collectivization centralized and controlled their herding practices, making them less mobile and less resilient to environmental shocks.

Today, these adaptive strategies are being further threatened by resource extraction. Mines can have negative environmental and socioeconomic impacts on herder livelihoods, from landscape degradation, dust emissions and water pollution, to a loss of traditional practices, community displacement and corruption.

Oyu Tolgoi’s footprint

The US$12-billion Oyu Tolgoi mine, which means “turquoise hill,” is perhaps the most prominent example of herder-mine conflict in Mongolia. The mine, located in the traditional camel-breeding region of Khanbogd Soum (district), was acquired by Ivanhoe Mines in 2000 and expanded. The Mongolian public’s doubts about the mine first surfaced when Ivanhoe’s president announced to investors the company had found a “cash machine in the Gobi.”

Now majority-owned and operated by Rio Tinto Corporation, the mine is the biggest employer in the district. Even though mining costs recently jumped by almost US$2 billion, Oyu Tolgoi remains Mongolia’s largest corporate taxpayer.

Oyu Tolgoi has impacted the district in many ways. The mine funds a variety of corporate social responsibility initiatives, including a community health program, business training for local entrepreneurs and a project preserving dinosaur tracks in the desert. It has also built significant infrastructure, including graded roads and an airport.

However, much of this infrastructure remains unavailable to herders, or actively inconveniences them. The exclusion zones around the mine site, airport and pipelines have displaced traditional migration routes. Roads have divided and fragmented pastureland, and traffic poses a collision risk to herds. Boreholes built by Oyu Tolgoi may have accidentally connected shallow and deep water aquifers in the region, and may dramatically reduce the availability of shallow groundwater used for animals.

These issues prompted local herders to bring a case against Oyu Tolgoi to the World Bank, leading to a landmark agreement between them in 2017.

Changing priorities among herders

While Oyu Tolgoi’s shadow looms large on the steppe, a variety of social and economic factors unconnected to the mine have also led herders to change their behaviours and decision-making.

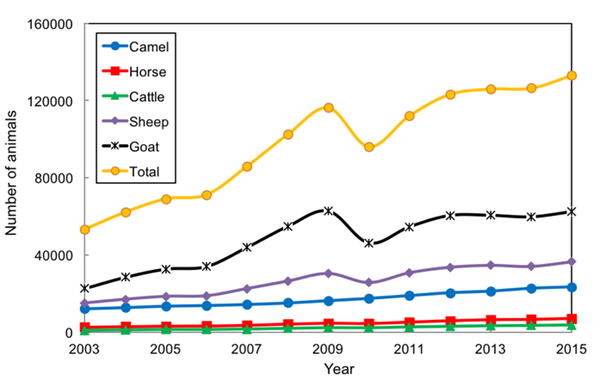

Livestock numbers have boomed since Mongolia’s transition to democracy from 20 million in the 1990s to more than 60 million in the 2010s. This upward trend, which reflects herding’s transformation from a subsistence livelihood to a form of development and wealth, has also been observed in Khanbogd district.

A two-fold increase in animals herded in the district between 2003 and 2015 has placed much greater pressure on water and pasture resources. The poor maintenance of the water wells and limited access to some water points have exacerbated these pressures, and the growing use of motorized water pumps has slowed well refilling.

Pastoralism thus seems to be shifting towards maximizing resource usage for personal advantage, rather than following the customary shared approach to land use. The district government has struggled to respond to this shift as it lacks the capacity or power to address local challenges related to land ownership. In the absence of clear governance, herders have increasingly come to expect Oyu Tolgoi to perform the role of the state and provide infrastructure and services.

Coexistence, survival?

Contrary to common narratives, mining and herding do appear to coexist in Khanbogd district — for now, at least. Herders have strategies to cope with the harshness of the desert, and the rise in animal numbers suggests this remains a viable, if not entirely sustainable, livelihood in the region.

Nevertheless, the continuing evolution of herding away from subsistence livelihoods, combined with the presence of Oyu Tolgoi and other mega-mines, is leading pastoralism into an uncharted future. As China’s US$1-trillion Belt and Road Initiative gains pace, Mongolian herders will have to navigate a complex cocktail of climate change, water risk and pressure from extractive industries and market forces. A point may soon come where traditional mobile pastoralism gives way to more settled animal husbandry, making Gobi life unrecognizable to Marco Polo’s expedition centuries ago.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Author bios

Jerome Mayaud is a Postdoctoral Fellow, School of Community and Regional Planning at the University of British Columbia and Troy Sternberg is a Researcher in Geography at the University of Oxford.