In 1992 the Union of Concerned Scientists issued a warning to humanity. They cautioned that the current trajectory of development promised vast human misery that would leave our planet irretrievably mutilated. As we all know, this warning was not heeded.

In the wake of Climate Walk Out this year, CNN’s Climate Debate and Democracy Now’s First Presidential Forum on Environmental Justice, the future of humanity hangs in the balance. But the environmental costs of constant war have not been adequately considered.

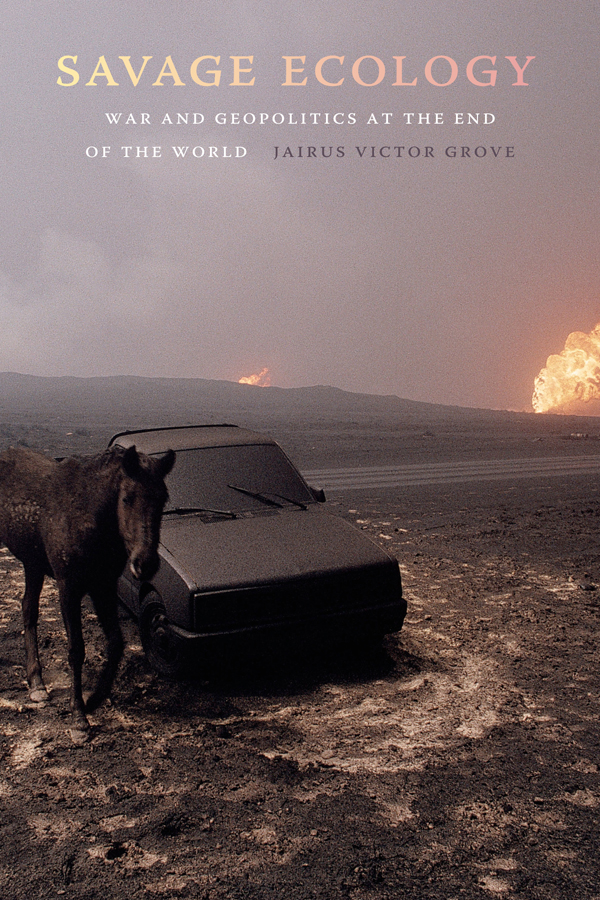

Jairus Victor Grove, Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Hawai’i, Manoa, and Director of the Hawai’i Research Center for Futures Studies, explores the environmental impacts of war in his book, Savage Ecology: War and Geopolitics at the End of the World.

The book’s title critiques the narrow focus of the climate change movement, where the default approach puts the onus for reducing carbon in the atmosphere on individuals rather than on the corporations that have caused it. This hyper-individualist approach is radically antagonistic to collective survival, and erases the U.S. role in building and maintaining the current world order in which not all of us have played an equal part in creating the climate change crisis.

“The violence of geopolitics is an ecological principle of world-making that renders some forms of life principle and other forms of life useful or inconsequential,” writes Grove. Savage Ecology begins with a discussion of Paul Crutzen, a Dutch, Nobel Prize-winning, atmospheric chemist, who coined the term Anthropocene. Grove prefers to talk about a Eurocene, which is dominated by the 100 corporations that are responsible for 71 per cent of global emissions.

Grove positions the U.S. as one of the world’s leaders in abusing the environment and not taking strict measures to curb climate change. At this year’s COP 25, the UN Climate Change Conference, “more than 70 developing countries have announced they will accelerate their climate plans, and 72 countries have signed onto goals to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050. But major emitters Australia, China, India, Brazil and Saudi Arabia have made no such promises, while the U.S. is slated to pull out of the Paris Agreement entirely by next year,” according to Democracy Now!

In Savage Ecology, Grove crystallizes the attitude of “developed” nations such: “Geopolitics as a European-led global project of rendering, in the way that fat is rendered into soap, or students are rendered pliable and obedient subjects, is the driver of our epoch and the obstacle to any other version of our world, whether plural or differently unified.”

Grove situates war as a constant force of the Eurocene, stemming from annihilation practices of settler colonies that continue to govern our bodies into the present. He notes that the U.S. military is the world’s single largest consumer of oil, while the richest 10 percent of the population produce fifty percent of global carbon emissions.

Savage Ecology goes on to consider a case study of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and the decisive role they played in the U.S. led, post–September 11, 2001, wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Grove considers IEDs as larger manifestations of war where innocent Iraqi and Afghani civilian lives are reduced to equations of refuse as collateral damage. Grove draws on WikiLeaks data to show the U.S. planted enough landmines in Iraq and Afghanistan to kill one third of the population of both countries.

But IEDs are also part of a global flow of waste, combining “with the deluge of electronic waste shipped, dumped, and smuggled throughout the Global South.” This spread of toxicity is evidenced by the 2004 bombing of Fallujah in Iraq by the US, which used white phosphorus, a toxic chemical agent. The region continues to experience high cancer rates and birth defects and now includes Yemen, a country whose citizens are enduring a genocidal crisis induced by U.S.-backed Saudi coalition’s airstrikes.

Savage Ecology explores the metaphor of a nation’s “life blood,” looking at blood transfusions and their regulation during World War II in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. Grove looks at the ways in which those policies inform the complexity of enmity and blood use in U.S.’s global war on terror, correlating the availability of blood banks to preparedness for war.

After the 1942 discovery of albumin, a base for human blood plasma that can be collected in powder form, blood became a strategic reserve that had to be maintained and sufficiently stockpiled to guarantee military readiness. “The closely guarded secret of when D-Day would commence was inadvertently announced by the scramble to gather sufficient blood,” he writes. Grove then uses the trope of the body and applies the concept of the Eurocene to the neuro-geopolitics of hacking the brain as a new frontier of ecological and martial control.

Since their inception, Euro-American technology companies have been connected to war industries. And though Grove sketches the corporate connections, he doesn’t name names in the book, even though the information would have enriched the text.

For example, Palantir, Peter Thiel’s data-mining firm, began post 9/11 and was incubated by CIA homeland security investments and contracts; Microsoft has a data storage contract for $19.4 million with Immigrations and Customs Enforcement. Amazon sold its powerful facial-recognition tool, Rekogniton, to over 601 police departments around the U.S., and for more than five years, the retail giant has provided the computer backbone for the CIA’s drone strikes. Google’s Project Maven has built Artificial Intelligence that helps military drones recognize objects in flight and most recently, Microsoft secured a $10 billion Department of Defense military cloud contract known as Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI).

These technology companies strengthen the power of the U.S. military at a global scale, and, as Grove underlines, constant war increases the constant production of refuse: the shells of military tanks, IEDs, and bombs that kill innocent people also degrade the environment.

Grove goes on to connect the global geopolitics of the Eurocene to three imagined futures: doubling down on modernity through industrial liberalism, left and right accelerationism through a global Marxist project, and an American military vision of a containable world, under the U.S. Department of Defense.

Savage Ecology posits that the world is becoming more homogenized. These three extreme scenarios are case studies of the current forces at work, in which “coalitions committed to transforming the planet are redoubling their efforts.” And although Grove explores how the weight of the Eurocene in molding the world, non-English speaking, Black and Indigenous perspectives are not given serious consideration.

Savage Ecology also explores the possibilities for forms of life outside of war. For example, the author documents how ecological transformation following the Ice Age is linked to European colonialism and slavery in the Americas, he also connects these social and ecological histories to the formation of the Eurocene. “Euro-American humans are in large part fighting to continue exactly as we are,” writes Grove. Unchallenged U.S. hegemony and imperialist practices abroad are cut from the same cloth as the logic that led us to the climate crisis in the first place.

In an unusual turn towards the horror genre, Grove assembles the profile of the “freak” as endemic to the future existence of humans–taking apocalypse as a fact–and sketches the probable world if it continues along the same sadistic Eurocene geopolitical lines. “Freaks live among us as horizons or closures to a world of possibility between the normative somatic human and the monster,” he writes. Extending Grove’s analysis, in a racist world, whiteness is linked to humanness that demands an utmost level of care and respect, while non-white communities are deemed outliers.

Savage Ecology makes it clear that we need to seriously take stock of the future impact of corporate power linked to Euro-American war machines. However, it does not account for non-Euro-American forms of supremacy such as Sino or Saudi.

The strength of Savage Ecology lies in considering the Euro-American military assemblages and their devastating impacts on the environment. That strength is compromised, however, because the experiences of Black, Indigenous, and communities of color in the global South, who have lived many centuries cohabiting with their environment, are not meaningfully included.

Communities in global South are more likely to becomes refugees due to the climate crisis. Far from being ignored, their voices should be acted upon now.

Author Bio: