This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Earth’s forests oxygenate the atmosphere and store vast quantities of planet-warming carbon dioxide (CO₂). But research suggests that the health of these vast ecosystems in large part depends on the work of indigenous people.

Indigenous territories and protected areas cover 52% of the Amazon forest and store 58% of its carbon. A recent study found that these areas had the lowest net loss of carbon between 2003 and 2016, with 90% of net emissions coming from outside these protected lands.

“Where indigenous people live, [in Central America] you will find the best preserved natural resources,” declared the International Union for Conservation of Nature in 2018. A study published that year found that “indigenous people are crucial for the conservation of a quarter of the land of the Earth”.

In the forest territories that indigenous people maintain deforestation is lower, more carbon is stored and less emitted, biodiversity is better conserved, and resources are more sustainably and fairly managed.

But indigenous territories and the biodiversity and carbon they protect are under siege. For indigenous people to continue in this invaluable role, they need secure land tenure and strong local governance systems. Nowhere is this currently more apparent than in Bolivia.

From championing to co-opting indigenous rights

On indigenous territories in Bolivia that have secured property rights, deforestation rates are 2.8 times lower than outside of them. Such lands cover 20% of the country’s territory, so the contribution of indigenous peoples in Bolivia to fighting climate change is substantial.

But this situation has been undermined by Bolivia’s development policies, and could be threatened further with the recent shift to a right-wing government.

In the last two decades, Bolivia has led the world in championing indigenous rights. Upon taking power in 2006, Evo Morales helped write a new national constitution. It paved the way to redistribute land to indigenous peoples and support their claims for self-government.

Morales also put indigenous peoples at the forefront of climate change discussions, when in 2010, he organised the People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth. The People’s Agreement that emerged highlighted the important role that indigenous peoples play safeguarding the planet.

But during his second term in power, the government’s commitment to indigenous rights and to the fight against climate change faltered. In 2010, Morales approved the construction of a road through an indigenous territory and protected area, which was bitterly resisted by the Mojeño people, alongside other indigenous peoples of the lowlands and highlands.

Morales announced his intention in 2013 to expand farming lands from three to 13 million hectares over ten years – allowing agriculture businesses to encroach on indigenous homelands. Morales then increased the area of land that small producers are allowed to deforest from five to 20 hectares, and made the conditions more flexible for this process to continue. Support for biofuel production from soya plantations and cattle grazing for beef export encouraged the opening up of new lands, with people using fire to clear forests for farming.

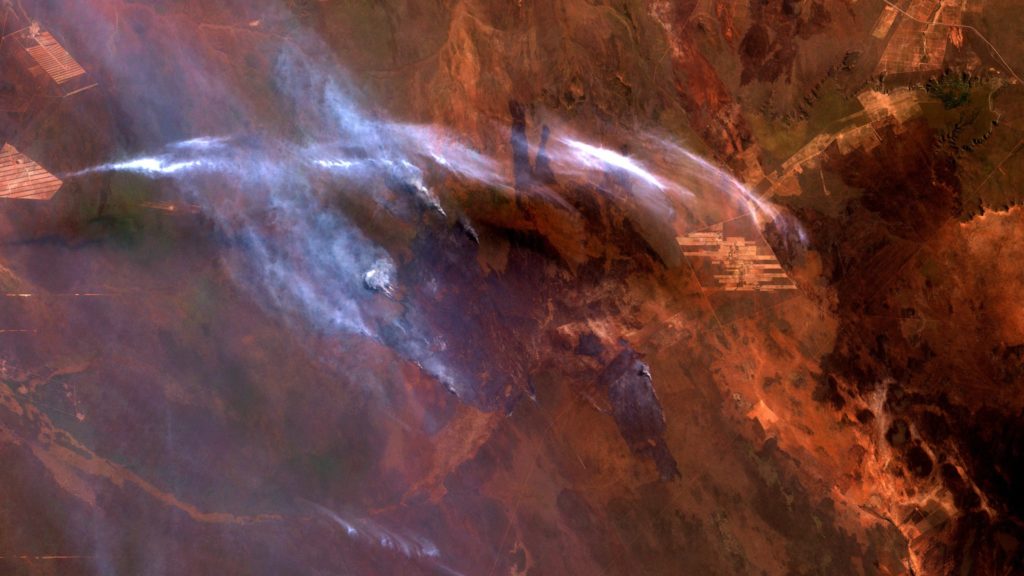

Between August and September 2019, Bolivia was wracked by the worst forest fires of the last two decades. A total of 3.6 million hectares were burned, and two reports showed that 57% of these fires were set in state-owned lands (which are largely composed of protected areas) and indigenous titled territories.

The push to expand agriculture has continued with Bolivia’s new government. Shortly after Morales resigned on November 10 2019, the legislative assembly of Beni – a lowland region – approved a law which would open 42% of the land to farming and industrial activities. On December 16 2019, Beni’s Indigenous declared a state of emergency.

Indigenous autonomy in the balance

By granting autonomy rights to indigenous people, the state would effectively recognize their right to govern themselves in matters related to the land and natural resources. Without this, people have no real control of their territories, and there is little that indigenous people can do to control environmental degradation.

Out of 33 claims for territorial self-government that were raised between 2009 and 2019, only three have been approved by the Bolivian government. Our research suggests that the main reason so few have succeeded is the new laws enacted during the Morales era, which make autonomy claims a complex and cumbersome process.

We’ve been working with the Monkoxi Indigenous Nation from the Bolivian lowlands since 2013, to help advance their claim to political autonomy in their territory. The Monkoxi belong to one of the 30 groups that are still waiting for their rights to be recognized, having initiated the legal claim in 2009.

Bolivia is now in the hands of an interim conservative leader, Jeanine Añez, who has been accused by indigenous rights organizations of holding strong anti-indigenous convictions.

Since expansion of the farming frontier was agreed between the right and Morales while he was in power, it’s doubtful the former will change this arrangement if they remain in power after general elections in May 2020. The pending autonomy claims that would allow indigenous people to consolidate their territorial control are also likely to stagnate.

The recent history of Bolivia shows the danger of allowing the fight for indigenous rights and climate action to be co-opted. To ensure that indigenous rights and climate change remain high in the next government’s agenda, indigenous peoples must work hard to reunite and recover the independence that they once had from mainstream politics.

Author Bios:

Iokiñe Rodríguez is a Senior Lecturer in Environment and Development at the University of East Anglia and Mirna Inturias is a Lecturer in Environmental Justice, at Universidad Nur.