Cathleen Barkley sits in a chair by the bay window of her office, clutching a sheet of paper. “It’s bleak,” she says, eyes skimming over numbers that don’t add up. “If tomorrow, all that funding was gone, we’d be a skeleton crew.”

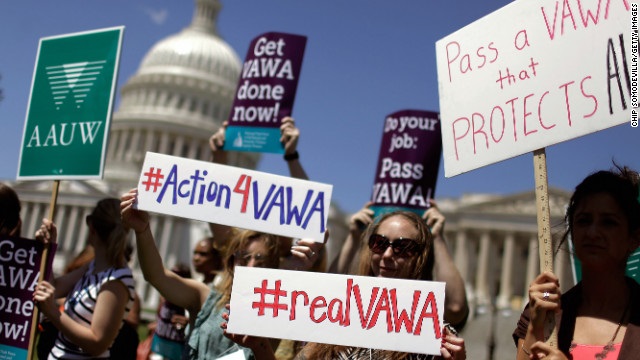

Barkley is the Executive Director of the Vermont-based non-profit H.O.P.E. Works, one of many rape crisis organizations across the country in jeopardy of losing their financial foothold if the Trump administration moves forward on its plans to eliminate the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). Since it was passed in 1994, VAWA has allocated billions of dollars to the investigation and prosecution of violent crimes against women. It has also provided as much as $600 million a year for grant programs aimed at reducing and preventing domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking, and dating violence.

Barkley looks down at the list of her employees that she holds in her hands, frowning. If VAWA is eliminated, her organization will lose half of its $600,000 operating budget. “Youth advocate: poof, for that position there would be no funding,” she says, moving down the list. In all, she would have to lay off most of her 10-person staff, and many programs they offer would be slashed. At a time when increasing numbers of survivors are reaching out to H.O.P.E. Works, such dramatic cuts would hurt a vulnerable community of people who already have limited options to find help.

Over VAWA’s lifetime, partner violence has decreased 64 percent, and both men and women are reporting their assaults at higher rates. Homicide by an intimate partner has decreased 34 percent for women and 57 percent for men. In its first six years alone, VAWA saved $14.8 billion in averted social costs to taxpayers.

“The national dialogue around sexual violence is unprecedented,” Barkley says, citing VAWA’s role in the societal shift. “And the result of that is that more people are reaching out for help. It’s a cruel irony that at the same time that people are getting switched on to this issue, a main funding source for rape crisis centers is in jeopardy.”

When someone—most often a woman—calls H.O.P.E. Works’ 24-hour hotline, it’s because they’ve been hurt. Some have been made to feel worthless by an emotionally abusive partner. Some are scared that their lives are in danger, calling from the bathroom while their abusive spouse bangs at the door. Some have been raped and are convinced that they deserved it. Some are calling while on the way to the hospital, hoping someone will stay with them while they get a rape kit done.

What these callers find is a crucial supportive resource. H.O.P.E. Works offers them legal advocacy, accompaniment at the hospital, short-term emergency housing, support groups, clinical therapy, and empathy—something that is often in short supply, as demonstrated by the mere proposal to eliminate VAWA.

“We had an advocate with a survivor who said, ‘You were the best part of the worst day of my life,’” Barkley recalls, a sad smile playing on her lips.

If the Trump administration follows the rules, the proposed elimination of VAWA will have to go through a budgeting process, meaning H.O.P.E. Works won’t actually see a reduction in funding until 2018 or 2019, potentially giving them time to find alternative funding sources. However, Trump’s own refusal to divest from his business interests—a violation of the constitution—reveals his attitude toward the law, calling into question whether his administration will follow standard procedures.

“We’re seeing how the rules seem to be an afterthought [for Trump], if at all—so that’s a little worrisome,” Barkley says.

Since it was originally passed 22 years ago, VAWA has always had bipartisan support—at least it did until 2013. During VAWA’s most recent reauthorization (which happens every five years), Democrats included language that expanded protections to LGBT, Native American, and undocumented survivors. Republicans responded by revoking their support and stalling the reauthorization for more than a year.

“I never would have thought I’d see the day when I’d wax nostalgic for George Bush,” Barkley says, laughing and shaking her head. During the Bush years, H.O.P.E. Works expanded greatly, offering new programs and purchasing and renovating a facility. Now, if the funding cuts come to fruition, she may have to sell their facility.

“Everyone agreed that ending violence against women and men and children is important. Now, how that’s up for debate? I don’t know,” Barkley says, looking down at the wooden table between us, her hands folded gently on top of one another. “It’s really scary.”

Kiera Hufford, a survivor of intimate partner violence, echoes Barkley’s thoughts. “If there are cases like Brock Turner that can happen under Obama’s administration when he actively respects women, then what’s going to happen now when Trump doesn’t?” she asks, referring to a recent sexual assault case that highlighted the failure of the justice system to protect survivors.

As the historic participation in the women’s marches after Trump’s inauguration proved, many women—including survivors and those who support them—are angry and ready to channel that energy into helping organizations like H.O.P.E. Works find a way forward.

For Barkley, her priority is finding alternative funding sources so that if VAWA is eliminated, H.O.P.E. Works won’t have to close its doors. “I’m not going to go down without a fight,” she says. “We’ve had the same hotline number since the 70s. Somebody is going to answer it. It just might not be the way we’re doing it right now.”

Sarah Wilkinson is a senior Professional Writing major at Champlain College. She’s had fiction and creative nonfiction published in a number of journals, including Atticus Review and Litro, among others. This piece about H.O.P.E. Works is part of Sarah’s capstone project, a collection of essays, stories, and articles that explore different power structures and the impact they have in the lives of all people.