On December 12th in Burlington, Vermont, Toward Freedom is hosting An Evening with Investigative Journalist Greg Palast – Why We Occupy: How Wall Street Picks the Bones of America

The following is an excerpt from Greg Palast’s new book, Vultures’ Picnic: In Pursuit of Petroleum Pigs, Power Pirates, and High-Finance Carnivores.

***

It’s all my fault, because I’m such a cheap bastard. I was told to rent a white van, something nondescript that painters or a handyman might use and wouldn’t be noticed parked at dawn on a road where only BMWs and Carrera 95s play.

It’s all my fault, because I’m such a cheap bastard. I was told to rent a white van, something nondescript that painters or a handyman might use and wouldn’t be noticed parked at dawn on a road where only BMWs and Carrera 95s play.

But I was afraid BBC wouldn’t pay for the van rental (I was right about that) and so here I was in the Red Menace, my fourteen-year-old busted-up Honda with the BRAKES idiot light on.

Anyway, I won’t move. I can wait you out.

Well, maybe I can. It’s freezing insane cold and the Dunkin’ Donuts coffee is cold, and I have to urinate out the last three cups I killed waiting on The Vulture to drive through his estate’s electronic gate to his “work” so I can somehow tail him unseen in my ridiculous red car. And now God is snowing on me. Thick, nasty, wet, heavy predawn snow, so everything turns white except my red beater. I might as well stick a flashing sign on the hood: I AM ON A STAKEOUT. I AM LOOKING FOR YOU.

We started at four A.M. It looks really glamorous on-screen when we broadcast these stories: the dramatic long-lens footage, then the jump and the confrontation. But after four horridly cold hours, there is nothing glamorous, just my bladder screaming at me. Badpenny calls from our Toyota, staked out in front of Vulture’s office building. Same issue— she and Jacquie have to pee. So now they could blow the whole story because God forbid they should just squat behind a tree and make some yellow snow. The women insist on porcelain and have to leave their post.

All right, damn it, find a gas station but don’t let them see you. Ricardo is cuddling his camera. His baby. Ricardo is calm. Ricardo is always calm. He’s just back from Iraq, where calm kept him alive. Ricardo is never hungry; Ricardo is never cold and never needs to urinate. Whatever drug he’s on, I want it. I tell Ricardo, “We stay.” Why? If God doesn’t give a rat’s ass about The Vulture and what he does for a living, what he’s done to Africa, why should I? Well, fuck God.

If I were a psychologist, I’d say I’m here because my father worked in a furniture store in the barrio in Los Angeles, selling pure crap on layaway to Mexicans; then later on, he sold fancier crap to fancier people in Beverly Hills and he hated furniture, and I hated the undeserving pricks and their trophy wives who bought it. I could smell their cash and the smell of the corpses they stole it from. They were all vultures, and the rest of us were just food.

So there you have it. My story, my motivation: resentment, envy, revolutionary fervor, whatever.

But I’m not a psychologist. I’m a reporter. And apparently one with a tiny, if fervent, international reputation: Just this morning I got a request from another young man, this one from Poland, who wants to join our investigative team. But instead of the usual résumé, Lukasz the wannabe journalist writes from Krakow that he has my BBC press pass, my notebook, and my laptop, which he’d stolen at London’s Heathrow Airport. Rather than money, he wants the job. It wasn’t ransom: If I said no to the job, he’d return the pass and notebook anyway. But he’d already junked the computer after cracking my security codes. I could use a guy like that.

But I don’t ask why I’m here. I know why I’m here. It’s because of what our Insider said on the tape about Vulture: Eric’s gone over to the Dark Side.

Las Vegas

The two-grand-a-night call girls are wandering lonely and disconsolate through the Wynn casino,

victims of the recession. Badpenny, dressed full-on Bond Girl, is losing nickels in the slots and humming Elvis tunes.

Badpenny’s assigned job here is to look good and get information. She’s good at her job. A tipsy plaintiffs’ lawyer is telling her, “A woman as beautiful as you should be told she’s beautiful every five minutes.” His nose dips slowly toward her cleavage. I didn’t know there were guys who still talked like that. Well, good. Take notes, Penny.

My own assignment is to hook up with Daniel Becnel. Becnel is just about the best trial lawyer in the United States. He doesn’t have an office in Vegas or New York. He puts out his shingle at the ass end of Louisiana, at the far end of the bayous, where he defends Cajuns like himself, and that includes the wildcatters out on the Gulf Coast oil rigs.

I have just come back from the Amazon jungle, where I was tracking Chevron’s operations. Chevron Petroleum monopolizes deepwater drilling in the Gulf of Mexico.

Maybe Becnel and I could trade information. It’s April 20, 2010. Hitler’s birthday and my ex-wife’s.

I found Becnel—far from the gaming tables and looking unpleasantly sober. There was an explosion back home. A rig blew out and was burning. The Coast Guard called him. They want his permission to open an emergency safety capsule they’d found floating in the Gulf. The Guard assumed maybe a dozen of his clients who had been working on the Deepwater Horizon platform were inside, cooked alive. The sound on the TV above the bar is off. The high, black rolls of smoke rising out of the BP oil rig remind me of my own office when it burned.

Something is very wrong in this picture. All I can see are a couple of fireboats pointlessly shpritzing the methane-petroleum blaze with water. What the hell? Where are the Vikoma Ocean Packs and the RO-Boom? Where is the Sea Devil?

Because of my screwy career path, I happen to know a lot about oil spill containment. And I know a lot about bullshit. This isn’t spill containment, this is bullshit. Here is a skyscraper on fire, and the firemen show up with two bottles of seltzer. How could they do this? How could British Petroleum, the oil company with the green gas stations, with the solar panels on the cover of their annual report, that kissed environmental groups full on the mouth by breaking ranks with Exxon to decry global warming . . . how could Green BP savage and slime our precious Gulf Coast?

The answer: BP had lots of practice. By the next day, CNN’s Anderson Cooper and an entire flock of reporters ran down to the Gulf to take close-ups of greased birds and to interview that mush-mouthed fraud, Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal. But I know something the other reporters don’t know: The real story about the BP blowout is in the opposite direction, eight thousand miles north.

I have in my files a highly confidential four-volume investigation on the grounding of the Exxon Valdez in Alaska, written two decades ago. The report concluded, “Despite the name ‘Exxon’ on the ship, the real culprit in destroying the coastline of Alaska is British Petroleum.” I have a copy because I wrote it.

That was my last job. The job that defeated me: after years as a detective-economist, investigator of corporate fraud and racketeering, this was the case that ruined the game for me. The important thing, the hidden story calling me north, is that the Deepwater Horizon disaster was born right there on the Alaska tanker route. Here’s why: BP did the crime but didn’t do the time. Exxon got away pretty cheap, sure, but BP walked away stone free, not one dime from its treasury, not one drop of oil blotting its green reputation. So I quit.

But for now, from the casino, Badpenny is booking me a flight on Alaska Airlines and calling around for a Cessna Apache to charter to the Tatitlek Village on Bligh Island. The network would have to trust me on this. I know that the key to exposing the cause of the Gulf spill is there in the Tatitlek Native Village. I need to speak with Chief Kompkoff.

Somewhere off the coast of Azerbaijan

Just after leaving Las Vegas, Badpenny received an e-mail marked “Re: Your Palast Donation,” coming from, weirdly, a ship floating in the Caspian Sea near BP’s Central Azeri oil drilling platform, that is, somewhere off the coast of Azerbaijan in Central Asia. It read, “Would not be wise for me to communicate via Official IT system.”

We replied, “Understood,” and waited.

When the Deepwater Horizon well blew out in the Gulf, BP acted shocked. Just six months before the Gulf explosion, a BP vice president testified to Congress that the company had drilled offshore for fifty years without a major blowout. When the big well did blow in the Gulf, the company said that nothing like this had ever happened before. That is, nothing they reported. Weeks after we received the first message from the ship in the Caspian Sea, we located our terrified source in a port town in Central Asia; and he told us BP’s claim to Congress was a load of crap. He himself had witnessed another deep water platform blowout. He seemed really nervous. And for good reason.

I didn’t know where the hell I’d get the budget to get to Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, but Badpenny booked it without asking. “I know you’re going, so let’s not discuss it.”

Rolling Hills, New York

Cold coffee in a snowstorm wasn’t what I had in mind. The original plan was not so screwed up. I’d enlisted that crazy bastard John McEnroe (really) to help us get consent to get onto The Vulture’s property. From satellite photos of Vulture’s estate, we could pick out a tennis court not a hundred yards from his entranceway. To get cameras onto his property, we would show up in tennis whites with our smiling crew from the new reality show So You Think You Can Play Tennis! Starring John McEnroe! Would Vulture like to swing a racket with the champ?

But our timing went to hell. Tennis balls in a blizzard? Forget it. Now London is calling on Ricardo’s cell. BBC Television Centre. Trouble. Some flunky working for Dr. Eric Hermann aka The Vulture seems to have spotted a red car at the end of his driveway and called Dr. Hermann’s PR firm in England, where it’s already late morning. The Vulture’s flak squawked at the BBC

news desk, “Is Palast on a ‘vulture hunt?’” Jones, my producer, says he told The Doctor’s PR, damn right. Jones adds, “A farkin red car!?” Forgive him, he’s Welsh.

Cold, and now a bad, bad thought: He’s slipped us. That’s easy to do from a house bigger than the Vatican— twenty thousand square feet with nine bathrooms (we checked the tax records). Worse, the aerial photo revealed acres of woods on the blind side, which leads right to the back of the Doctor’s office tower. And the profile said Dr. Hermann was a serious marathoner. This guy could merrily lope right across his private forest to his office, chuckling at the schmuck in the red car. Or maybe he could apparate there like a Harry Potter warlock.

Badpenny and Jacquie swore over the cell that they hadn’t spotted one face from their photo sheet going into the building; but that could have been due to their inexcusable porcelain pit stop. I drove the Red Menace too fast on the ice around the back roads to Hermann’s office. We already had the layout. Badpenny had done the recon a week earlier. She deliberately misaddressed an envelope, made a “delivery” to their office, acting like a confused ditz while mentally mapping the place.

Now, as we’re huddled against the snow, she tells Ricardo that if we could get by the distractible security guy with some BS, we could walk right into the fourth-floor office suites of The Vulture’s company, FH International. Inside the building—the security desk was oddly empty—Ricardo hopped the elevator, pulled his ultrasmall digi-cam out of the sports bag and clicked on the microphone. A well-dressed woman riding up with us asked, “Surprise for someone?” It was. But the surprise would be on us.

We hustled around the fourth floor with Badpenny’s hand-drawn map, looking for the FH suite doors. Around and around the building halls we went, three times, comically lost. Then I noticed a huge white spot on the hallway wall: The big sculpted name plaque of FH International had been unbolted from the wall, the office number removed and the door locked.

Gone. In just hours. A billion-dollar group of international hedge funds . . . pfft! I leaned against the door, just exhausted, just defeated. Then I heard voices. Behind the doors. The Vulture had his employees locked in.

Now this was slapstick, this was the land of the weird: multimillionaires cowering under their desks in the dark, afraid of the guy in a red Honda. I was honored. All this, the unbolted sign, the muffled millionaires, all to avoid answering this one question, What, or who, is the Hamsah?

Liberia, West Africa

With The Vulture’s crew still pretending they were invisible and building Security hustling us down the elevator, we knew the only way to get an answer to our question was to get inoculations and emergency visas and head out to Liberia. BBC was not happy about the cost of the airfare and I don’t blame them, but I had to speak to the President herself.

Thirty-six hours after the stakeout in the snow, we were sweating at customs in Accra, in West Africa.

“WELCOME TO GHANA. WE DO NOT TOLERATE SEXUAL PERVERSIONS.” Well, as a national motto, that’s a cut above In God We Trust.

It wasn’t like the last time I tried to get a transfer into Liberia, during the civil war, in 1996, when the capital’s airport was just a bunch of holes, bomb craters. Back then, the only flight in was chanced once a week by two Russians running contraband on an old Tupolev turboprop. I was told I could hitch a ride for two bottles of vodka. I asked if I could give them the vodka after we landed. Nyet.

Now I’m flying in on Ethiopian Airlines and taking the vodka for myself despite my promises to cut that shit out. If you can’t name the capital of Liberia, relax, this isn’t a test. Most Americans don’t learn the capitals of foreign lands until the 82d Airborne lands there. Kabul. Mogadishu. Saigon. Answer: It’s Monrovia. The capital of Liberia is named after the U.S. president James Monroe, who helped former American slaves give birth to the longest-lived democracy in Africa, founded 1847. Its democracy dropped dead when, in 1980, a Corporal Sam Doe marched every member of the elected president’s cabinet out to the nearby beach, tied them to poles and shot them, TV cameras rolling. Ronald Reagan was elated and helped the killer dictator Sam Doe turn Liberia into a Cold War killing zone. One in ten Liberians would die.

Ricardo and I arrived in Liberia without two clues to rub together. But Ricardo had one. He had just learned some Arabic the hard way: As an involuntary guest of some bad guys in Basra, Iraq. He said, “You know, Hamsah in Arabic means ‘Five.’” The symbol is Lebanese. Of course.

Motown

By the age of fifteen, Rick Rowley was doomed. Born in the middle of Nowhere, Michigan, a wasteland of rust and snow so awful we let autoworkers have it. As a kid, Rick would put his head down on the railroad track and wait for the rare vibration of a train on the move far away. He was fifteen years old on the day he got up and followed the hum down the track. He walked for over two hundred miles, surviving on peanut butter and Wonder Bread all the way to Motor City: Detroit. Rick wasn’t running away; his parents were OK. He was running to something; who knows what the hell it was. Rick never made it back to Nowhere.

He listened. He looked. And he found that other people’s stories were more important than his own. Along the way, he picked up a small camera that listened and looked with him. He found more stories in Argentina inside the IMF riots, then six months in the Yucatan jungle, learning Spanish with the Zapatista guerillas, who named him Ricardo, then somewhere along the way a stretch at Princeton University, then several stints in Iraq, in Afghanistan, and in Lebanon, with Hezbollah. He held the little thing, that digital camera, weirdly, cradled like an infant. The first time he filmed for BBC News, at my insistence, Jones said, “What’s that? Some kind of toy camera?” No, it’s my gun. Ricardo doesn’t like to talk about himself. It took three deadly potent drinks at a bar in West Africa to find out about the railroad track, Hezbollah, Princeton. He’s off now, un-embedded.

Ignoring Jones’s advice, he made it back to Iraq to catch warlord Abu Musa’s last arrogant words before Abu was blown into small wet pieces. Rick’s a lucky guy. So far.

Tatitlek Village, Bligh Island, Alaska

Chief Gary Kompkoff stood on the beach, watching the Very Large Crude Carrier VLCC Exxon Valdez bearing down on Bligh Reef. Kompkoff was wondering, What the hell? It was near midnight, starlit and clear. As the ship’s shadow loomed, the whole village joined him on the

beach, wondering, What the hell?

Kompkoff told me he thought it was some kind of dumb-ass drill. Even a drunk couldn’t miss the turning halogen warning beam lighting up their faces every nine seconds.

It wasn’t a drill.

Now, don’t get the idea that these were just a bunch of dumb Indians stunned by the appearance of the white man’s supertanker. They didn’t have televisions, but they did have training in oil spill containment.

Containing an oil spill on water isn’t rocket science. Whether it’s a busted tanker or a blown well, you do two things: First you put a rubber skirt around it. The skirt is called a “boom”. Then you bring in a skimmer barge with a big sucker hose hanging off it and suck up the oil within the rubber corral; or you can sink it (“disperse” it with chemicals); or you tow it away and set it on fire. There are lunatic variants of course, most employed by BP. In 1967, the Torrey Canyon, in the English Channel, took a shortcut meant for fishing boats and broke up. It was the largest tanker spill ever. British Petroleum called in the Royal Air Force, which bombed the hell out of the slick as it floated across the Channel to France. The RAF was as effective on the floating oil as they are on the Taliban. Oil Slick: 1. RAF: 0.

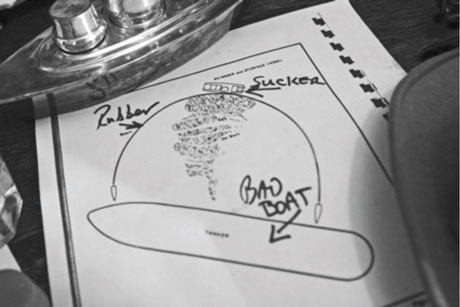

Here’s a dirt-simple illustration of how you contain an oil slick from a busted tanker.

It’s roughly the same for a well blowout. You see in this photo a small cartoon tug dragging the rubber skirt, called a Vikoma Ocean Pack, around the ship, while the other little boat, a Sea Devil skimmer, sucks up the blotch, the floating oil.

Here’s the irony, or the crime, take your pick: I obtained this diagram from Alyeska, the company responsible for containing and cleaning up oil spills on Alaskan waters, no matter who owns the tanker. Alyeska is a combine of companies and the politically helpful cover name for its senior owner, British Petroleum. Exxon is junior. Some junior.

The tanker spill illustration is from the BP-Exxon official OSRP (Oil Spill Response Plan) for Prince William Sound, Alaska, published two years before the Exxon Valdez grounding at Bligh Island, Tatitlek. The oil companies’ top executives swore to this plan under oath before Congress.

It was, I admit, a beautiful plan. It had everything: suckers and rubbers all over the place, and round-the-clock emergency crews ready to

roll.

Simple simple: Surround with rubber and suck. The Tatitlek Natives could have done that lickety-split and you would have never heard of the Exxon Valdez.

But could have are the two most heartbreaking words in the English language. The Natives were the firemen with the equipment. It was right in the plan. They just stood there. Why? During my investigation right after the Exxon spill, Henry Makarka (“Little Bird”), the Eyak elder, flew

me over to the village of Nuciiq, abandoned now. He told me, “I had to watch an otter rip out its own eyes trying to get out the oil.” Henry’s a sweet guy, eighty now. But in case I missed the point, he added, “If I had a machine gun, I’d kill every one of them white sons of bitches.”

He didn’t say, “white.” He used the unkind Alutiiq phrase, isuwiq something, bleached seal.

I needed him to tell me straight, no BS, what the hell happened in those meetings between the Chugach chiefs and the oil company chiefs twenty years earlier, to back up my suspicions, or to tell me I had hit another dead end. It was not a conversation he was happy to have, especially with a bleached seal investigator.

The Eyak, Tatitlek, and other Chugach Natives have lived in the Sound for three thousand years, maybe

more, the very last Americans to live off what they could catch, gather, hunt. It was March 24, four minutes after midnight, 1989, when Kompkoff witnessed the moment when three thousand years of Chugach history came to an end, the moment when Satan collected his due for the Natives’ complicity, especially Makarka’s.

Los Angeles, California

Why am I flying all over hell? Why am I chasing down kooky potentates and cowering hedge fund speculators, then schlepping you up to the Arctic and down to the Amazon?

Why am I writing this all down, dragging you along with me?

My publisher wants me to write a neat little book on one simple topic, like “oil companies” or “banks” or “Recipes from Sex and the City.” But the planet is not as simple as a quart of homogenized milk, all silky white.

It’s a mess, it’s a jumble. Get used to it.

That’s how it is. That’s how we work. I don’t get to say, Oh, please don’t send me that smoking information this week. And the weeks following the Deepwater Horizon disaster produced the heaviest shower of must-follow info in my career.

But, for the sake of clarity, and my sanity and yours, I will take you along with me, one investigative move at a time. Only in this first chapter, I want to show you how our work actually gets done, following down several tracks at once. Stumbling over each other, knocking our heads into walls (I get my best ideas that way).

I’m what Dr. Bruce, my high school science teacher, would call a honey dipper. Before Dr. Bruce earned his doctorate, he took one of the few jobs a black child in the Deep South could grab to earn a few dollars, honey dipping. When someone dropped a wedding ring or a wallet down into the outhouse toilet, Dr. Bruce would dip into it with his bucket, pull up the stuff and go through it carefully. He got to enjoy it. So have I, dipping in, squeezing it through our investigative filters, finding the good stuff. There’s not one topic, but there is only one story: I chase different turds around the planet, but it’s all the same shit.

There is only one story: the story of Them versus Us.

THEY get homes bigger than Disneyland, WE get foreclosure notices.

THEY get private jets to private islands, WE get tar balls and lost futures, and pay their gambling debts with our pensions.

THEY get the third trophy wife and a tax break, WE get sub-primed.

THEY get two candidates on the ballot and WE are told to choose. THEY get the gold mine, WE get the shaft.

Them versus Us: that’s my career, my obsession—and my tombstone (“THEY FINALLY GOT ME.”)

This book, this journey, is a quest to unmask The Beast, the monstrous machine that works ceaselessly

to take from Us to give to Them.

Greg Palast is the author of the New York Times bestseller The Best Democracy Money Can Buy.” View Palast’s reports for BBC TV and Democracy Now! at gregpalast.com.