Looting has been in the news recently, part of the narrative of the massive Black Lives Matter and anti-police brutality mobilizations that shook the United States during the spring and summer of 2020.

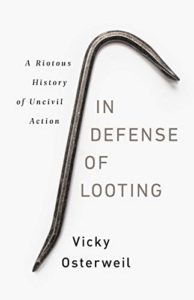

The act of looting is overwhelmingly cast in a negative light by the corporate media, part of an overall effort to demonize militant protests & riots. Vicky Osterweil’s new book In Defense of Looting: A Riotous History of Uncivil Action looks at looting in a number of radical ways.

If you are looking for a study of looting throughout history and throughout different parts of the world, this is not the book for you. Osterweil focuses almost exclusively on the United States and centers chattel slavery and Black resistance, providing an excellent analysis of how white supremacy has fundamentally shaped the US and how it continues to function today. We don’t get much information on looting by, say, English peasants in the middle ages; or escaped Roman slaves looting the estates of their former masters. In short, this is not a history book about looting down through the ages.

Osterweil defines looting as a crowd openly & directly seizing goods, or to be more precise, property. While this most often occurs during some type of riot, Osterweil greatly expands this definition in the opening chapters of the book where the concept of property is closely examined. From this standpoint, she presents a compelling case for considering the escaped African slave –and revolts that saw tens of thousands of slaves free themselves– as a form of looting, which she calls “looting emancipation.”

In Defense of Looting overturns the standard reading of the US Civil War, most often presented as a war to “end slavery,” and shows us instead that it was African slaves who freed themselves in an act of “mass looting” of their own bodies, withdrawing a massive source of labor for the southern states and enabling the northern Union Army to defeat the Confederate forces. In addition, tens of thousands of these former slaves joined the Union Army and greatly bolstered its ranks. Osterweil writes:

From 1861 to 1865, five hundred thousand slaves escaped the plantations, throwing down tools and often crossing Union lines to emancipation. As many as two hundred thousand of them served in the Union Army. It is this incredible act of revolution that would both decide the war and give it its meaning.

The centering of slavery and resistance against it continues in the chapter “All Cops are Bastards,” which traces the origins of US police to early slave catchers and the presence of large numbers of Black people, both enslaved and freed, in urban areas. Here, Osterweil links property and the role of police in protecting that property to the broader concept of looting.

Osterweil does not romanticize looting or those who partake in rioting, which she sees as a powerful tactic, a “common political tool [which] can be used for many different political aims…”

As a counter-balance to the racist media narrative of Black looters, the chapter “White Riot” looks at riots and looting carried out by mobs motivated by white supremacist terror. Still focused on the enslavement of Black people and the Civil War, white riots that occurred in the post-Civil War era and through the decades since are the focus of this chapter.

Osterweil finds that in the first few decades after the Civil War, white riots were often related to lynchings of Black people, but that as more Black families migrated northward, racist riots became the dominant form of mob action in the US. And white rioters did not, for the most part, loot businesses, but instead the homes & belongings of Black people or other people of color.

In Defense of Looting goes on to examine labor movements and their recourse to militancy and looting, again focusing mostly on the post-Civil War period in the US. Osterweil traces the roots of worker rebellions in the form of “bread riots” to more sustained strikes carried out by large numbers of workers, beginning in the late 1870s.

One of the first responses to the Stock Market crash of 1929, according to the author, was widespread looting across the country. Perhaps the most instructive part of this chapter, which Osterweil seeks to emphasize, is the counter-revolutionary role of official “leaders” & union bureaucracy in denouncing and undermining worker’s militancy, including the practice of looting.

Osterweil also deconstructs the myth of “non-violent” movements during the US Civil Rights struggles of the 1950s & 1960s. This is followed up with a look at armed self-defense measures employed during that same period.

The chapter “Civil Riots” looks at the widespread use of rioting during the 1960s in predominantly Black communities and most often in response to police murder and brutality. From these insurrections, new movements arose & were strengthened, including the Black liberation movement.

“Out of the Flames of Ferguson” is the title of the last chapter in the book. It involves a brief look at the current situation in the US and the potential for revolutionary struggle against capitalism and white supremacy, which Osterweil sees as so intertwined that any resistance that does not confront white supremacy is doomed to failure:

But as we enter a new period of heightened struggle, we must learn the vital lessons of our history… There is quite simply no freedom without an end to white supremacy and settler colonialism, without the victory of Black & Indigenous liberation.

If you came to this book for the looting, you will leave with much more than a series of slogans. In Defense of Looting is an easy read; Osterweil’s informal writing style comes across as being informed by participation in the struggles she writes about. That said, the book is well researched, drawing from academic sources, radical and corporate news, as well as legislation.

In Defense of Looting: A Riotous History of Uncivil Action is in fact a comprehensive look at the history of the United States and the persistent role that white supremacy has played in shaping US society, as well as the ongoing strength of Black resistance. Considering the recent uprisings across the US and the growing political instability in that country, In Defense of Looting is at once timely and important.

Author Bio:

Gord Hill is a graphic artist & writer, author of The 500 Years of Resistance Comic Book and The Antifa Comic Book. From the Kwakwaka’wakw nation, he currently resides in British Columbia, Canada.