Sadness, pain, and unease have overtaken Bolivia in the past weeks. Thirty-four people have been killed, the injured number over eight hundred, and dozens have been imprisoned. Hate speech proliferates, confrontations are common and distrust is rife. There is generalized confusion, caused by a conflict in which there is no end in sight.

Bolivia has moved from having a party that appealed to fraud as a means of staying in power, to a polarized political scenario in which violence, fear, and death became mechanisms for the control of the state apparatus. That is the summary of the painful trajectory of Bolivian politics over the last month. This is not a story of victims and saviors, but rather a fight over power, in which key actors had no qualms about trampling on the life and dignity of the Bolivian people.

The government of Evo Morales committed fraud, after violating regulations and manipulating the Constitution in their favor. This–together with an accumulation of ecocidal, extractivist, and anti-communitarian aggressions over the last 14 years–cannot be disregarded, minimized, or pushed into the background if the future of the Bolivian political process is to be understood. The electoral fraud was the crown atop an accumulation of aggressions, and it also became a trigger for the deep political crisis we are now living.

It is well established that those who stood in the way of Morales’ re-election were silenced, as was Indigenous Constitutional Magistrate Gualberto Cusi, who was removed from the bench after opposing a second term in 2014. In a painful breach of privacy, the Minister of Health later revealed Cusi had HIV, for which he was publicly ridiculed. There’s also the case of the criminalization of the magistrates who stood against Morales’ second re-election. And the case of the judge in Santa Cruz who was persecuted and harassed for insisting on its unconstitutionality.

In 2016, the MAS lost a referendum that had been called to constitutionally allow Morales to stand for another reelection (the constitution only permits one consecutive reelection). But the Constitutional Court, which is influenced by the ruling party, did not recognize the results of the referendum. Rather, there was an “appeal for abstract unconstitutionality” that determined that indefinite reelection be considered a “human right.” This led to the most recent October 20, 2019 elections, which were manipulated to avoid a runoff. It was one of the most grotesque frauds in the country’s recent history.

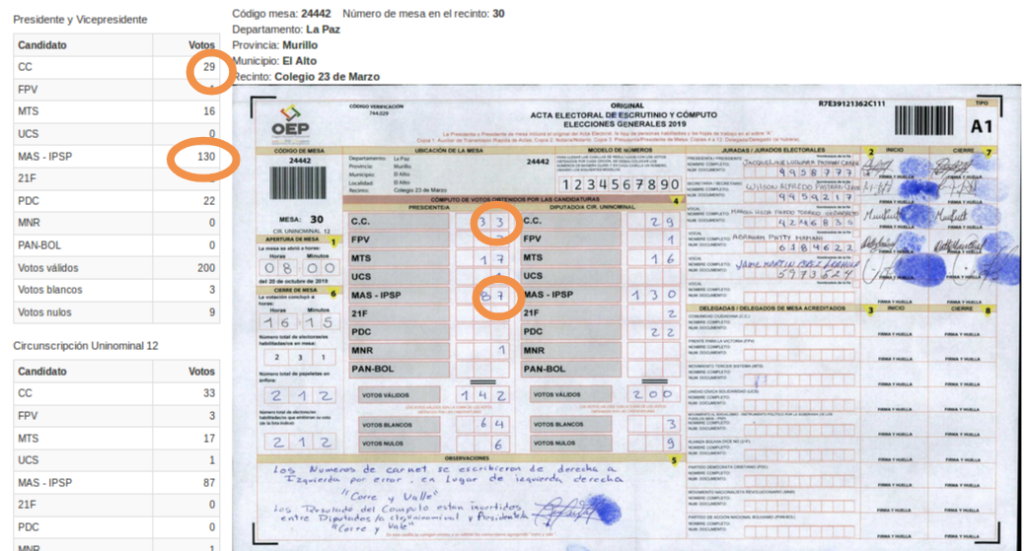

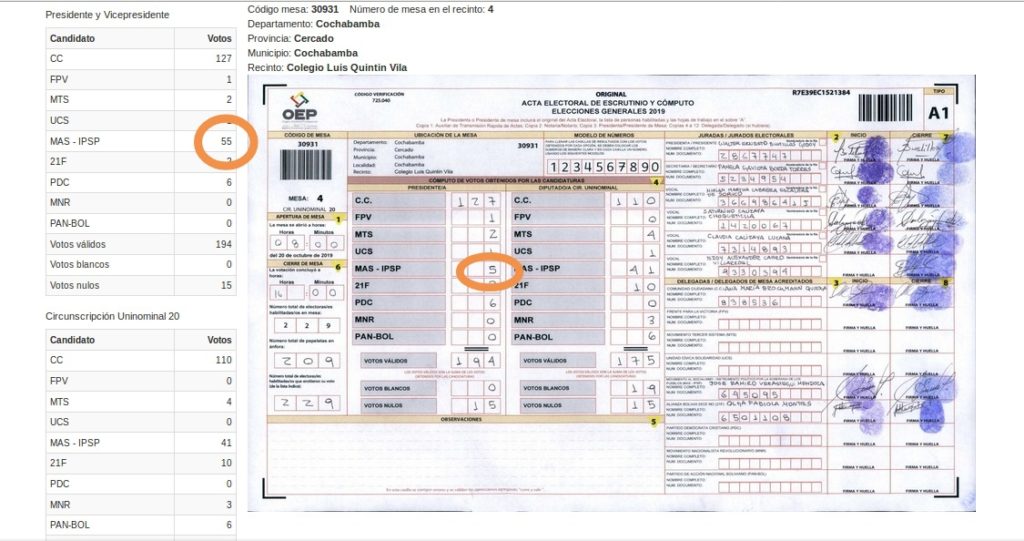

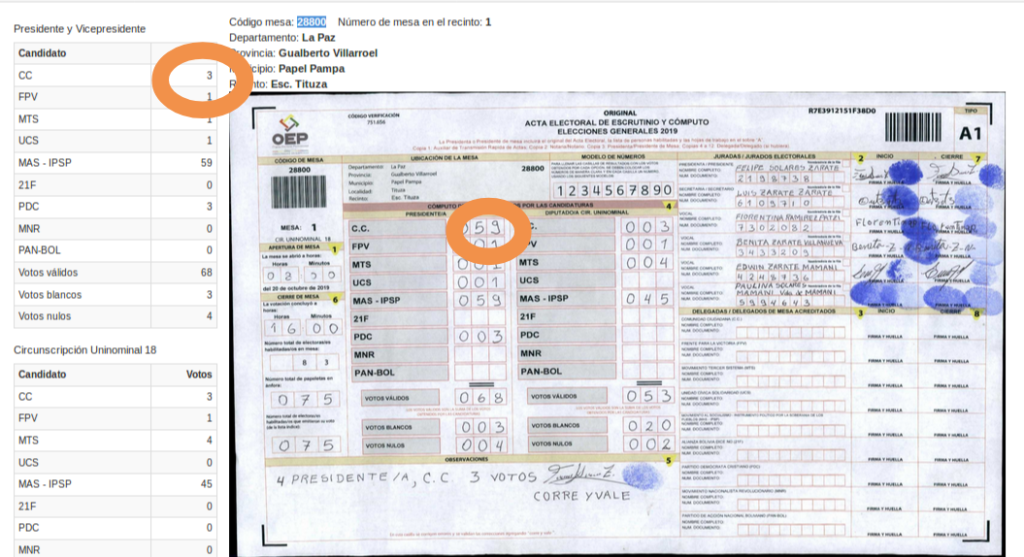

The fraud was ridiculously evident. Even before the election, people who were once close to the MAS had already warned about it. The evidence for the fraud is overwhelming and goes well beyond the preliminary report of the Organization of American States (OAS). Separate reports have been prepared by academics in Bolivia (released November 6) and in the United States (released November 25). Tallies of ballots were digitized “backwards” or erroneously so that they benefited the ruling party, votes were cast by nonexistent or dead people, and there were irregularities in the transportation of electoral material.

In Bolivia, the people knew all of this and that’s why there were 20 days of blockages that paralyzed the country before the OAS confirmed the fraud and Morales resigned. All along, the government cynically denied it.

After the elections, the MAS turned to the OAS to ask for an audit of the elections, which opposition candidate Carlos Mesa finally rejected, as OAS Executive Secretary Luis Almargro had explicitly supported Evo Morales (even traveling to the Chapare to see him). It appeared that the OAS was more part of the government than a neutral judge, even so the OAS asserted that the October 20 elections could not be validated. In other words: yes there was fraud. It was not the OAS that spoke about fraud for the first time, rather the fraud was so massive that even a government appointed judge could not deny it.

Between October 21 and November 10, the slogans in the streets went from “we want a second round” to “we want new elections.” But things changed after the release of the preliminary OAS report, which the government had promised to respect.

Hours after the OAS report was issued, Morales said they would call for new elections. He did so without talking about fraud or who was responsible for it, or detailing conditions for the new elections. Would the new Supreme Electoral Tribunal be elected by those who had directed the fraud? Would Evo Morales run for election again, ignoring the Constitutional Referendum of February 21, 2016? It seemed that the government was seeking a clean slate for new elections, without ever addressing the outrage of the Bolivian people.

In a climate of tension and violence, a police mutiny began in Cochabamba, Sucre, Santa Cruz and Oruro, eventually spreading to La Paz. We don’t know if the police mutinied as part of an advance strategy from the right, or whether it was part of a victimization strategy by the MAS to justify a climate of violence. There are precedents for the latter: academic Boris Nehe proposes we interpret the 2008 El Porvenir Massacre in the department of Pando in this light. Something similar took place on January 11, 2007, when social organizations were protesting against the governor of Cochabamba for his adoption of the autonomist demands of the Media Luna region, which led to a confrontation between in which four people were killed, three campesinos and one city resident.

The November 2019 police mutinies were followed by an armed ambush carried out by MAS affiliated sectors against miners that were traveling from Potosí to La Paz to protest the fraud.

It was in this context that various emblematic organizations from the popular sectors began to call for Morales’ resignation. Among them were the Public University of El Alto (UPEA), the Federation of Mine Workers’ Unions of Bolivia (FSTMB), and the Bolivian Workers’ Confederation (COB), the largest union in the country. A day after these organizations demanded Morales resign did the CAINCO, which represents oligarchic power in eastern Bolivia, and had been an ally of the MAS in recent years, follow.

Following widespread abandonment by organizations and institutions, dozens of MAS authorities, deputies, senators, governors, mayors, and so on also resigned, some in protest and others out of fear. Although the Pro-Santa Cruz Committee – the political body of the rancid right of eastern Bolivia– had previously asked Morales to resign, it was not until November 10th that their slogan became widespread.

For this reason, in Bolivia, when the military commander Williams Kaliman, an ally of the MAS, a self identified “soldier of the process of change” and anti-colonialist “suggested” Morales resign, it almost sounded like a decision had already been made by those in power. The Army commander spoke in a climate of growing social conflict, in which several people had already been killed. The Armed Forces were the last to request Morales’s resignation, which is why politically the idea of a coup d’etat made no sense in Bolivia at that time: following rigged elections, and faced with the arrogance of fraudulent rulers, millions of Bolivians had already demanded the president’s resignation.

Without counting the multiple aggressions by the MAS government that various sectors of Bolivian society have been enduring in recent years, especially those related to ecocidal, extractive, and anti-communitarian policies, what happened next cannot be properly named: the people were aggrieved by a government that, violating the entire constitutional order, wanted to steal the elections.

Following the October 20 elections, the way in which the Morales government decided to deal with the accusations of fraud was through polarization and social confrontation. The government unleashed a climate of violence and confrontation with the most rancid rightwing organizations in Bolivian politics.

Luis Fernando Camacho, leader of the Pro-Santa Cruz Committee, demonstrates this. Before the elections we knew that said committee existed, but in reality, its leaders’ names were not widely known outside of Santa Cruz. It was following the elections that hate speech escalated, creating a polarization that was functional for both “sides.”

The right does not play games, and it rapidly seized on the opportunity, capitalizing on and monopolizing a great deal of discontent towards Morales and electoral fraud. Eager for power and from a racist, conservative and fundamentalist discourse, it gained ground and directed protest demands in the first weeks of the conflict, even surpassing on several occasions right-wing “moderate” Mesa, who, being the candidate who would go to the second round, had been directly affected by the manipulation of the elections.

This conservative right is articulated around local civic committees, conservative legislators, evangelist churches, and the largest economic interests in the country, which always play on all sides. It also undoubtedly has the support of the CIA and other international organizations involved in building authority on behalf of the world’s most powerful corporations. In fact, this right is very similar to the neoliberal right in Bolivia at the beginning of the century. It was they who gained momentum following the elections.

What happened between the resignation of Morales and when Jeanine Añez assumed the presidency (the country was two days without a government) is something that is not clearly intelligible at this time. High ranking politicians supported the use of terror in order to generate uncertainty in a calculation for power.

The fear experienced by residents of La Paz, El Alto, and Cochabamba on the night of Morales’ resignation was unprecedented and horrific, but also clearly planned. It was violence unleashed by the outgoing government as punishment, and a mechanism of blackmail so that the people would call for the return of Morales. This violence, in turn, was connected with the repressive and violent response of the public forces when Añez assumed the presidency.

In this crisis, politics has been stripped of a legal framework. In Bolivia, we are used to producing broad agreements that enable viable realities, going beyond legislation that can become obsolete in extreme situations. Between 2000 and 2005, in the midst of major popular uprisings, this happened several times, and it was what was expected after Morales’ resignation: an agreed upon constitutional succession. A broad agreement would have led to a peaceful resolution to the conflict that had been paralyzing the country for more than 20 days. But neither the MAS nor the re-articulated rancid right–the two extremes of polarization–had that intention.

While Morales played the power vacuum to generate anxiety and uncertainty, the Right bet everything on the control of the state, negotiating first with the police and the military. Thus, without a broader agreement, but with the support of the Armed Forces and under the legal figure of the abandonment of functions, which was validated by the Constitutional Court, Janine Añez assumed the presidency. She did so surrounded by nefarious people. The kinds of people who burn wiphalas, who bring the bible into the government palace, the kind who fire bullets and shoot to kill, and who promulgated Supreme Decree 4078, which exempts the military from criminal responsibility.

The Sacaba and Senkata massacres that took the lives of more than twenty people added to the deaths during those days. Many of these deaths occurred in the context of mobilizations, which occurred in part due to the pressure that MAS leadership was exerting on their supporters to show that the Bolivian people were calling for the return of Morales. None of this justifies the disproportionate use of violence or the firing of lethal weapons at protesters. There is no international treaty or humanitarian principle that could justify the Añez government’s disproportionate use of force.

It must be clear that this disproportionate violence was also exercised against social mobilizations that explicitly are not Masista, but who have taken to the streets in repudiation of violence and death and in defense of life, and their own values and symbols. The Añez government, to justify the repression, labeled these and other groups “terrorists.”

The repressive government of Añez sent the armed forces and the police to massacre the people. This cannot go unpunished, and it must be denounced.

If in Bolivia there has been one coup or many coups, they have been against the people. The people saw how their leaders violated the constitution, they saw how their vote was rendered worthless and they felt cheated, it was a coup against those who were repressed, against those who lost their homes or whose homes were looted, against those who were victims of violence related to a political calculation, against those who lost their lives.

It was not a coup against Morales or his fraudulent government, which, as Rita Segato says, “fell under its own weight.” It was the people in the streets and, as we saw, the former allies of the MAS who ended up overthrowing it. As the Yampara Nation stated: Evo Morales “has turned out to be more qhara [white-European or mestizo invader] than those with blue eyes and white skin.”

It is for this reason that in Bolivia, the slogan of coup d’etat, which was rampant internationally, generally made no sense. And that does not mean that there is no clarity on what is taking place today: in Bolivia today there is a government that has the support of congress and full constitutional legitimacy, but that is authoritarian, violent, fundamentalist, and militaristic.

However, we must consider two things. First, that the repressive Añez government does not cancel out the aggressive nature of the predecessor government. Second, that that same government led us towards this disaster. Turning a leader (caudillo) and his helper into victims, when it was they who attacked and harmed the people, and who are responsible in great measure for what is taking place in the country today, is a manner of encouraging the binary logic of polarization, which gives weight to those up above and contributes to the persistence of the violence against those down below.

The important thing is not to arrive upon a correct theoretical definition of what is happening in Bolivia. Rather it is crucial that whatever label we use recognizes that the repressive fascist-leaning government that has been killing people in recent weeks is intricately linked to the MAS, to the violence it exercised for years, to the political persecution of dissident Indigenous leaders, to the systematic dismantling of community lands and their organizations, to the corrupt and clientalist scaffolding of the state structure, to the unprecedented destruction of Bolivian wilderness, to transnational extractivist policies, to the systematic transgression of the constitutional order, and to electoral fraud.

What is important is to break the mechanism of repetition. Making Morales into a victim does just the opposite. It is important to get out of a caudillista-patriarchal episteme that idealizes the aggressor, exempts him from responsibility, and blames everything (and everyone) else for what is happening. Of course, the right also throws punches, and does so intensely, but the MAS was throwing punches first, and we cannot stop saying that. I fail to understand what is so “strategic” about being silent regarding the factors that led us to this disaster.

In the face of this repressive government, many things are happening simultaneously in Bolivia. Various social sectors are trying to reorganize their autonomous political power, but they are having a difficult time in doing so. The negligible role that organizations such as the Unified Trade Union Confederation of Peasant Workers of Bolivia (CSUTCB) or the Bolivian Worker’s Confederation (COB) have had in this conflict is striking. This seems to have to do with internal disputes and atomization resulting from the process of decomposition of the MAS, and the way in which the corporatism of the party permeates these organizations. It has been the neighborhood assemblies of El Alto that have had the most visibility following Morales’ resignation, although schisms and fatigue are also evident.

Over the last weeks, an agreement has been reached between MAS legislators and the Añez government. The agreement accepts that Morales resigned and abandoned his duties and therefore legitimizes the new president, it accepts the declaration nullifying the elections of October 20, and establishes designation of a new Supreme Electoral Tribunal to call for new elections, in which Morales will not participate, although the MAS will.

It is an agreement that by no means resolves the deep social wounds that have been opened in recent weeks, but that nonetheless expresses that a fraction of the MAS has distanced itself from its leader and is seeking to bring peace to the country, in an attempt to preserve the strength that this party still has, even at a time of deep internal decomposition and conservative onslaught.

It must be understood that the Añez government encountered a limit: a battered but still mobilized society. The intention of this government was to restore the old neo-colonial state, with blood and the use of supreme decrees, ignoring the Plurinational Assembly. The resistance, however confusing, is what forced the Añez government to seek a negotiation in parliament.

This agreement appears to have put a stop to the use of repressive violence by state forces, but it has left the country in a state of tense calm.

What remains is a repressive government that does not intend to modify the predatory and dependent economic matrix overseen by the MAS government, beyond the fact that the beneficiaries may be different. There is a rising fundamentalist and fascist Right, and an aggrieved, battered, and fragmented society with little capacity for autonomous organization, as a result of what Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui has called a “long process of degradation.”

Although new elections may mark a partial exit from this disaster (as long as the Constitution is respected), political reorganization from below will be that which will really allow us to seek out other horizons of struggle, as we have learned from our long history.

•

This is a translation of an article originally published by Zur, which was expanded and updated in collaboration with the author. Translated by Toward Freedom.

On December 2, 2019, the three electoral certificates showing erroneous vote tallies posted with this article were still available online from the official website of the October 20 elections. We accessed them by entering the five digits above the barcode on the original certificates in the “Búsqueda de mesa por código de 5 dígitos del acta” field.

Author Bio:

Huascar Salazar Lohman is a Bolivian economist whose research is focussed on community struggles.