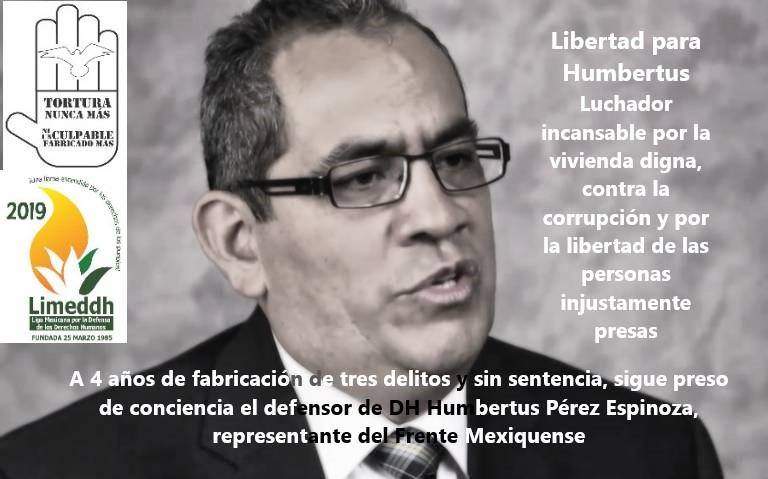

Four years after his arrest, José Humbertus Pérez Espinoza remains imprisoned in Mexico State, about a half hour outside the limits of Mexico City. The 53-year-old economist spends his days reading and writing, studying penal codes and finishing on a book he started during his imprisonment. Since he’s been inside, his health has deteriorated. He hasn’t yet been sentenced, and activists continue to advocate for his release.

Like many prisoners in Mexico, Pérez Espinoza considers himself a prisoner of conscience, and he suspects that Mexican elites want to keep him imprisoned.

The week before the fourth anniversary of his arrest, Pérez Espinoza called me from the La Perla penitentiary, from which he continues to fight to be released. He came into the public eye as the leader of the Frente Mexiquense por una Vivienda Digna, a homeowner activist movement that uncovered networks of corruption among Mexico’s public housing agency and private businesses.

Pérez Espinoza became an activist when he discovered that the development where he’d bought a home lacked adequate infrastructure to supply water to the new residents. An economist by trade with a graduate degree in history, he’d spent part of his career working for a senator. He applied his expertise in reviewing technical documents related to the housing issues he saw unfolding around him.

What Pérez Espinoza found was that over 10 million government-issued mortgages had been overvalued by up to 40 percent. His research led him to accuse public officials at the municipal, state and federal levels of participating in the housing racket. By the time of his arrest, he was the most visible, outspoken leader of a movement for homeowner rights and against government corruption.

Regardless of government promises to release political prisoners, Pérez Espinosa has languished behind bars well into the first year of Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s presidency. López Obrador, who is popularly known as AMLO, took office on December 1, 2018, after a successful campaign in which he pledged to end corruption and violence and provide amnesty for low level drug offenders and political prisoners.

There are estimated to be hundreds of political prisoners in Mexico, including environmental defenders, Indigenous activists and women imprisoned for abortion, among others. Many are activists imprisoned for false charges after threatening local political or economic interests.

Pérez Espinoza’s imprisonment is one of those many cases. In 2015, as he left a press conference, he was arrested on charges of robbing his neighbours at gunpoint. After the charges were struck down for lack of evidence, another charge of robbery was made against him. That charge was also struck down, and as he was about to be freed, in early 2016, another accusation of armed robbery surfaced.

On the phone from the La Perla prison, Pérez Espinoza listed the irregularities in his case. The evidence against him hasn’t held up in court: the witnesses on whose declarations the charges were based didn’t show up for the trial.

On September 10, AMLO promised to have his Sub-Secretary for Human Rights Alejandro Encinas look into Pérez Espinoza’s case. Members of the imprisoned man’s family have met with numerous representatives from the new government, including Senator Nestora Salgado, tasked with helping release political prisoners.

“For them, I’m innocent,” said Pérez Espinoza. Beyond the speeches and fanfare of the new administration, which the president dubbed the “Fourth Transformation” (4T) in reference to the dramatic structural changes he’s promised, Pérez Espinoza points to political motivations behind his continued imprisonment.

“The groups that defrauded us the most are in the circle of the 4T,” Pérez Espinoza said. “Since they found out I was on the list of prisoners, they started to pressure for me to not be released.” Several of the businesspeople involved in the housing fraud Pérez Espinoza uncovered are close members of López Obrador’s advisory circle.

Among them is Monterrey businessman Alfonso Romo Garza, López Obrador’s chief of staff, who was CEO of the insurance company Seguros Comercial América, now Seguros ING, which insured some of the overvalued houses in the mortgage scheme. Romo’s appointment as the president’s chief of staff was an early sign of the new administration’s attempts to cozy up to Mexico’s business elite, long opposed to AMLO.

Pérez Espinoza says that when members of López Obrador’s government ask him who is it that’s against his release, he tells them the following: “Talk with Alfonso Romo.”

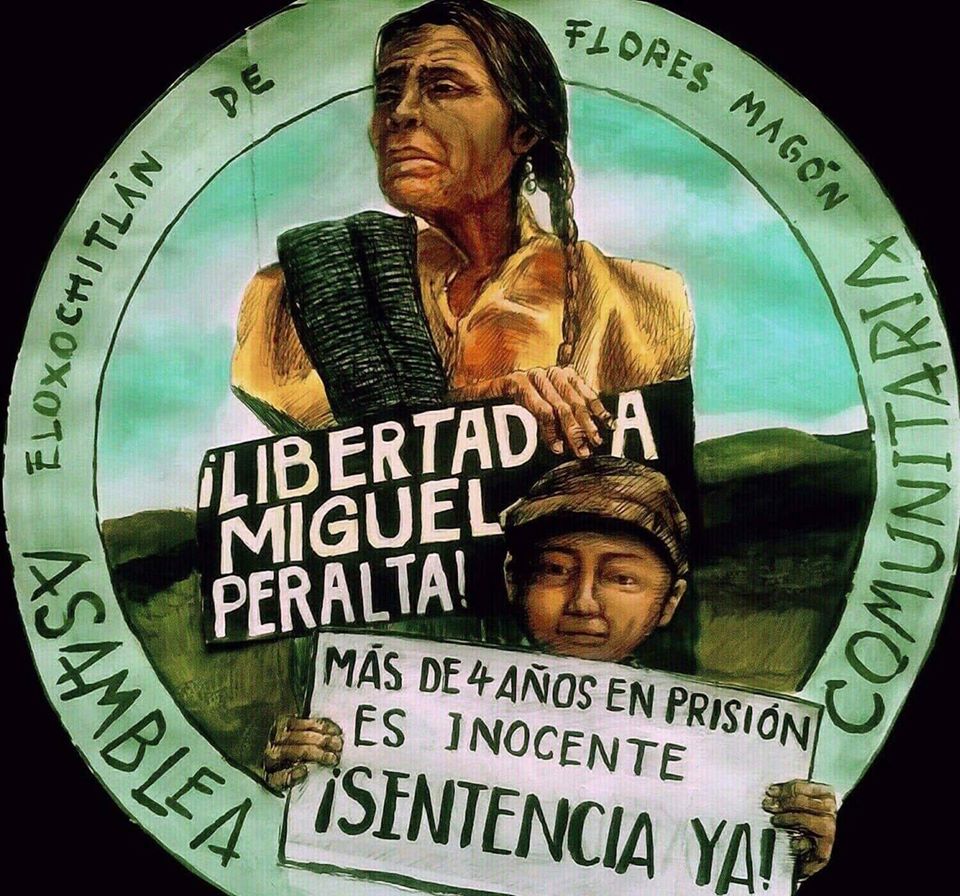

Just weeks before I spoke with Pérez Espinoza, another political prisoner, Indigenous activist and anthropologist Miguel Angel Peralta Betanzos was released from prison in Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca, after serving four and a half years.

The day before Peralta’s release, in the midst of a grassroots campaign demanding his freedom, his lawyer Roberto López Miguel expressed his exasperation with the judge’s stalling. “We know the sentence has to be that he’s innocent,” López Miguel said in an interview in his Mexico City office. “All they can do now is delay the process.” Peralta’s file initially included seven other prisoners from Eloxochitlán who were freed because the evidence against them was inadequate. “They’re delaying it,” said López Miguel, “but they can’t impede his freedom.”

Late into the night on October 14th, a judge found Peralta innocent on charges of murder, for which he’d been previously sentenced for 50 years. But his release, while welcome, leaves much to be desired.

“We still have comrades with arrest warrants who are displaced without legal certainty about their status,” he said over the phone from Oaxaca days after his release. Peralta was one of eight prisoners from Eloxochitlán imprisoned under homicide charges, the seven others still haven’t been released. “At the end of the day, there hasn’t been a single piece of evidence to sentence us,” he says. “We haven’t been asking for a whim, just that justice be done.” Peralta had been imprisoned, along with seven others, in the context of an ongoing political struggle between autonomous forms of self-governance and political party rule.

The Zepeda family represented the latter in Eloxochitlán de Flores Magón, Peralta’s home town in the state of Oaxaca. Manuel Zepeda Cortes was mayor of the town from 2011 to 2013. As reported by Mexican journalist Laura Castellanos, in November of 2014, a group of armed men, which members of the Asamblea Comunitaria believe acted on Zepeda’s behalf, took over City Hall and shot at members of the Asamblea Comunitaria. Zepeda’s own son, as well as a bodyguard, were killed in the resulting confrontation.

Peralta wasn’t even in Eloxochitlán at the time of the incident. Several months later, in April 2015, a group of police dressed as civilians arrested Peralta in Mexico City and turned him over to Oaxaca’s state police, who took him from Mexico City to Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca. In September 2018, Peralta was sentenced to 50 years in prison. His trial was replete with irregularities. In addition to falsified declarations, and key witnesses’ failure to appear, the authorities failed to bring Peralta to the hearings. Peralta was granted a retrial, scheduled for September of 2019.

While Peralta awaited his second trial from prison, members of López Obrador’s government re-avowed their commitment to ending the influence of political interests in the judicial process, and releasing political prisoners. If taken seriously, that task would severely undermine the power of Mexico’s political and economic elite, including close members of the president’s own circles.

Despite the overwhelming evidence in Peralta’s favor, his sentencing had uncomfortable political implications for the 4T: Elisa Zepeda, whose brother Peralta was charged with killing, is now a representative for Morena, the ruling party. Peralta’s final hearing took place on September 19, 2019, after which he went on a hunger strike until the judge gave his sentence.

The judge was entitled to 15 days to give a sentence, plus, if the case file is longer than 200 pages, one day for every 50 additional pages. Peralta’s file was over 6000 pages. Legally, sentencing could have taken months. Peralta’s hunger strike lasted 26 days. He was released, skinny and starved, in the middle of October.

In the months after his election, López Obrador commissioned senator-elect Nestora Salgado, a former political prisoner herself, to compile a list of political prisoners who may be eligible for amnesty.

As of last November, Salgado had a preliminary list of around 500 prisoners; in December, after López Obrador’s inauguration, she turned over a shorter list of prisoners whose cases should be examined. The list that Salgado turned over consisted of 199 cases in 18 states, including 180 men and 19 women. The Secretary of the Interior (SEGOB) then took on the task of evaluating the list, under the direction of Subsecretary Encinas.

The government has released little information about the process. Only 25 of the names on Salgado’s list were made public. Earlier this year, Encinas stated that 538 cases of political prisoners currently were under evaluation and 31 had been released.

Ensuring justice for political prisoners in Mexico poses a monumental logistical challenge. Many are imprisoned under false charges for fabricated crimes, even just figuring out who is a political prisoner implies extensive, detailed fieldwork.

Once identified, the process of evaluating the cases can be slow and replete with political obstacles. Mexico’s judicial system is notoriously corrupt, and, as in the cases of Pérez Espinoza and Peralta Betanzos, some of those behind the imprisonment of political prisoners are fixtures in the current government.

In order to examine cases of prisoners that may be eligible for amnesty, SEGOB created an internal organism, the Unit of Support to the Judicial System. Paulina Tellez, the head of the Unit, declined to comment on specific cases of political prisoners, but said that the commission takes a uniform approach to all the cases they receive.

“We don’t look at them as political prisoners,” Tellez said. “We look for where irregularities exist, where there has been fabrication of evidence or irregularities by judges. We respect the autonomy of all the authorities involved, but our job is to point out errors.” Since the unit was created in mid-June, Tellez says, they have been notified of between 1,400 and 1,500 cases, in the form of a request from activists or independent organizations or a handwritten letter from someone in prison. She says that the unit attends all requests that it receives.

Among those cases was that of Miguel Peralta. When Peralta’s family heard that Salgado was making a census of political prisoners, they decided to contact her with the information about Peralta’s case. Tellez says that the Unit had contacted the judge in Peralt’s case to point out the irregularities in his file, resulting in his release.

López Miguel, Peralta’s lawyer, is dubious about the integrity of SEGOB’s efforts. “If they did anything, it was to intervene so that the ruling would be given shortly and with basis in the legal precedents, and given the precedents, it would have to be a resolution of freedom,” López Miguel says. “All the work was already done.”

In addition to the work of SEGOB, in September, López Obrador sent a law to Congress that would give amnesty to people imprisoned for minor offenses, including robbery, minor drug crimes and charges related to abortion. Unfortunately, even if it is passed, the law isn’t likely to benefit all that many incarcerated people.

Among Mexico’s political prisoners are an unknown number of women are imprisoned for charges related to abortion, generally at the municipal or state level. Verónica Cruz Sánchez, the director of the Guanajuato-based abortion rights organization Las Libres, explains that freeing women imprisoned for abortion is not as easy as passing a blanket amnesty and handing over the keys to the prison cells.

No one knows quite how many people have been imprisoned for abortion in Mexico. Las Libres has indexed over 200 cases of women in prison for abortion, but counting those cases requires extensive prison visits. Though a woman may be imprisoned for attempting an abortion, the crimes on the books are usually related to homicide or infanticide.

“Some of these women don’t even know why they’re in prison,” said Cruz Sánchez. “They may not know how to read, or they may be Indigenous and not speak Spanish.” Given the amnesty law, she says, political conditions are favorable for the work required to free those women.

In September, the state of Oaxaca became the second state, after Mexico City, to decriminalize abortion. Cruz Sánchez says that the victory has inspired a new wave of local initiatives to address abortion rights across Mexico. Las Libres is currently consulting with authorities in Michoacán and Guerrero towards carrying out the prison visits needed to kick off a process that would see prisoners for abortion released.

Lawyer López Miguel doesn’t think an amnesty law would go very far in ensuring political prisoners are released. A regular feature of the fabrication of crimes against political prisoners, he notes, is the accusation of serious crimes, such as homicide and kidnapping. An amnesty law wouldn’t resolve their cases, rather, each individual case would have to be re-litigated. Additionally, as in the cases of Peralta and Pérez Espinoza, many political prisoners are charged on the state level, not the federal level, so a federal-level amnesty law would apply to a fairly limited population.

In the context of continued repression of activism and dissent in Mexico, some see the government’s pro-political prisoner discourse as a farce. Earlier this summer, police arrested two migration activists, Irineo Mujica and Cristóbal Sánchez, under fabricated charges of human smuggling.

The charges were later dismissed for lack of evidence, but the two activists’ cases remain open. Human rights defenders, land defenders and Indigenous rights activists throughout the country continue to be criminalized for their efforts, and communities opposed to state-sanctioned megaprojects continue to face the militarization of their territories.

Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum, also of Morena, promised to dissolve the city’s riot police when she assumed office in December of last year. Instead of disappearing, the force was replaced by two new police bodies, a special operations task force and a tactical aid unit.

On October 2nd, during the annual march to commemorate the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre, in which the Mexican army slaughtered an unknown number of student protestors in Tlatelolco square, riot police violently suppressed the crowd. “Even after saying that this government is different, they couldn’t resist the temptation,” López Miguel says. “Arrests keep happening.”

Gonzalo Molina shares López Miguel’s disdain of the current administration’s discourse. Molina is a commander of the CRAC-PC, an autonomous self-governance institution and community police force in the state of Guerrero. He was imprisoned for over five years on charges of kidnapping, terrorism and illegal arms possession, and was released this February after successfully defending himself against ten different charges.

Since being released, Molina has survived several kidnapping attempts, and when he comes to Mexico City, he takes precautions to avoid being followed. When I met him in the south of the city, a friend of his came to greet me as Molina paced the perimeter of the plaza where we’d agreed to meet. Molina wore a hat pulled low over his weather-worn face. He told me he feels far less safe in the city than in the remote mountain terrain where he carries a firearm. If anyone comes for him there, he knows he can defend himself.

Molina is adamant that no one but himself is responsible for his freedom. “People supposedly on the left said, ‘he should get out because of an injunction, amnesty, the prosecutor should desist,’” he says. “But I said, I’m not going to get out because of an amnesty. I’m going to get out because the laws were respected.”

Salgado, the senator that López Obrador tasked with creating the list of political prisoners, is a former member of the CRAC-PC who was arrested in 2013 under charges of kidnapping and organized crime.

Molina considers Salgado’s participation in the political establishment to be a betrayal. When I asked him about Salgado’s initiative, his face twisted into an expression of disgust. “They told me I was on the list, and I asked for them to take me off of the list,” Molina says, referring to Salgado’s census of political prisoners. “She got out because she negotiated. My freedom will not be negotiated.”

He continues his community activism in the Montaña region of Guerrero, but whenever he comes to Mexico City, he takes stringent security precautions. He is enrolled in the state Mechanism for Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, but he finds it useless.

For Molina, the Mexican state continues to function as it always has. “Either they kill us or disappear us or imprison us,” Gonzalo Molina says. “As social activists, if all goes well, they just imprison us.”

Author bio

Madeleine Wattenbarger is a journalist in Mexico City, where she writes about human rights, migration, gender and urbanism. Follow her on Twitter at @madeleinewhat.