In the immediate aftermath of Trump’s electoral victory, progressives quickly remembered radical labor activist Joe Hill’s evocative call to his supporters on the eve of his execution—“don’t mourn, organize.”

But Hill’s command is more of a battle cry than a battle plan. The most difficult question is still front and center: What is the best way to organize against Trump’s regime?

The Base is Not Enough

Clinton outspent Trump on field staff and ran a more traditional get-out-the-vote campaign, even in states like Florida and Pennsylvania, where Trump ended up winning. But the strategy was based on a faulty premise. They believed that the current base of committed Democratic voters—a new rainbow coalition of progressive whites, people of color, queers, a bare majority of union members, and the educated liberal elite—is enough to safely ignore its right-drifting constituents, the white working class, and still win.

Others agreed with them. Civil rights leader Steve Phillips’ recent book, Brown is the New White, makes the case that the Left has been over-reliant on targeting white swing voters. It should, in his analysis, refocus its efforts on a younger, diverse “new American majority” rooted in communities of color. Similarly, the labor journalist Rich Yeselson’s much-debated article “Fortress Unionism” offered a similar “base-only” strategy. His hunker-down-and-wait proposal focused on strengthening existing locals and areas of high union density, but not necessarily new organizing. In particular, he stresses the importance of defending the highly unionized geographies of Las Vegas, Los Angeles, the Bay Area, Seattle, and New York City, all places Clinton won easily.

Echoes of these arguments have been voiced by many progressive organizers since the election. In general, distrust of whites of all classes—only 37% of whom voted for Clinton—but especially a deep skepticism toward the white working class in particular, has led many progressives to believe that attempted recruitment of new allies outside the safe base is a dead end.

Veteran organizer and author Jane McAlevey could not agree less. In an interview about her recent book, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Guilded Age, she is unequivocal about organizing in the Trump era: “Our objective has to be spending 90 percent of our time working with and helping the undecideds sitting out there understand who’s really to blame for why they feel so much pain.”

McAlevey’s position recalls an old common sense, yet one that is in short supply today—any serious campaign requires identifying those on the fence, vulnerable to recruitment by the opposition, and turning them toward your side. Her position should be considered especially in light of how disastrously wrong the national electoral polls and Clinton’s internal analytics were in the Midwest and Rust Belt states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Michigan. There, Trump breached the traditional “blue wall” and won votes that Clinton thought were in the bag. With union households voting Democratic at just 51%, the lowest level since 1980, the fortress gates may not be as solid as Yeselson presumed.

The labor and racial justice organizer Bill Fletcher Jr. called the election a “revolt against the future,” by which he means “a return to the era of the ‘white republic.’” This is true, but it is also a revolt against the future in another way.

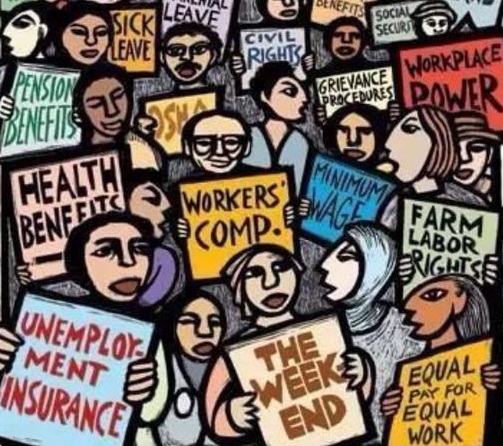

Trump’s America promises to turn back the clock on progress made by union, community, and environmental activists. For example, his Supreme Court will pass something like the proposed anti-union Friedrich’s bill, which would have effectively crippled the ability of public sector unions to collect dues. He will appoint a hostile National Labor Relations Board and pave the way for national right-to-work legislation. In the end, workers will live in a world far more like the America before labor unions won the right to legally organize. When this scenario happens, and it is already beginning, what is the most effective way for organizers to respond?

Resist to Exist

When Trump’s promised “law and order” regime comes to attack the right of social movement organizations to exist, the response will have to come in the form of rule-breaking and civil disobedience. What examples can we find that are instructive?

Before labor unions won the legal right to bargain collectively in the mid-1930s—a move made to contain labor power more than to bestow it legal standing—mass strikes, disruptions, and violence were common ways for workers to express grievances. But this militant activity continued even for decades afterward. Teachers, for example, who were exempt from the right to organize and bargain, built their unions through mass strikes—in 1968 alone US teachers struck 112 times. They didn’t walk a picket line legally until 1975, yet by then the union counted nearly two million dues-paying members.

Is it possible that Trump’s demagoguery will leave no option but renewed militancy and action?

It seems unlikely labor will return to these strategies, even if they seem necessary. Recent picket lines outside of fast food restaurants, Walmarts, and at Chicago public schools belie the fact that strikes have all but disappeared in this country compared to their heyday at the turn of the last century.Labor’s flagship campaign of the last decade has been the Fight for $15, which doubled the minimum wage among low-wage workers in major cities. But that effort has become almost exclusively a public relations campaign to convince lawmakers to raise the floor, a strategy likely to fail with greater republican control of government. Strengthening labor law within the highly-unionized states, the so-called fortresses, is not even an option, as federal labor statutes typically override local policy.Moreover, some major labor unions have already made overtures to collaborate with Trump’s administration, hoping to contain the worst rather than consolidate a campaign to fight.

History, however, does provide a modicum of hope. As labor union leadership became more entrenched and bureaucratic, and opposed to workplace activism, regular rank-and-file workers fought back. Throughout the 1970s, an average of almost 300 large-scale work stoppages happened every year. As a point of comparison, in 2015 there were twelve.But there is nothing particularly special about that time that would ward against the same level of activity today.

In fact, disobedience seems to be in high supply right now. Hundreds of unpermitted marches have taken place across US cities denouncing Trump’s racist, sexist, classist agenda, and more are planned into January. Mayors in at least four major cities have declared their intention to not cooperate with his proposed mass-deportations of migrant workers and refugees. Spontaneous groups have begun planning to shut down and otherwise undermine Muslim registry locations should that horrible plan come to fruition. Others are promoting a national “sick out” on inauguration day. And then there’s Standing Rock, a protest so committed to outright illegal resistance it has even struck fear into local law enforcement agencies that are now retreating on their commitments to defend the pipeline company.

Back to the Future

The organizer and author Bill Fletcher Jr. is right, as usual; this is a revolt against the future. Rather than dig deeper into our own familiar communities, we must go back to the uncertain future. That requires experimenting with the skills of organizing the undecideds, some of whom voted for Trump, and never taking our eyes off them. There are, of course, people doing this already. Groups like the Rural Organizing Project in Oregon, some strong unions in the South, and others are already focusing on recruiting more white workers into social justice movements. In Vermont, where I live, rural white workers are easy to find, and the handful of grassroots organizations here tend to prioritize organizing them into fights for healthcare, paid sick days, political change, against fracking, etc. Most recently, some of these organizations have collaborated to help welcome Syrian refugees into Rutland VT. It will not be easy to bring undecideds into an escalated fight. But it is the job of organizers to help people understand what is necessary to win, not offer them something comfortable to do.

The fundamental organizer nostrum—that people are transformed when they are brought through a struggle, not when they are simply offered different facts, interpretations, or empathy—requires action to make it meaningful. Progressives must seek out swingable Trump voters not because it is right, or because forgiveness is cathartic, but because we simply can’t win without them. There is no path to freedom that circumvents white supremacy; we must tread through it carefully. The opposite theory, that our base is big and strong enough to leave the rest alone, has always failed.

Jamie McCallum teaches Sociology at Middlebury College. His book, Global Unions, Local Power, examines campaigns of workers to organize across borders. He is an occasional labor and community activist. He would like to thank friends in and around the labor movement for their helpful discussions when drafting this article.