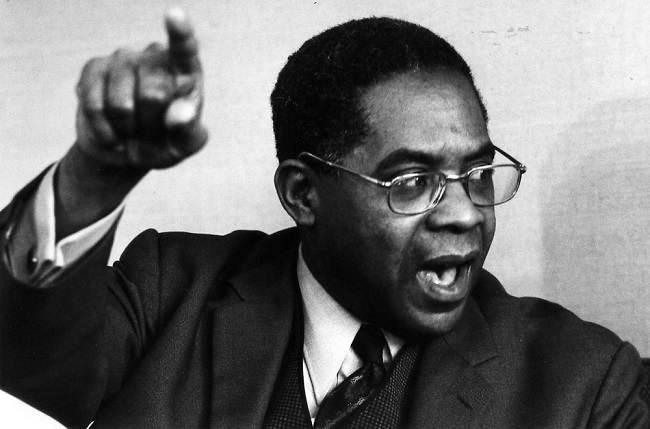

Aimé Césaire (1913 – 2008), the Martinique poet and political figure, whose birth anniversary we note on June 26, was a cultural bridge builder between the West Indies, Europe and Africa. A poet, teacher, and political figure, he had been mayor of the capital city, Fort-de-France for 56 years from 1945 to 2001, and a member of the French Parliament without a break from 1945 to 1993 — the French political system allowing a person to be a member of the national parliament and an elected local official at the same time.

With the end of the Second World War, the French Communist Party had one third of the seats in the Parliament of the newly created Fourth Republic. The French Communists were looking for potential candidates from Martinique where the Party was not particularly well structured. They turned to young, educated persons who had a local base. Césaire, with his Paris education and as a popular teacher at the major secondary school, fitted that bill. He was elected the same year to Parliament and to the town hall.

As the French Communist Party had a practice of tight party discipline, Césaire played no independent role in the French Parliament until he left the Party in 1956. However, his 1950 Discours sur le Colonialism, at the same time violent and satiric, became the most widely read anti-colonial tract of the times, calling attention to the deep cultural roots of colonial attitudes. After 1956, most of his efforts in Parliament were devoted to socio-economic development for Martinique. His strong anti-colonial efforts were made outside Parliament, especially in the cultural sphere. Nevertheless, as a member of Parliament he could open doors that poets do not usually enter.

Césaire’s wider fame was due to his poetry and his plays — all with political implications. His parents placed high value on education — his father was a civil servant who encouraged his children to take school seriously. Thus Césaire ranked first in his secondary school class and received a scholarship in 1931 to go to France to study at l’Ecole Normale Supériéure — a university-level institution which trains university professors and elite secondary school teachers. He was in the same class with Léopold Sédar Senghor and Leon Damas both from Senegal. They, along with Birago Diop also from Senegal, started a publication in Paris L’étudiant noir (The Black Student) as an expression of African culture.

One of Césaire’s style in poetry was to string together every cliché that the French used when speaking about Africa and turn these largely negative views into compliments. Thus he and Senghor took the most commonly used term for Blacks, Nègre, which was not an insult but which incorporated all the clichés about Africans and West Indians, and put a positive light upon the term. Thus negritude became the term for a large group of French-speaking Africans and French-speaking West Indians – including Haitian – writers. They stressed the positive aspects of African society but also the pain and agony in the experience of Black people, especially slavery and colonialism.

In 1938, just as he finished his university studies, Césaire took a few weeks’ vacation on the coast of Yugoslavia. There, he wrote in a burst of energy his Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (Notebook of the Return to My Native Land), his best known series of poems. Césaire also wrote on the Haitian independence leader Toussaint L’Ouverture as a hero, and later a play in 1963 La Tragédie du roi Christophe largely influenced by the early years of the dictatorship of Francois Duvalier. Césaire, who read English well, was interested in the writings of Langston Hughes whose poems were close in spirit and style.

In the 1960s, Césaire turned increasingly to writing plays, especially on the history of Haiti, as the earliest independent state of the West Indies. These were verse plays as the actors’ dialogues were nearly poems. As the French African colonies became independent in the 1960s, he stressed that the end of colonialism was not enough but that colonial culture had to be replaced by a new culture, a culture of the universal, a culture of renewal. “It is a universal, rich with all that is particular, rich with all the particulars that are, the deepening of each particular, the coexistence of them all.”

Rene Wadlow is President of the Association of World Citizens.