At the most recent protest against austerity in Quito, Ecuador, banners were raised high. A few women waved signs reading “racism is capitalism,” in solidarity with protests following the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis on May 25th.

One of them was Amparo Macas, who belongs to a local feminist group. For Macas, recent protests in the US in the wake of George Floyd’s killing relate to systemic problems in her own country and beyond to all parts of the world.

“We are in this fight together. This is a fight to overthrow the system in Ecuador, South America, and the whole world,” said Macas. “Our solidarity is with Black people in the USA.”

The June 8th protest was organized by different labor unions, including the United Workers’ Front (FUT). Protesters marched to the Santo Domingo church without any noticeable clashes with police despite the addition of new barricades wrapped with many layers of barbed wire. Throughout the march, demonstrators socially distanced by at least six feet.

The protests come as coronavirus continues to ravage Ecuador, sickening many, and leaving stark unemployment –especially in rural Indigenous communities in the provinces– in its wake. With no formal income, day laborers from local communities often travel to regional hubs to sell traditional street food.

“In my community, the majority of work is in construction or carpentry, and the women go to Ibarra to sell mote (a typical highland snack of boiled corn and pork), so this really affects people who work day to day,” said an unemployed healthcare worker from an Indigenous community. “If you don’t work, you don’t eat this week.”

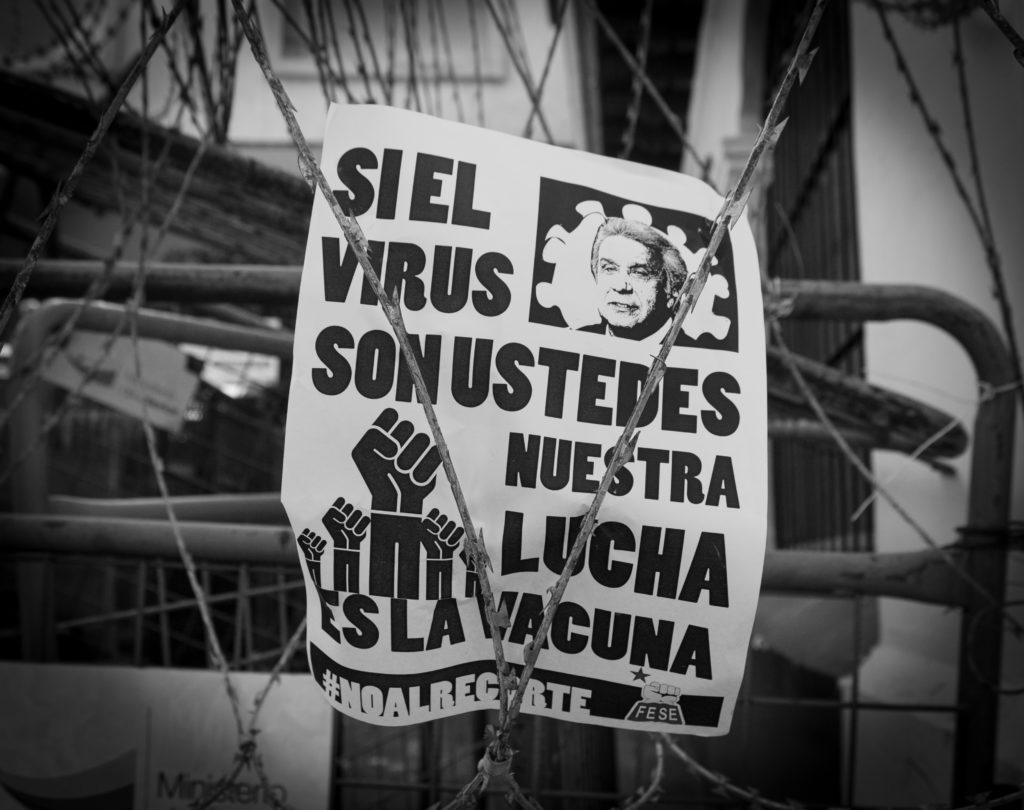

The June 8th demonstration was the latest in over six weeks of protest driven by discontent with president Lenín Moreno’s neoliberal agenda, which has only deepened in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

Since early May, demonstrations have occurred in each of Ecuador’s 24 provinces, often taking place in the early hours of the morning, before the 2pm curfew kicks in. Marchers follow health precautions to avoid large clusters of people risking infection.

“The government is applying a shock policy, we are shut in,” said Juan Borja, executive secretary for the FEPUPE teacher’s federation, during the May 28 student protest in Quito. “We are in quarantine and the government is taking advantage by using a health crisis to promote what had been proposed in October.”

Ecuador was one of many countries rocked by intense demonstrations in 2019. After Moreno’s October announcement that his government would cut decades old fuel subsidies to appease an IMF loan package, Indigenous groups, led primarily by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), arrived in Quito, leading to a tense two week standoff against police.

Moreno eventually ceded to protesters, suspending his plan to remove the subsidies. But his inner-circle of trusted ministers responsible for orchestrating the carnage remained intact.

This latest round of protests kicked off on May 4th as students responded to the announcement of the Finance Minister’s proposal to cut nearly $100 million from 32 different universities and public schools.

The students began their marches at La Universidad Central on Quito’s central western side on America Avenue and marched down Patria Avenue to El Ejido park, the same place where much of October’s 11-day strike against austerity had unfolded.

The following week, students returned to the Central University and gathered on the outskirts of the campus and chanted while drummers struck their instruments, all while socially distancing. “Moreno, escucha, el pueblo está en la lucha!” “Listen Moreno: the people are in the struggle,” they chanted. As thousands watched on Facebook live, the students marched with no interference from the police.

In mid-May, the Constitutional Court ordered precautionary measures, putting a hold on the proposed budgetary change after several education unions filed lawsuits. A judge announced hearings would be held on the massive cuts on May 28th.

A small group of protesters ensured their voices were heard the day the judges convened. As the judges gathered inside, a group of around 50 students and university union leaders were outside the Constitutional Court in downtown Quito.

According to Borja, the cuts violate the Ecuadorian Constitution. “We will have to continue fighting by way of legal and social actions in the streets: that is our path ahead,” he said.

A student protester who went by Sadjet said the protests are a “natural reaction that’s been building up for the past three years.” This is not the first time Moreno’s administration has looked to slash education funding. In previous years, proposed cuts ranged from $80 to $100 million.

The context today is further complicated by new public finance and humanitarian laws to restructure an economy hit hard by the international pandemic that were passed on May 16.

Many are skeptical about how the new laws will affect labor, the autonomy of Ecuador’s social security institute, and the budgeting powers given to the finance ministry’s head, Richard Martínez. In a statement, CONAIE called the laws “a disastrous blow to the working class.”

“It makes labor more flexible; it opens a path to firing workers in the private sector, the same is happening at the public level,” said Borja, wearing a blue collared shirt with a face mask and a shield over his face. He stepped aside from other leaders as we spoke.

“Private and public [sector] workers are without work, and possibly unable to bring food to their homes and families,” he said.

In a short address to the nation on May 19, Moreno indicated that 150,000 Ecuadorians are now unemployed. The true number is most likely far higher, as informal street vendors and market sellers have been most affected by the stay-at-home orders, but are not counted in official figures.

A December 2019 study by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses found that 1.4 million Ecuadorians were categorized as “underemployed,” as they earn less than the minimum salary ($400) or don’t work a daily minimum number of hours. Often they are looking for work, but are selling products informally to get by.

The protests were peaceful and the energy was high on May 18th, after the pandemic response laws were passed. A few hundred marched on foot and rode bicycles from the social security institute to Quito’s old town before the afternoon curfew. “Fuera Moreno fuera” “Resign Moreno” was a key chant. Once the group reached the steps of the National Bank, protest leaders spoke out against government austerity measures.

“We are going to make demands in the Constitutional Courts throughout the country, and also internationally, but to achieve that, the country must be united, we as a country must be united at all levels,” one man told a news crew in front of the bank.

The following morning in a short address to the nation, Moreno announced the closure and the privatization of a number of public institutions and embassies, including the national railway agency and the post office. He also said the national airline, Tame, would be liquidated after losing $400 million over the last five years. “Our future depends on what we decide to do now,” he said as he ended the speech.

On Monday May 25, Quito residents rallied once again, this time in larger numbers.

Students, workers, teachers, and public health professionals marched, with face masks in full use and some wearing goggles to protect their eyes. Sadjet recalled that it was “a gathering of many different sectors that can no longer, or no longer want to continue allowing the government to reduce the standard of living.”

One postal worker interviewed for this story said he had not received his salary for two months, since Ecuador entered quarantine. “They claim the business isn’t sustainable, and for that reason they want to privatize it,” he said.

The police presence was noticeable. The sun was strong, but it didn’t stop a few thousand from marching. Students began in front of their university, as they had done in the weeks prior. They marched to the same park, meeting a large number of workers already in the vicinity of El Ejido park. They continued down Quito’s narrow streets, staying a couple of meters apart.

The police had already blocked the side streets leading to the plaza where the presidential palace sits. Some protestors lit tires, and scuffles erupted between police and protesters. Eventually the police broke the barricade and split the march in half.

Later, the police dispersed crowds by chasing them on motorbikes. As demonstrators retreated to the Santo Domingo church plaza in Quito’s historic center, the police became more aggressive. People began to panic, now at closer distances than before. There were reports of tear gas being used. Many of the same repressive tactics from October were at play.

As the pandemic continues to take its toll on the nation, Ecuadorians are left with few options. “We as a country have two paths: die from hunger being locked up at home or take to the streets fighting in defense of our rights,” said Borja.

The symbolism of October’s most recent Indigenous uprising is fresh in the minds of Ecuadorians, and a reminder of uprisings past. “There is an outrage that can no longer be contained,” said Sadjet. “If we were not in a pandemic, and if we soon overcome it, we’re going to have one, two even three Octobers.”

Author Bio:

Vincent Ricci is a freelance journalist and photographer based out of Ecuador. He covers human and Indigenous rights, social movements, immigration, and politics. Follow him on Twitter @vincent__cr.