This story was first published by Global Voices and is shared here under a Creative Commons license. Read the original here.

At first glance, no two words may seem as far removed as protest and embroidery. But in Belarus, where the opposition is disputing Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s hold on power after the August 9 presidential election, the revolution is not being just broadcast over social media — it’s being embroidered.

The official results of these presidential elections, announced on August 10, gave Lukashenka over 80 percent of the vote, while the leader of the recomposed opposition Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya gained less than 10 percent. Those results have not been accepted by Tsikhanouskaya, who decries mass electoral fraud, citing independent monitoring by activists, and demands official talks with Lukashenka.

But for the government in Minsk, the elections are a done deal, and no further discussion is forthcoming. Furthermore, internet access has been cut off throughout the country since late August 9. This means that most Belarusians have great difficulty finding out about ongoing protests across the country, in which the police have used violence against protesters. Over 5,000 have been arrested and one death has been reported.

Since Lukashenka came to power in 1994, this eastern European country of nearly 10 million has never held a free and fair election. Although these protests are the largest in recent years, previous elections in Belarus have prompted similar responses, followed by crackdowns and mass arrests. Historical memory of any trace of protest is thus erased from the public consciousness.

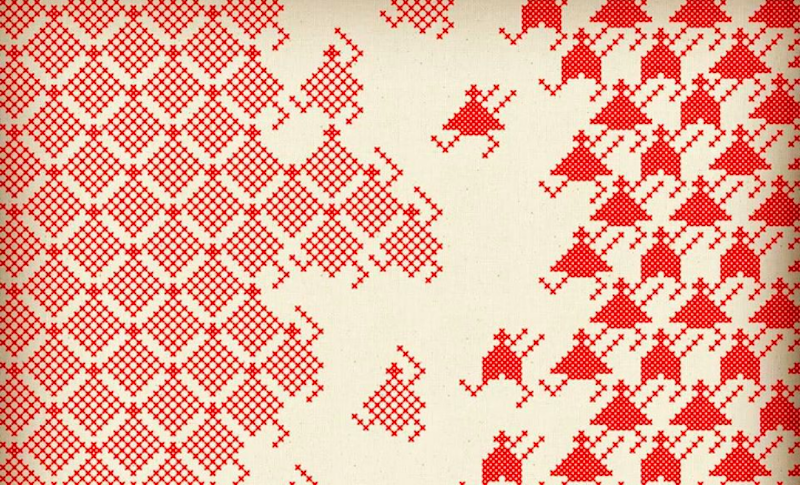

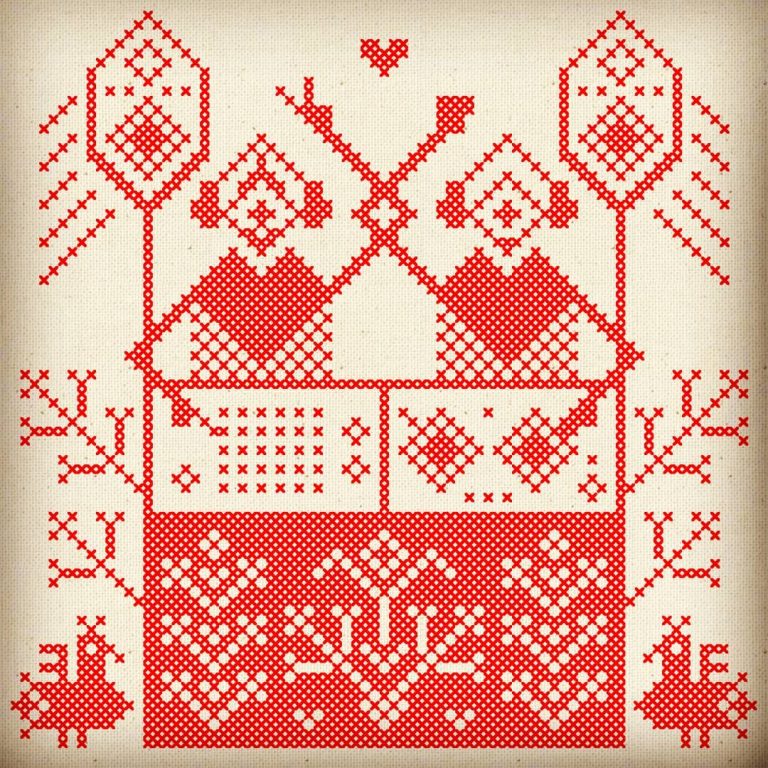

That’s why one Belarusian artist has decided to immortalize the protests of August 2020 through embroidery. Rufina Bazlova, who lives in Prague and has studied art in the Czech Republic, has chosen an idiom close to the hearts of many Belarusians: red embroidery on a white background. For many years after independence, this kind of embroidery was a key part of Belarusian folklore, used to promote the country in tourist adverts.

But it also has a political connotation. During Belarus’s independence after the collapse of the Russian Empire, the country used a white-red-white flag as its tricolour. It harked back to the days of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth of which Belarus was a component, but its newfound independence was short-lived: the state was reabsorbed into the Soviet Union in 1919.

So when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, it once again became the flag of independent Belarus and asserted a Belarusian identity distinct from Russia. But in 1995, Lukashenka restored the green and red flag of Soviet Belarus (albeit without the hammer and sickle), thereby making the red-white-red flag a symbol of resistance to his rule.

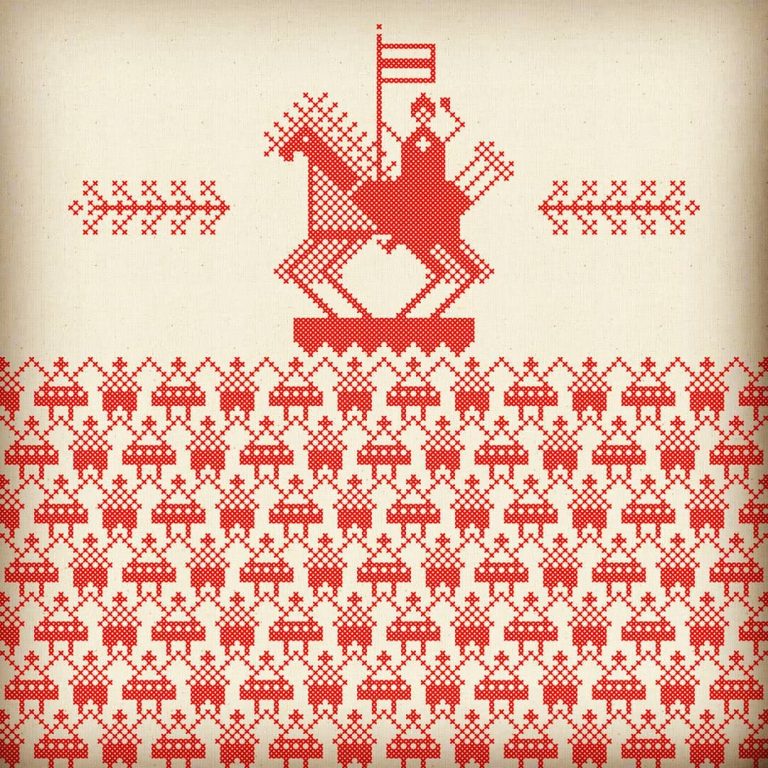

That symbolism continues to this day. It is often seen in the current protests, where it serves as a symbol of resistance to the current regime, explains Max Ščur, a Belarusian-language writer and activist who lives in Prague, the Czech capital:

What we are witnessing now in Minsk and Belarus is a democratic revolution, civic society is being born. Belarusian cultural identity is complicated, but right now it’s all about democratic values and an active anti-regime position. It’s a “civic”, not “ethnic” model of society in progress

Ales Plotka, a singer and civic activist from Belarus also based in Prague, agrees. However, he says that the status of the flag is somewhat ambiguous:

The white-red-white flag is a common symbol of resistance against this unfair government. It was associated with the traditional opposition in the past, and demonized by Lukashenko ideologists, but is now used country-wide by all sorts of people. There is no official ban on it, as it is really a historical flag, known for over seven centuries. Sometimes people carrying it are attacked, usually by the police. During events celebrating the anniversary of the independent Belarusan Democratic Republic [1918-1919], it was widely used, and people leaving the area were temporarily arrested for carrying it. But today, the more it is used and recognized, the less often people carrying it are attacked.

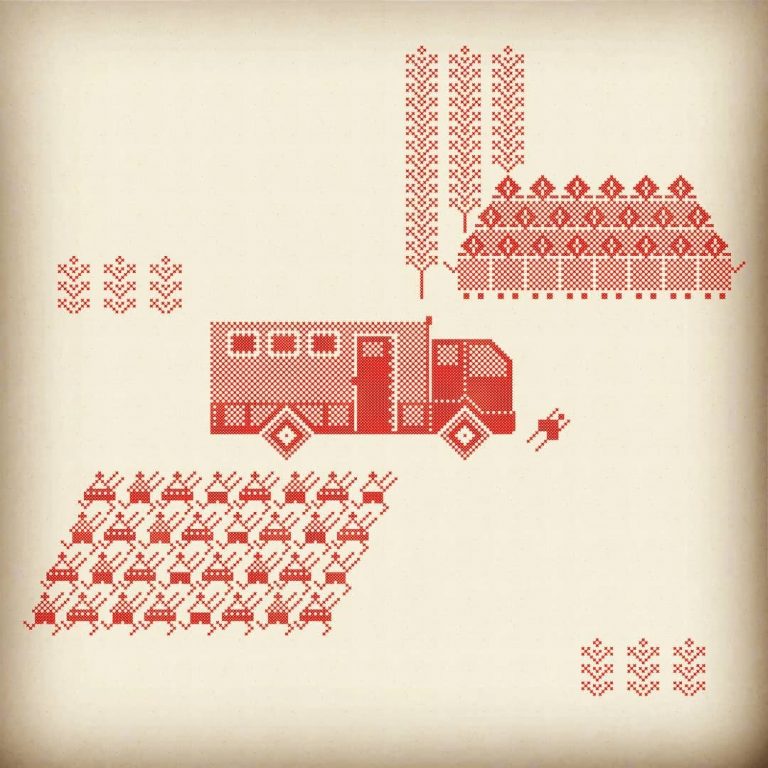

Therefore Bazlova’s work has a potent political symbolism. This can be seen in her choice of events to embroider, such as the case of two DJs who hacked a pro-Lukashenka event by suddenly playing a song by the late Soviet rock musician Viktor Tsoi about the need for change, which has become something of a protest anthem used by the opposition to rally people against Lukashenka.

Bazlova, who is Belarusian but has lived in the Czech Republic since 2008, told GlobalVoices what motivates her work:

She also explains how she combines comics and embroidery into one form of expressive art: