Long before Donald Trump’s malignant narcissism plunged the United States and the world into a hall of mirrors, thought leaders like Christopher Lasch warned about an emerging psychic assault on humanity and a breakdown of culture.

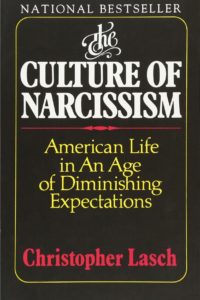

Most of the population had been reduced to incompetence by professional elites, Lasch charged in a controversial book, The Culture of Narcissism, while the family was simultaneously being undermined by advanced capitalism. The personality itself was under attack, he argued, by bureaucracy, a therapeutic culture, and “the domination of our whole experience by fabricated images.”

As Michiko Kakutani explains in a new book, The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump, Lasch was ahead of his time in defining narcissism as a “defensive reaction to social change and instability.” A cynical “ethic of self-preservation and psychic survival” afflicted the nation, Lasch believed. It was the symptom of a country grappling with defeat in Vietnam, growing pessimism, a media culture centered on fame and celebrity, and “centrifugal forces that were shrinking the role families played in the transmission of culture.”

In 1979, shortly before Lasch helped President Jimmy Carter write his memorable, televised “malaise” speech (Carter didn’t actually use the word), I taped and published an interview with the historian about his analysis of contemporary society. “It’s almost as if we can’t experience things directly anymore,” he explained, more than a decade before the Internet went public.

“Something only becomes real when it’s recorded in the form of a photographic image, a recording of the human voice, or whatever. The result is that our whole perception is colored, and I think it has a mirror-like effect. People find it difficult to establish a sense of self unless it’s reflected back in the reaction of others or in the form of images.”

In The Culture of Narcissism, Lasch had extended the word’s definition to include “dependence on the vicarious warmth provided by others combined with a fear of dependence, a sense of inner emptiness, boundless repressed rage, and unsatisfied oral cravings.” He also added secondary traits like “pseudo self-insight, calculated seductiveness, nervous self-deprecating humor… intense fear of old age and death, altered sense of time, fascination with celebrity, fear of competition, decline of play spirit, deteriorating relations between men and women.”

Even more disturbing, he asserted that the narcissistic personality was ideally suited for positions of power, a callous, superficial climber who sells him or herself to win at any price.

Today, all of this rings like a prediction about the shape of political leaders to come.

Since Lasch also argued that capitalism was part of the problem, specifically by turning the selling of oneself into a form of work, I asked him to explain. “Capitalism takes bureaucratic form,” he said. “Advancement and success depends upon the ability to project one’s personality and to project a winning image, rather than competence in any given job. Your own personality becomes the principal resource to be marketed.” Almost 40 years on, this sounds very much like the Trump-ist mindset.

Mass media were largely responsible, Lasch said, since they create both a sense of “chronic tension” and a “cynical detachment” from reality. And it wasn’t just the advertisements. “By treating everything as parody, a lot of TV shows reflect the same distancing techniques,” he explained. “Everything is a put-on, a take-off. And nothing is to be taken altogether seriously. We now have a whole genre that parodies other popular forms, creating a kind of endless hall of mirrors effect. It becomes very difficult to distinguish reality from images. Finally, the distinction collapses altogether.”

Somewhat depressed by this diagnosis, I tried to refocus on the bright side by asking about the difference between the debilitating detachment he had described and a more healthy skepticism.

“A person could even experience both reactions at different times,” Lasch replied. “This raises a very important political question too, because the thrust of institutions might have a very healthy political effect in reducing people’s dependence on big organizations, making people more willing to solve their own problems. But, on the other hand, it has so far expressed itself as a crippling cynicism in the whole political process: no change is possible at all, and all politicians are corrupt.”

Worse yet, he asserted that the modern American family promoted the development of narcissistic people. Many mothers are no longer confident of their ability to raise children, he said, and many fathers no longer have work that provides an example to follow. “The atrophy of older traditions of self-help has eroded everyday competence in one area after another and has made the individual dependent on the state, the corporation, and other bureaucracies. Narcissism represents the psychological dimension of this dependence.”

Popular culture feeds as a parasite on the narcissist’s primitive fantasies, Lasch continued. It encourages delusions of omnipotence while at the same time affirming feelings of dependence and blocking the expression of strong emotion. The bland and empty disco-supermarket-mall-mellow facade of mass existence can be overwhelming. Yet within people there was also enormous anger for which bureaucratic society provided few outlets.

Lasch was expressing harsh and then-contrarian views, some that liberals, conservatives, and even radicals hesitated to embrace at the time. For example, he believed that American society was fast approaching a point of moral dissolution, but charged that both the “welfare state” and permissiveness were among the causes of the impending collapse. At the same time, he saw hope in the potential for resistance among working people who retained religious, family, and neighborhood roots.

One of his targets was the “awareness” movement. In that regard, when I asked what Lasch thought about Erhard Seminars Training (Est), an extension of the human potential movement, he offered that it did have some appeal as an “antidote” to narcissism. Yet his reason was chilling. “It entails a certain amount of arbitrary discipline, a kind of submission to authority that you find in some religious cults, too,” he said. “People who lack meaning and structure are likely to turn to some sort of authoritarian solution.”

In view of this, I wondered where he thought the necessary vision for change would come from. “There is more resistance among people who really don’t have much stake in the present economic system, people who are victimized by it,” he replied. “Their working environment is not invaded by bureaucracy in the same way. And the second thing is that they have some cultural resources, like religion, that help to counteract this. Of course, all these things are often sneered at as evidence of the backward mentality of American workers. We’re going to have to view that in a much more positive light.

“One of the problems I see is an erosion of any sense of moral responsibility. That’s closely linked to the loss of competence. And religion is one impulse that helps to keep alive the sense that people are responsible for what they do. It represents a sort of moral realism that is very important now.”

But the family, church, neighborhoods and institutions were all under assault, Lasch warned. And, although somewhat skeptical about what he viewed as a gradual shift toward state socialism, he acknowledged that “the state is going to have to play a larger role,” particularly in areas like energy and resource allocation.

On the other hand, he also foresaw a risk that turned out to be all too real: that an expansion of the state’s role, combined with exploitation of reactionary tendencies in the family and church, could spark the authoritarian surge he feared.

Greg Guma is the Vermont-based author of Dons of Time, Uneasy Empire, Spirits of Desire, Big Lies, and The People’s Republic: Vermont and the Sanders Revolution. He has been a writer, editor, historian, activist and progressive manager for over four decades, leading progressive organizations in Vermont, New Mexico and California.