Joy ran high two weeks ago among students, environmentalists, businesspeople, and politicians as the news came in that Greystar Resources had revoked their application for a large-scale open-pit gold mine in the mountains of northeastern Colombia.

But just twelve hours later, Greystar intentions became clear – they were withdrawing that application to bring in a new one for a redesigned, underground mine. This short-lived but significant victory was possible thanks to the tireless efforts of the broadest, most diverse coalition in Colombia’s recent history. This coalition brought together an engineer’s association, committed student activists, the head of the local business federation, NGOs, teachers, environmentalists, and water utility employees.

Foreign investments in Colombia’s mining sector grew shyly in the 1990s, but in the eight years of former President Alvaro Uribe’s regime it skyrocketed in part due to a perception of safer exploration conditions. Even the Canadian government showed their interest in making Colombia prime for investment needs by having their International Development Agency (CIDA) draft Colombia’s mining law of 2001, granting generous privileges to foreign companies. Uribe’s disciple, current President Juan Manuel Santos has made resource extraction a centerpiece of his economic plan, deeming it the main “motor” of development and plans to follow the lead of Chile and Peru, two truly mining-oriented countries.

Santos’ strategy includes generous tax breaks to mining companies and modifying laws to be more “investor friendly.” It also involves persecuting traditional small miners – some who lack a mining title – aligning them with the neo-paramilitaries and guerrillas who mine illegally to fund their dirty work. Mainstream media plays into this dynamic by focusing on illegal mining but remaining silent about the large-scale corporate takeover of Colombia’s resources. Currently, 40% of Colombia´s entire area is under mining permits, some of it on environmentally protected land or indigenous and Afro-Colombian communal territories.

Into this mining binge came Greystar Resources, a Vancouver-based “junior” mineral exploration company, which typically explores potential mining sites, deals with the permitting processes, and then sells their acquisition to an actual mining company. Due to their lack of mining experience one could assume that their real business is financial speculation. Among its investors are International Financing Corporation – the World Bank’s private financing arm, and JP Morgan.

The company has mineral rights over 74,000 acres of land in the mountains of California and Vetas, two small and remote towns forgotten by the state where Greystar has invested in infrastructure and had brought promises of employment and progress. Many locals in that area badly want the mine.

The project is just 40 kilometers northeast of Bucaramanga, Colombia’s fifth largest city. Greystar plans to dig out an estimated 9 million ounces of gold, making it one of the largest gold deposits in South America.

But that gold happens to sit under the Santurban paramo, a tropical version of high moorlands. This unique ecosystem supplies water for Bucaramanga and 21 other towns. The proposed use of cyanide at the Greystar mine caught the attention of the region’s citizens, who see it as a major threat to their “liquid of life” source: water. Mineral extraction was also legally banned in paramos in the amendment to article 34 of the Colombian Mining Law in 2010.

Water vs. Gold

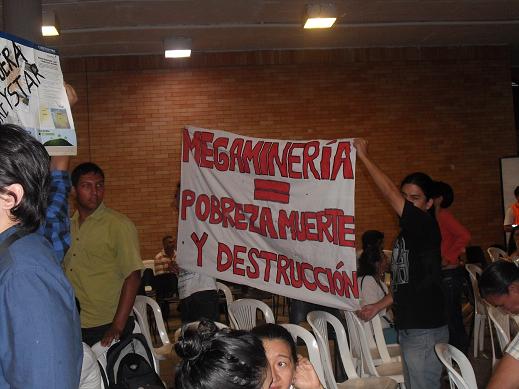

Besides the national effort to render all paramos mine-free zones, various environmental organizations in the Bucaramanga area worked for years to have Santurban declared a protected area, which would exclude mining, logging and cattle grazing from its grounds. More recently, opposition to the mining project gained ground when university students and other environmentalists joined the cause. These activists were not only concerned about the threat to their local water supply, but also about the sovereignty and long-term economic implications this mine represented within the national mining policy. They also realized that the need for water was shared by everyone, regardless of their political views. Therefore, the activists framed their anti-mining campaign through the unifying lens of water.

Following this victory, the economic federations of Bucaramanga, who, besides understanding the intrinsic environmental value of the Santurban paramo, came to the conclusion that damaging the city’s water source would have a more negative financial impact in the long term than the ephemeral gains of mining. The state engineers association also opposed the project. At this point, it became clear the general public sentiment in the region was that water was worth more than gold.

“Take to the streets in support of your treasure, the Santurban paramo”, called out members of the coalition during a public demonstration. Previous protests had seen low turnouts, but the issue became so well-known and the opposition so diverse, that over 30,000 Bucaramangans marched on February 24th, petitioning the Environment Ministry to deny Greystar’s license application. Around this time other segments of the government, including the Attorney General, publicly denounced the mine.

Now all eyes were on Bucaramanga. The ministry held a public hearing on Greystar’s case. There was a clear division between the small crowd from California and Vetas that was bused there by the company to support the project, and the large, mostly urban majority opposing the mine.

The majority of politicians, most prominently the state’s governor, explicitly called to shut down the project for its technical flaws and risks it posed to the community. Tensions ran high as the hearing progressed. Two attendees started a fight, giving the ministry a reason to end the hearing early. Unfortunately, media coverage of the event focused on the fight rather than on the almost unanimous resistance to the gold mine.

The hearing was a public disgrace to the company, whose stock value dropped 30%. To top it all off, Colombia’s energy minister and even Serafino Locono, a prominent oil-and-mining CEO, highlighted Greystar project’s flaws at a miner’s conference in Toronto.

Greystar decided to preempt the environment ministry’s decision on their license application and withdraw their request for the mining operation, only to announce later that they were reconfiguring their project to “address the concerns of the community”.

This company is just one of a group of businesses who are after Santurban’s gold. Their counterparts include Galway Resources and Ventana Gold Corp, which was recently purchased by energy billionaire Eike Batista. The success of these companies will likely be impacted by Greystar’s fate.

Ephemeral Coalition?

Coalition founders worked hard to bring everyone to the table, and found a common point of interest with their traditional political opponents in the belief that the public’s right to clean water takes precedence over private interests. Through their educational campaigns and public demonstrations, they slowly started gaining ground.

But this broad alliance against the mining project is not quite a movement, for it articulated under a temporary cause, and its members as a whole have little in common beyond their rejection of the mining operations. The coalition is a more of an interim union aided by the fact that elections are underway, so politicians sought an opportunity to seek supporters. Whatever its nature, this grassroots experience opened the door to a multi-party dialogue rarely seen in Colombia.

The most committed segment of the coalition – the students and environmentalists who oppose large-scale multinational mining – want to move the argument beyond the threat to Bucaramanga’s water supply. They see a need to adapt to the reconfiguration proposed by Greystar, and to deepen the debate to include other harmful effects the mine would bring, such as a deterioration of the area’s agricultural web and the loss of a local supply of gold for Bucaramanga’s thriving jewelry industry.

Publicly, the coalition has been very successful in bringing the Santurban case into the eye of the media hurricane, and forcing Greystar to change their strategy. Their ability to stop the mining project itself and to protect their beloved paramo remains to be seen.

Natalia Fajardo is a mining consultant for Cedetrabajo, a political analysis institute in Colombia. Cedetrabajo is a member of Reclame, Colombia’s national network of organizations facing large-scale mining.