Source: Waging Nonviolence

Early mornings in the desert are usually dry, dusty and warm — in the summer, sometimes excruciatingly hot. There was a bit of a wind on the morning of Feb. 26, one that carried a certain sense of foreboding: a nasty sirocco, or sandstorm, was apparently on its way. Still, there was also an anxious anticipation, as an historic resistance action was about to take place.

On the eve of the 42nd declaration of a still-unrecognized Sahwari Arab Democratic Republic, and after 136 years of Spanish colonialism and Moroccan occupation, people from all walks and areas of Western Saharan life were about to assert themselves as a united people by voting in a symbolic but highly representative referendum for full independence as a nation. The people of Western Sahara were not waiting for colonialists, neo-colonists, or an unresponsive global community to grant them what they are in the business of building for themselves.

One shouldn’t have to be a human rights expert, a lawyer specializing in international border policy, or a modern-day Pan-Africanist to know that colonialism has long been declared a crime against humanity. The connections between land, freedom, sovereignty and self determination have been established as universally significant to the life of a people. Since the founding of the United Nations after the Second World War, when questions of extermination and genocide were undoubtedly prescient, subjugated people — imprisoned by external powers and occupying military forces — were given new hope. More than 70 years later, however, only a small handful of concerned people outside of the Sahara region of Northwest Africa seem to care or even know about the plight of the colonized Sahrawi nation.

The dramatic nonviolent action and an accompanying conference at the end of February might begin to change all that.

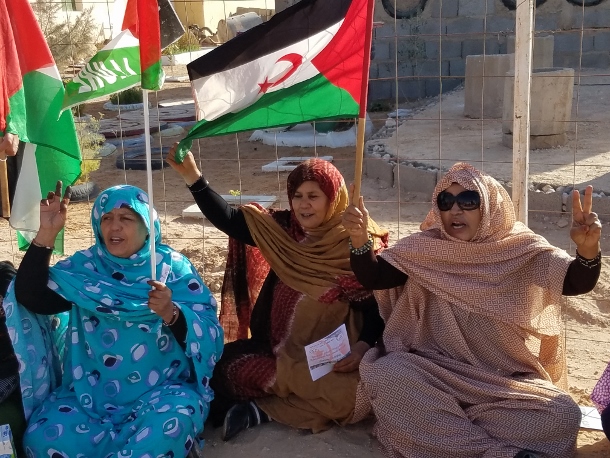

The hundreds who gathered were a tiny cross-section from dozens of affiliated Sahwari organizations, communities and geographic areas. Groups of women adorned in traditional dress sang, shouted and waved the national flag, with the word “Liberty” written across it in Arabic and Catalan. Lines of people from near and far signed in, were handed a voting card, and cast their ballot for a free, independent and united Western Sahara. The action was symbolic and simple, but deeply emotional for all those involved. The referendum results were clear, the international legal and humanitarian consensus is evident. There is just a lack of consciousness outside of the region about these people and their struggle.

In the middle of the desert west of Algeria, in the middle of what many would call nowhere at all (and literally off the map of even progressive cartographers), lies three interrelated yet distinct territories. Western Sahara itself, recognized by the United Nations since 1963 as a non-self-governing territory, is split in two. The majority of it is occupied by Morocco, which has taken total control of its land and natural resources. “The rich Sahawari phosphate reserves were essentially stolen by the Moroccans,” noted legal scholar Magdalene Moonsamy, a former member of South Africa’s Parliament, who also reported that their High Court ruled on February 23 that the valuable minerals now mined by international corporations “have never belonged to Morocco, and are owned by the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic.” Morocco’s exploitation of Western Sahara represents one of the last — and geographically the largest — direct examples of colonialism left in the world.

The second geographic area which is part of Sahwari territory is a liberated zone, governed by the Sahawari liberation movement known as the Polisario Front. Polisario has controlled this rural region since 1975 when Morocco gained military control over all but this section of the Sahawari national land. The liberated zone is largely inhabited by traditionally nomadic people, who join with Polisario combat units to protect the small communities that have developed close to the waterways, which serve as an almost oasis in the desert.

Finally, outside of Western Saharan territory on western tip of the Algerian border, which disputedly belongs to Morocco, is a series of six huge refugee villages, potentially housing more than 100,000 Sahawari people who have been forced off their land. In a stable and supportive relationship between Polisario and Algeria, these lands are run by a Sahawari government structure in exile, the perfect place to hold a large coming together of those living under the occupation, those spread out in the diaspora, those living in the camps themselves, plus a few international solidarity workers. Perhaps the most historic aspect of the resistance referendum was the coming together of all of these groups in a united, national display.

NOVA, a youth movement committed to nonviolence made up of Sahawari activists across these borders, has emerged as a major force of change throughout the region. “Our strategy is to continue the peaceful struggle which began at the very beginning of colonialism and continues right up to today,” stated Maglaha Hamma, president of NOVA, at the opening session of the Sahara Rise conference, which took place in the refugee village of Smara from February 25-27.

The conference included Polisario leadership and a broad cross-section of Sahawari civil society, and focused on building coordination of a global work plan of civil resistance. Brahim Dahane, a former political prisoner still living in and representing Sahwaris under occupation, asserted that “one of the greatest victories of peaceful resistance has been our ability to speak as one people, empowered to build bridges” across borders.

Mohamed Elouali Akeik, the Polisario Minister for the Occupied Territories and the Diaspora, echoed that perspective, emphasizing that the essential goal of the resistance is to “regain the rights of all of our identity as a people.” Noting that resistance was growing significantly every day, Elouali Akeik said that “we are all prisoners so long as there are any prisoners,” and added that all those concerned with human rights must “oppose the legitimacy of Morocco’s occupation by all peaceful means.”

It is noteworthy that all sectors of Western Sahara society make little distinction between the significance of the armed actions of the past and the embracing of radical nonviolence today. There are no significant divisions between peoples and groups based on these different approaches and ideological strains. As one local Smara activist put it, “we started with armed resistance and have now come to peaceful resistance. We have a huge heritage of resistance.”

That resistance will surely continue to take many forms, and has already included numerous acts of creative civil disobedience. Elder organizer Deida Uld El Yazid, known as the Sheikh of the Intifada for his participation in countless sit-ins, protests and meetings, was one of the first to pull together the 30,000-person Gdeim Izik encampment of 2010, taking back a small part of the land that had long been Sahwari. A new generation, dynamically committed to building across Pan-Arab and Pan-African lines, had already taken the lead by the time of El Yazid’s death in January 2018.

Abdeslam Omar Lahsen, the coordinator of the Sahara Rise action and conference coordinator is one such leader. He was also a co-founder of the Pan-African Nonviolence and Peacebuilding Network in 2014, which shares best practices and support to its affiliates in 35 countries from every region of the continent. At Sahara Rise, the spirit of solidarity with the ideals of peaceful change and Sahwari independence was evident, especially from neighboring Tunisia, which was represented in part by the recent Nobel Peace laureate organizations whose fundamental principles include dialogue and coalition-building. Tunisian organizer Inis Tlili, who works with NOVACT, the International Institute for Nonviolent Action, put it this way: “One of the main advantages of nonviolent resistance is that it opens the door for the participation of everyone!”

Well into the night, with fears of a worse storm in the days to come, the Sahwari activists discussed strategies and tactics. These included potential plans for a major boycott and divestment effort spotlighting the Moroccan occupation; for human rights campaigns focused on the repression and political imprisonment faced by many of their human rights defenders; and for increased work around the protection of natural resources. Through it all, the sentiments expressed by National Union of Sahwari Women leader Fatma Mehdi summed up the mood and understanding: “Organization is a crucial factor in resistance!”

Matt Meyer, in addition to being the current national co-chair of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and a former chair of the War Resisters League, is the UN representative of the International Peace Research Association. Author and editor of nine books, he contributed to both of Oscar Lopez Rivera’s titles: “Between Torture and Resistance” and “Cartas a Karina.” Meyer was a leading figure in the international aspects of the Campaign to Free Oscar. He is also a senior research fellow with the University of Massachusetts Amherst Resistance Studies Initiative.