Will the tragic deaths of over 60 Afghan girls change U.S. President Joe Biden’s trajectory for withdrawing U.S. forces from Afghanistan? It’s too early to tell, but he’s unlikely to change the tired old mantra of why U.S. troops were sent there in the first place—to fight the terrorists responsible for the 9/11 attacks.

Biden added in his April 14 announcement, “We defeated al Qaeda.” Like predecessors before him, he avoided the missing link that best describes U.S. motivations in Afghanistan: Securing control over the oil and gas of the nearby Caspian Sea, to be shipped by pipeline from Turkmenistan, through Afghanistan, and on to Pakistan and India. The TAPI pipeline (named for the countries it would traverse) was envisioned long before 9/11 and is still awaiting completion. Key to its success is securing its passage through lands occupied by warlords. The fiercest warlords of all—once deemed most capable of protecting the pipeline—are the Taliban. As recently as February 2021, the Taliban promised—once again—to protect the TAPI pipeline, described by The Diplomat’s Katherine Putz as a “monumentally important project.” However, Putz added, “It’s unclear whether it will ever be built.”

Below is an excerpt from my book, The Crash of Flight 3804: A Lost Spy, A Daughter’s Quest, and the Deadly Politics of the Great Game for Oil, which delves into the oil and gas connections to the bloody conflicts in Afghanistan, as well as in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and Israel. All sources are documented in the book.

Excerpt

Dick Cheney, as CEO of Halliburton before becoming Bush’s vice president, had certainly made it his business to know where the great oil and gas prospects of the world lay. He made a number of trips to Afghanistan to court the Taliban in 1998, knowing from firsthand experience that one of the greatest prospects in modern times lay in and around the Caspian Sea. The Washington-based American Petroleum Institute had called the Caspian “the area of greatest resource potential outside of the Middle East,” and Cheney readily concurred, telling a group of oil company executives in 1998, “I can’t think of a time when we’ve had a region emerge as suddenly to become as strategically significant as the Caspian.” Even after Unocal withdrew from Afghanistan in 1999, Cheney kept a watchful eye on developments in the region, especially after Bush chose him as his running mate in 2000.

During his presidential campaign, Bush himself let the cat out of the bag about his priorities if elected president. He told a Boston audience during his first presidential debate on October 3, 2000: “I want to build pipelines to move natural gas. . . . It’s an issue I know a lot about. I was a small oil person for a while.” Indeed, compared to the Rockefeller-spawned ExxonMobil and Chevron giants that invariably cornered the most lucrative oil and gas markets in the world, Bush’s Zapata Oil was small potatoes. His ascent to the presidency promised more open doors to the “small oil people” in the former Soviet republics in the Caspian Sea region, and in Iraq. Under Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz even admitted to the Guardian in May 2003 that everyone in the oil business knew Iraq was rich in oil. Once in office, Bush appointed so many oil executives to his cabinet that the Oil and Gas Journal gushed, “From industry’s perspective, the casting of the lead roles couldn’t be better.” Besides Cheney as Bush’s vice president, there was Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s national security advisor, who had served on the board of Chevron and had once been honored by having a Chevron oil tanker named after her. (The name was removed after she joined the Bush administration.) Bush’s commerce secretary and former campaign manager, Don Evans, had been the CEO of a Colorado-based oil company and a director of TMBR/Sharp Drilling.

The administration immediately explored rekindling relations with the Taliban, for the simple reason that the Taliban held out the most hope for stabilizing Afghanistan and enabling oil and gas pipelines to pass through the country. But by August 2001, the Taliban was balking at some of the conditions laid down by the Bush administration for moving forward, causing Washington to threaten the Taliban militarily if they did not cooperate: “Either you accept our offer of a carpet of gold,” said US representatives, “or we bury you with a carpet of bombs,” reported the French authors of OBL: The Hidden Truth. Negotiations broke down when, after the 9/11 attacks, the Taliban refused to turn over Osama bin Laden. (Less known is the fact that the Taliban had sought proof that linked bin Laden to 9/11, and the Bush administration refused to supply it.)

It was just a month later, on October 7, 2001, that President Bush ordered the airstrikes against the Taliban, launching Operation Enduring Freedom. Within six months, American troops had soundly defeated the Taliban. Convinced by May 2002 that stability had been restored to the country, the leaders of Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan met to give the go-ahead for a natural gas pipeline, now called TAPI, for the countries it would traverse: Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan—and India, which was invited to join the project. The economic benefits that would accrue to Afghanistan included millions of dollars in transit fees and thousands of jobs so desperately needed in the war-torn country. Reported the BBC, “It is also hoped such a project would boost regional economic ties and pave the way for further foreign investment.” The Asian Development Bank began a feasibility study. Everything seemed to be going to plan. But which plan? Was sending American troops to Afghanistan to avenge 9/11 and fight terrorism (and, little known to most people, to stabilize the country for secure pipeline transit) the makings of “a good war,” as this “war of necessity” had been described? Or was it, as Australian journalist John Pilger declared after the initial relentless US and British bombing campaigns, a fraud? Pilger noted that “not a single terrorist implicated in the attacks on America has been caught or killed in Afghanistan.”

Two New York Times reporters, for their part, saw through the Bush administration’s insistence that oil had nothing to do with the invasion of Afghanistan. In their December 2001 article, “As the War Shifts Alliances, Oil Deals Follow,” Neela Banerjee and Sabrina Tavernise quoted a consultant with Cambridge Energy Research Associates: “Once we bomb the hell out of Afghanistan, we will have to cough up some projects there, and this [Unocal] pipeline is one of them.” Since the 9/11 attacks, the two journalists reported, the United States saw Afghanistan as “a stable oil supplier,” noting that the State Department was “exploring the potential for post-Taliban energy projects in the region, which has more than 6 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves and almost 40 percent of its gas reserves.” Muslims in Afghanistan and beyond, added Banerjee and Tavernise, harbored no illusions about Washington’s ambitions: “Skeptics, especially in the Islamic world, contend that oil interests lie at the heart of the West’s war in Afghanistan.” The authors cited a headline in a Pakistani newspaper as reflecting local sentiment: “The Pipeline of Greed,” read the headline. The accompanying article went on to state, “The war on terrorism may well be a war for resources.” Articles like this tended to be the exception in the West’s coverage of the war. Canadians, however, got a rare dose of reality when, in 2009, a Canadian energy economist named John Foster declared in the Toronto Star that the war in Afghanistan was a pipeline-driven war. Foster quoted a US State Department official revealing the purpose of the pipeline: “Richard Boucher, U.S. assistant secretary of state, said: ‘One of our goals is to stabilize Afghanistan,’ and to link South and Central Asia ‘so that energy can flow to the south.’ Oil and gas have motivated U.S. involvement in the Middle East for decades,” Foster continued. “Unwittingly or wittingly, Canadian forces are supporting American goals.”18 In a scholarly report published earlier, Foster had shown that Canadian forces bore the brunt of the fighting in Kandahar Province along the pipeline route. “The impact of the TAPI pipeline on Canadian Forces must be assessed,” he wrote, “given that the proposed pipeline route traverses the most conflict-ridden areas of Afghanistan, crossing through Kandahar province where Canadian Forces are attempting to provide security and defeat insurgents.”

End of excerpt

The Deadly Politics of the Great Game for Oil

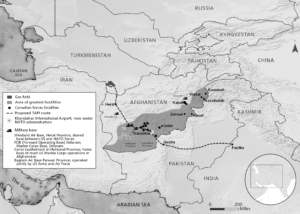

The map above shows the projected route of the TAPI pipeline. Part of the caption reads: “In 2006, Canadian forces were given responsibility for securing Afghanistan’s flashpoint provinces of Helmand and Kandahar, key areas for the proposed TAPI pipeline route, along which major U.S. and NATO military bases are located.”

Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid was one of the first to link the pipeline scheme to the Taliban in his book, The Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia. He discovered that “policy was not being driven by politicians and diplomats, but by the secretive oil companies and intelligence services of the regional states.” Oil companies, Rashid continued, “were the most secretive of all—a legacy of the fierce competition they indulged in around the world. To spell out where they would drill next or which pipeline route they favoured, or even whom they had lunch with an hour earlier, was giving the game away to the enemy—rival oil companies.”

What I call “the deadly politics of the Great Game for Oil” is still going on… in the Mediterranean Sea and the countries that border it (including Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey and Libya). Sadly, in this age of trying to convert to alternative energy to reduce the dangers of climate change, the Great Game is now raging throughout much of Africa. Here is the key to understanding the “endless wars”—that’s plural—that have plagued the war-torn West Asia, Central Asia and now Africa—not just “the forever war in Afghanistan,” as President Biden has chosen to characterize U.S. involvement. My parting advice to all who read this: Just follow the pipelines and you shall find the truth about what drives much of U.S. foreign policy… and that includes the Nord Stream 2 pipeline that will carry Russian natural gas to Germany and beyond, despite the mighty efforts of the United States to stop its completion through sanctions against Russia and companies involved in the project.

Now that a major U.S. pipeline has been cyberattacked, the people of the United States will have a greater awareness of the vital role played by pipelines in energy flows… and the role of “pipeline politics” in directing, protecting—or impeding—that flow, in the United States and overseas.

Charlotte Dennett is a former Middle East reporter and an investigative journalist and attorney. She is the author of The Crash of Flight 3804: A Lost Spy, A Daughter’s Quest, and the Deadly Politics of the Great Game for Oil (Chelsea Green, 2020), a personal narrative and historical investigation into the events leading to the death of her master-spy father, resulting in her discovery of the role of oil and pipelines in today’s endless wars.