Author Diego Cupolo will be speaking at the Fletcher Free Library in Burlington, VT on Tuesday April 29th at 6pm for On the Ground in Syria: Discussion on the Roots of the Conflict and the Refugee Crisis.

All photos by Diego Cupolo

More than three years have passed since protesters took the streets in Syria. What began as a call for democracy, a mass movement to end Bashar al-Assad’s 43 years of family rule, has turned into a foreign-funded proxy war without a foreseeable end.

So far, the war in Syria has produced an estimated 150,000 casualties, displaced about 9 million people and reignited a polio epidemic among children, all while threatening to destabilize the entire Middle East with the rising number of extremist militants being drawn to the conflict. The consequences of the Syrian war have been undeniable, yet questions remain over what accountabilities and responsibilities, if any, fall upon western nations.

With these thoughts in mind, I visited the Turkish-Syrian border for six weeks in the summer of 2013 to volunteer at a Syrian refugee school with my partner, Alice Bernard. The core problems Syria faces today are the same it faced during our visit; the main difference is their severity has increased as refugees continue leaving Syria, overburdening neighboring countries, while jihadist rebel fighters continue entering Syria with the hopes of establishing an Islamic state. The longer the war continues, the worse both situations will become.

Alice and I worked in a small town called Reyhanlı just as outflowing refugee numbers spiked in June 2013. During our stay, we would analyze the war by collecting personal accounts from civilians pouring across the border. Considering that the international debate towards Syria has changed little over the last year, I am now sharing our experience in effort to provide insight on the war and, with hope, provide some guidance for the ongoing discussions on how best to approach the conflict as it rolls into its fourth year.

Alice and I worked in a small town called Reyhanlı just as outflowing refugee numbers spiked in June 2013. During our stay, we would analyze the war by collecting personal accounts from civilians pouring across the border. Considering that the international debate towards Syria has changed little over the last year, I am now sharing our experience in effort to provide insight on the war and, with hope, provide some guidance for the ongoing discussions on how best to approach the conflict as it rolls into its fourth year.

One mile to Syria

Two car bombs went off in the center of Reyhanlı one month before we arrived. The taxi driver pointed out the blast sites, a cluster of charred, windowless buildings surrounded by construction barricades. He said 50 people had died, 140 were injured. It was “the worst terrorist attack in Turkey’s history,” the media claimed.

We got a first-hand account from Hussein haj Ahmad, an English teacher from the Idlib region who would become our main interpreter in Reyhanlı. Not only did he escape Syria under government bombardment, but he was sitting at a café in Reyhanlı’s town center, sipping tea when the two car bombs exploded. Hussein fled the scene so fast he lost his sandals and ran barefoot over broken glass. He still had the scars to prove it.

Once we left the center and its blackened buildings, the taxi driver turned left and we headed towards the edge of town until we reached Al Salam school – or “Peace” school – a Canadian-funded institution for Syrian refugees less than one mile north of the Syrian border.

Alice and I entered the front office, a room with one computer surrounded by mostly empty shelves, and it was there that we would meet our first student. The young boy balanced himself on two crutches as he shook my hand. There was a scar on his cheek and when I looked down I saw one of his legs was missing from the waist down. A missile struck his home in Syria. He was 12 years old.

Alice and I entered the front office, a room with one computer surrounded by mostly empty shelves, and it was there that we would meet our first student. The young boy balanced himself on two crutches as he shook my hand. There was a scar on his cheek and when I looked down I saw one of his legs was missing from the waist down. A missile struck his home in Syria. He was 12 years old.

The boy’s eyes were bloodshot. He didn’t seem to get much sleep, but his face brightened when he asked us to play soccer. We agreed and spent the next 20 minutes kicking the ball around the school courtyard. He proved to be fairly agile with his crutches.

“We want to provide a place for the children to learn, play and feel safe after so many years of war,” Hazar Al-Mahayni, co-director of Al Salam school, told us via Skype that afternoon. “Some of them have seen terrible things and we just want to help them cope with those experiences by giving them a safe place to be children again.”

Hazar explained that our main responsibility at Al Salam was to organize activities for the students – sports, arts, whatever we could think of to “help them forget the war.” She spoke to us from her living room in Montreal where she ran the school by night and worked as a pharmacist by the day.

Hazar went on, saying few people paid attention to Reyhanlı before the war broke out. The small farming town was barely known as an exporter of watermelons and cucumbers when refugees began crossing the border. International aid groups and 24-hour media coverage soon followed as new hospitals opened to treat wounded soldiers and civilians fleeing the violence. Within a matter of months, the town’s population doubled. Its rents quadrupled. Locals profited heavily from the influx of Syrians in need.

To complicate matters, children made up more than half of the total Syrian refugee population, only heightening the need for education centers in dense refugee areas such as Reyhanlı. When Al Salam school opened in October 2012, Hazar said she had enough space for 300 children. To her surprise, more than 900 children showed up. She accepted them all and ran two full school sessions – one in the morning and one at night. Today, the school building is undergoing construction for a second floor expansion and currently educates 1,200 children.

The introductory conversation then turned to the recent car bombs in the town center. Those responsible for the attack were never identified. It could have been a number of groups on both sides of the border, but infuriated locals blamed Syrian refugees for bringing the war across the border. Cars with Syrian license plates were vandalized, their windshields smashed, and anti-Syrian threats were spray painted on walls as Syrian families were told to leave the town.

Our interpreter, Hussein, did not leave his apartment for 10 days after the explosions. He stayed inside, without food, out of fear for being attacked by angry mobs. The protests were subdued only after Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan visited the town, insuring residents they would be reimbursed for their losses while reaffirming that Syrian refugees would be welcome in Turkey as long as fighting continued across the border.

This was the context under which we would work.

“You come from a democracy”

Over the next six weeks, Alice and I organized a variety of activities for the students using the school’s limited resources and our limited Arabic. Together we made arts and crafts, created recycling and waste awareness programs, invented sports and planted vegetable gardens.

Over the next six weeks, Alice and I organized a variety of activities for the students using the school’s limited resources and our limited Arabic. Together we made arts and crafts, created recycling and waste awareness programs, invented sports and planted vegetable gardens.

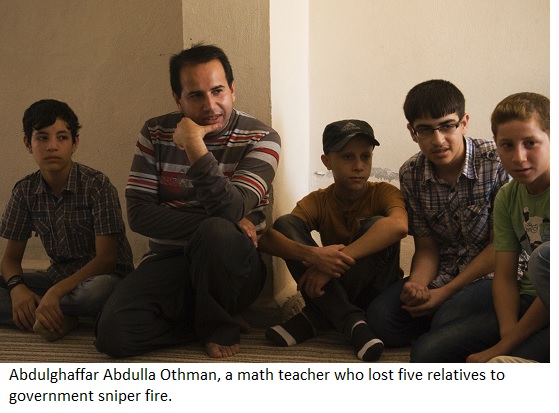

Still, it was the school’s math professor, Abdulghaffar Abdulla Othman, who would propose the most compelling project we undertook at Al Salam. He wanted to teach students about democracy: what it means to vote, to choose leaders, to organize elections.

“You come from a democracy,” he told Alice and I. “You can teach the students how elections work because we never had real ones in Syria. When this war is over, we will have a democracy in Syria and the younger generations need to know how to vote.”

To achieve Abdulghaffar’s vision, the three of us organized student council elections. Each grade level would vote for two representatives and, in the process, learn about democracy. Students made speeches, campaign slogans and promises to better the lives of their fellow classmates.

Throughout the project Alice and I worked closely with Abdulghaffar, often planning the elections from his home as Hussein translated our conversations. Sitting over a never-ending stream of tea, we learned Abdulghaffar had worked for the UN in Palestine. He was also in the Syrian military at the time when the uprisings began, serving his mandatory duty as an accountant. He remained at his post as long as he could, but fled after government forces killed his brother-in-law. His wife was pregnant with their first child and he wanted to find a safe place for his family.

“They hang soldiers that abandon the Syrian army,” he said. “ I would’ve been killed if they found me so I travelled to Reyhanlı alone. My wife and family joined me here about a month later.”

But some never made it. Five of his relatives died by sniper fire before they could leave Syria.

“They weren’t even protesting,” Abdulghaffar said. “My cousin was shot while he was painting a house in the middle of the day. He was standing on scaffolding and fell after the bullet hit him. He was just working. “

“His father was also shot to death on the same day,” he continued. “He was sitting in his house, watching television when a bullet came through the window. The Syrian Army kills for fun. Violence is just a game for them.”

“His father was also shot to death on the same day,” he continued. “He was sitting in his house, watching television when a bullet came through the window. The Syrian Army kills for fun. Violence is just a game for them.”

Yet for many Syrians, the violence began long before the Arab Spring of 2011. Opposition to Hafez Al-Assad’s Ba’ath Party peaked in the early 1980s, resulting in the Hama Massacre of 1982 where government forces occupied the city for 27 days, causing 20,000 to 40,000 deaths. An accurate figure will never be known as many residents were imprisoned and died in one of many political prisons.

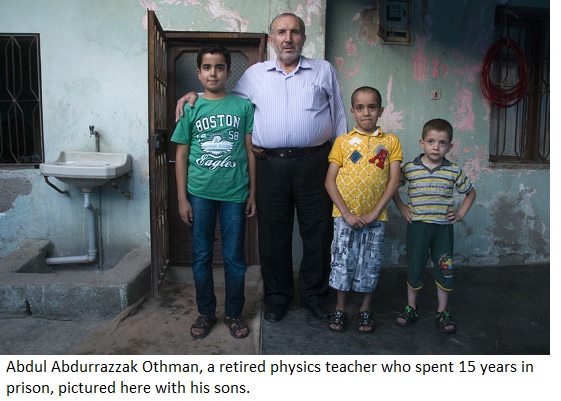

Abdulghaffar’s uncle was one of the few prisoners that made it out. In 1981, he was jailed for having friends in Syria’s Muslim Brotherhood. Though his uncle was an apolitical high school physics teacher, he would spend 15 years of his life in an underground prison where he was tortured on a daily basis.

His name was Abdul Abdurrazzak Othman and he had also taken refuge in Reyhanlı. When he heard Alice and I were collecting accounts from Syrian refugees, he invited us to his apartment.

“They kept us underground”

In what became the longest four hours of my life, Abdul calmly described every single torture technique inflicted on his body as Hussein translated in horrific detail. At one point, Abdul pulled down his pants to show us a gap in his upper thigh, a missing piece of flesh from his leg, where he was repeatedly beaten with wooden rods over the years.

“They always hit me here,” Abdul said. “One military commander would watch while two or three guards beat me with the sticks. The commander was there to instruct them where to hit me. Usually he would focus the blows on one part of my body. Create as much pain as possible.”

Abdul insisted we hear his stories to show the extent of oppression and brutality some Syrians had endured under al-Assad’s Ba’ath Party.

“They kept us underground, between one hundred to two hundred men in each prison cell. No windows,” he said. “We could barely breath. The air was so thick we made a rotation. Each man would get one minute to lay down by the entrance and breath the air that came in through the crack under the door.”

When I asked him how he made it out, how he coped emotionally with the circumstances, Abdul did not understand the question. I rephrased the sentence, but he still wasn’t sure what we were asking.

“Allah,” he said, pointing to the sky. “What do you mean by ‘emotional pain?’”

“Allah,” he said, pointing to the sky. “What do you mean by ‘emotional pain?’”

He was clear. There was no room for weakness in those prison cells and to this day, Abdul’s jail, better known as Tadmor prison, remains open for government adversaries.

His was one of many stories we gathered during our time in Reyhanlı. With the help of Hussein and Hazar via Skype, Alice and I interviewed a former soldier that watched his best friend bleed to death in his arms. We spoke with a young woman who fled Syria on foot, crossing desert mountains into Turkey with her family after being put on a government “black list.”

We listened as a young man described jumping from rooftop to rooftop, avoiding sniper fire as armed forces occupied his hometown. Hussein, himself, had spent 45 days in cave with a broken leg, watching from a distance while his town was destroyed by air raid after air raid.

Alice and I also interviewed Lieutenant Ahmad al-Soud of the Free Syrian Army, the secular rebel group that was fighting Assad to establish democracy in Syria. Reyhanlı was known to serve as a refuge for rebel fighters seeking rest or medical attention between military assaults and we found the lieutenant standing outside a local hospital after visiting his wounded soldiers.

Speaking sharply and glaring at us through his dark eyes, Al-Soud said religious extremists were gaining momentum in Syria. The longer the war went on, the more powerful Al-Qaeda-style rebel groups would become.

“Russia, Iran and Hezbollah are helping Assad, but no one is helping the resistance,” Lt. Al-Soud said. “Think about it. Our people have been at war for more than two years now and if someone, anyone, offers them help, of course they’re going to take it. The trick is that if you receive arms from Al-Qaeda they will make you work for their organization. That’s how the recruitment process starts.”

He also said whatever we read in the news was false. Reporters had no idea what was going on because the army generals they interview barely understood the war. There were too many separate parties with conflicting interests in the war and the Free Syrian Army was being fired upon from all sides.

Soon after the interview, Lt. Al-Soud returned to the front lines in Idlib where he led a unit of more than 3,000 soldiers. Six months later, he would be kidnapped by a jihadist rebel group. It is unknown whether he is still alive.

“We were fighting for democracy”

“Terrorists hijack not only planes, but revolutions,” said Muhammad Hallum, a 23-year-old Syrian peace activist who had been part of the initial street protests. “We were fighting for democracy, but now it seems we’re fighting for religion.”

“First, my region was occupied by the Syrian army, then when they left, the Al-Qaeda groups took over,” he added. “They say they are Muslims, but I don’t think so. Islam, in its roots, is peace.”

The Syrian conflict, like similar uprisings that took root during the 2011 Arab Spring, began as a civil war between an oppressed population and their ruling dictator. Since then, the war has become a stalemate, drawing involvement from neighboring countries, as well as, foreign Al-Qaeda-style networks and Kurdish militias who entered the conflict with intentions of forming new nations for their ethnic groups and followers.

The Syrian conflict, like similar uprisings that took root during the 2011 Arab Spring, began as a civil war between an oppressed population and their ruling dictator. Since then, the war has become a stalemate, drawing involvement from neighboring countries, as well as, foreign Al-Qaeda-style networks and Kurdish militias who entered the conflict with intentions of forming new nations for their ethnic groups and followers.

Currently defined as a regional proxy war divided along Sunni-Shiite lines with implications that could reshape regional and international politics, the Syrian conflict has no clear solutions and, regardless of the outcome, it is Syria’s youngest generations that will suffer the war’s greatest impacts.

Abir Hashem, a first grade teacher at Al Salam school, told us many of her students would be permanently scarred by their experiences.

“The influence of war has been too heavy on the smaller children. They are young and they relate everything to violence,” Abir said. “When I draw pencils on the board, they see missiles. When I draw a cloud with rain drops, they see a plane dropping bombs.”

“I am like any human being,” she continued. “Maybe I look strong when I stand in front of the classroom, but most of the time I am trying not to cry. The children tell me so many stories. How their fathers died, how they lost their friends, everything. They are so small.”

Throughout our stay, Alice and I worked with countless children that never attended school in their lives. Three years of war has interrupted primary education for younger students and when they crossed the border into Reyhanlı, many arrived filled with anger, confusion and aggression.

Fistfights were not uncommon in the courtyard. Antisocial behavior was also prevalent. When given crayons, some children would draw tanks destroying houses and cities filled of fire, but these weren’t imaginary scenes of war, the children were drawing their houses and their cities filled with fire.

One student, a seven-year-old boy, had the unfortunate experience of being home when government forces broke in to gather intelligence. He was forced to watch as soldiers interrogated and tortured his uncles, killing one of them in the process.

We never knew what the students had experienced before arriving in Reyhanlı, but Alice and I noticed the school environment had a positive effect on the refugee children. The longer students attended Al Salam, the more they calmed down and the more they became children again, which was Hazar’s ultimate goal in founding the institution. Al Salam school provided a much-needed safe haven for the young refugees to socialize, run freely and, most of all, play.

Leaving Reyhanlı

Today, after more than three years, the Syrian war could easily drag on for another five to ten years. Where there’s a weapon, there’s a will and new fighters will replenish the old ones as long as foreign powers supply ammunition and funding.

Several thousand soldiers of European, North American and Asian origin are currently fighting in Syria, some joining jihadist militias without speaking a word of Arabic. On Bashar’s end, Putin, the Iranian government and Hezbollah are not likely to downgrade their support any time soon. Meanwhile, the secular Free Syrian Army seems weaker than ever before.

Several thousand soldiers of European, North American and Asian origin are currently fighting in Syria, some joining jihadist militias without speaking a word of Arabic. On Bashar’s end, Putin, the Iranian government and Hezbollah are not likely to downgrade their support any time soon. Meanwhile, the secular Free Syrian Army seems weaker than ever before.

At the same time, the war has displaced nearly half of the Syria’s population. Lebanon, a small country teetering on the edge of civil war, recently registered its one millionth Syrian refugee.

As of March 2014, Turkey has taken in more than 600,000 Syrian refugees. Jordan has almost the same amount. At the moment, the war has caused the largest refugee crisis since the Rwandan Genocide in 1994. Yet the same question remains today as when I left Reyhanlı in July: What is the West’s responsibility regarding the Syrian war?

Syria provides a new test for moral and security dilemmas that have faced western nations in the past. While military intervention is not likely to produce better results at the moment – nor is it warranted – perhaps the international community has an obligation to better assist Syrian refugees and increase humanitarian aid to camps in neighboring countries.

Still, material support is only one part of the equation. Many Syrian refugees told us they simply wanted to be acknowledged. Like Rwandans 20 years earlier, they felt abandoned by the international community as armed militias have overtaken their country and commit war crimes without consequences.

The war may be occurring on Syrian ground, but the battle lines represent a larger regional conflict between Sunni and Shiite ideologies, between Saudi and Iranian dominance. From beginning to end, it is the Syrian civilian who bares the weight of this war. On one shoulder stands Saudi Arabia, the United States, Turkey and Qatar while the other holds Iran, Russia, Hezbollah and China. If and when these stacks fall and military intervention is undertaken in Syria, the question remains: Where will the Syrian civilian stand when the dust settles?

Diego Cupolo is an international journalist, photographer and author of Seven Syrians: War Accounts From Syrian Refugees, (8th House Publishing). He serves as Latin America regional editor for Global South Development Magazine. See more of his work at www.diegocupolo.com.