This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

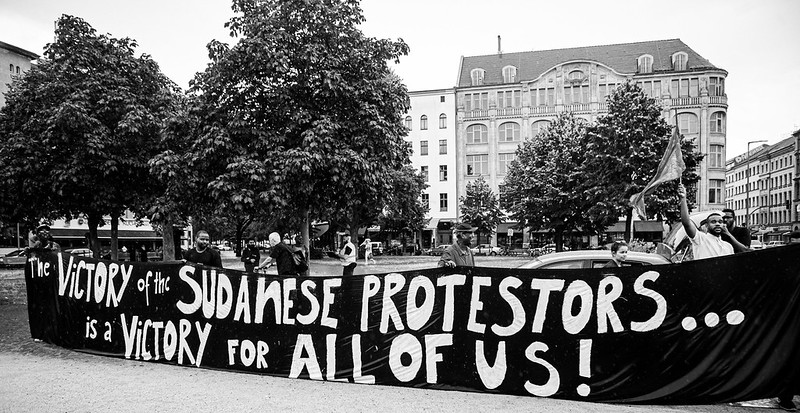

In the last few weeks, tens of thousands of people have, once again, taken to the streets of Sudan’s major cities to demand “freedom, peace and justice,” the rallying cry for the protesters who ousted Omar al-Bashir in 2019.

The big difference is that this time they are marching against the civilian-military Sovereign Council, demanding a greater role for civilians in the country’s transition towards democracy and faster reform.

A year ago the people of Sudan were heralding the fall of Bashir, the country’s long-serving strongman. A mass uprising led by the Sudan Professional Association and Resistance Committees had eventually managed to precipitate the deposing of the president. A host of grievances fanned the protests. Among them were endemic corruption, a struggling economy, human rights violations, and a failed health system.

Why then have the protests returned to the street so soon after they vacated them in triumphant euphoria?

The answer lies in the fact that the balance of power in the transition period that follows the fall of a despot is always tricky. This was evident in Tunisia, Algeria and Egypt. When reformers are relatively weak and those determined to protect the status quo are strong, substantive change will be demonstrably lethargic and long-winded. It will sometimes be stalled, and even reversed in certain instances.

Entrenched status quo elites will be reluctant to change because this poses a threat to their interests.

Events in Sudan point to this tension.

What’s been done

Following Bashir’s ouster, a civilian-military sovereign council headed by a civilian prime minister, Abdalla Hamdok, and made up of six civilians and five military officers, was instituted. Its immediate challenge was ensuring security and stability, negotiating peace with Darfur rebels, and repairing Sudan’s battered economy.

So what is on its report card a year on?

For starters, the systematic jailing of opponents has stopped, and arbitrary arrests from the security bureau have largely ceased. Censorship and the muzzling of the press has all but stopped. And the public order law has been repealed. This law was notorious for giving police disproportionate powers of arrest and punishment including for moral and religious infractions.

In rebuilding institutional trust, the police chief and his deputy have also been fired, after protesters demanded more measures against officials linked to Bashir.

In addition, serious effort have been made to meet another core protest demand – the end to incessant conflicts in Sudan. Peace efforts have been pursued with the rebel Sudan Revolutionary Front. These efforts produced a preliminary peace accord, including the drawing down of the UN peace keeping mission in Darfur.

Most recently, an anti-corruption body to trace ill-gotten wealth and provide accountability has been set up. The confiscation of almost $4 billion of assets from Bashir, his family and associates signals a move in the right direction.

In addition, the transitional government has actively sought to change Sudan’s standing in the world by shedding its image as a pariah state. This was not of primary concern to the protest movement, which was focused more on issues of bread and butter. But the transitional government nevertheless has acted to mend fences in the hope that it will deliver dividends for the country.

To this end, it has actively lobbied the US government to remove it from the list of state sponsors of terrorism. Washington is still considering this request. In the meantime it has removed the country from a black list of states endangering religious freedom. It has also lifted sanctions on 157 Sudanese firms.

And, for the first time in 23 years, the two countries have exchanged ambassadors.

For its part, Sudan has reduced the number of troops it has in Yemen by two thirds.

What’s missing

But the expectations of last year’s popular uprising have not been met. The reason for this is that substantive reforms have been slow.

One area of clear frustration has been the snail’s pace at which civilian control is taking place. The civilian governance footprint on the country’s body politic is not yet evident. Instead, the military elite continues to have de facto control and influence, sidelining the civilians and often pushing for greater compromises from civilian partners.

Examples of this include the fact that a legislative transitional council has yet to be installed. This would have provided a degree of counterweight to the military dominated sovereign council. Legislation is thus being done in an ad hoc manner.

In addition, civilian governors haven’t been appointed to replace military ones in the various provinces, which would signal another move away from military governance.

The lack of urgency in bringing Bashir and his henchmen to trial is also frustrating people. It appears to be a marginal priority, and in some instances deliberately frustrating.

Nor have the country’s economic woes been addressed. People still queue for three to six hours to buy bread, or fill their tanks at petrol stations. Electricity reliability is still sketchy, with power cuts the norm. Accessing domestic gas is also a problem.

The economy has been contracting and oil revenues have slumped due to falling oil prices and low production capacity. This has affected public expenditure and the investment needed to jumpstart the economic recovery.

COVID-19 has done even more damage.

What’s holding back reforms

Sudan has competing power structures that are inhibiting coherent and far reaching reforms. In the one camp are the reformers, in the other those who wish to defend the status quo. Reformers are constantly having to negotiate and make strategic calculations about what changes can be made and how fast.

This game of political brinkmanship is beginning to take its toll.

Clearly the civilian half of the transitional government has struggled to assert or leverage its moral authority or “popular legitimacy” in the face of military intransigence.

But the prime minister Abdalla Hamdor remains popular. In seeking to placate the demonstrators, he recently admitted that the transitional authority had to “correct the revolution’s track”. This was tacit acknowledgement that on his watch things have gone off the desired path.

But does he have the leverage to correct this diversion from the expectations of the street?

That answer might sadly be, not to a great extent.

For now, the reality that the protesters and civilian elite have to contend with is that after a long and destructive authoritarian legacy, change will not come easily. Nor can it be fast-tracked. Rather it is a product of patience, compromise – and above all perseverance.![]()

Author Bio:

David E. Kiwuwa is Associate Professor of International Studies at the University of Nottingham.