Source: Foreign Policy in Focus

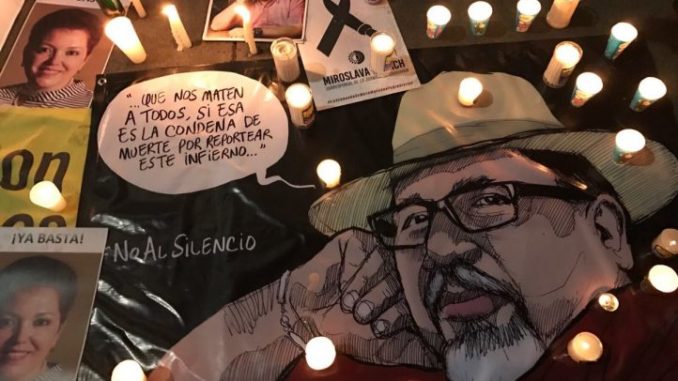

“Let them kill us all, if that is the death sentence for reporting this hell. No to silence.”

That was Mexican journalist Javier Valdez’s defiant reaction to the brutal killing of his journalist colleague Miroslava Breach, who was gunned down in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico this spring.

Less than two months later, on May 15th, Valdez himself was shot and killed in the streets of Culiacán, capital of the northern state of Sinaloa. The state is home to the powerful Sinaloa Cartel, long headed by the legendary Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, now jailed in New York awaiting trial on U.S. charges.

Valdez is the sixth journalist killed in Mexico just this year. According to Reporters Without Borders, Mexico is now the third most dangerous country for reporting, just after Syria and Afghanistan. Shortly before Valdez’s murder, The New York Times reported that since 2000, at least 104 journalists have been killed in Mexico, while another 25 remain disappeared.

Although almost all of the journalists attacked in recent years have been Mexican nationals, the escalation of killings raises questions about the safety of all media workers in Mexico.

Several high-profile journalists have been killed and wounded in conflict zones like Syria, Iraq, and Libya in the past couple of years, but Mexico features a different kind of conflict — less about artillery and aerial bombing, which kill indiscriminately, and more about targeted individuals being “disappeared” or subject to assassination. Still, the death toll in Mexico approaches war-like heights.

A Climate of Impunity

In many cases, human rights advocates say, the journalists targeted were investigating links between criminal syndicates, local politicians, and law enforcement authorities. The sinister connections between government and criminal groups with access to vast amounts of cash has long plagued Mexico and undermined democracy south of the border.

In 2011, Valdez received the International Press Freedom Award from the Committee to Protect Journalists in New York. The prestigious award honors journalists who have done commendable work across the globe. And if a figure as well-known and respected internationally as Javier Valdez could be targeted, it seems, so could any journalist working in Mexico.

Of course, journalists are only a minority of those affected by crime in Mexico. Since 2006, more than 80,000 people have been lost due to violence in the country, according to a 2015 Congressional Research Service report. The situation will only worsen if journalists investigating and reporting on these crimes are silenced.

Human rights groups, such as the Committee to Protect Journalists, have for years been calling on the Mexican government to punish those responsible for the violence. According to a recent article published in The Intercept, the Mexican government’s human rights commission reported that in 2016, 90 percent of crimes against journalists were either unsolved or the perpetrators faced no consequences.

Washington Adds Fuel to the Fire

Meanwhile, the U.S. may be making the problem worse. Washington, after all, is funding the Mexican government’s failing fight against drugs — regardless of the extremely high levels of corruption in Mexico’s security institutions. Often the very policemen investigating these crimes against journalists are involved with the drug cartels themselves.

In June, The New York Times reported that the Mexican government has been using spyware to retrieve private information from human rights lawyers, anti-corruption figures, and journalists through their smartphones — information that some worry could be used to track and target human rights defenders.

But Washington continues to send semi-automatic weapons, helicopters, and armored vehicles, among other amenities to a government in which some sectors appear implicated in an effort to silence the free press. Under a program called the Mérida Initiative, the U.S. has sent more than $2.6 billion worth of this assistance to Mexico, in many cases funding corrupt officials who are often involved in violence against the very people they’re meant to protect.

Adding to the chaotic situation, illegal gun trafficking across the U.S.-Mexico border has supplied both drug cartels and police officials with weaponry to continue human rights abuses.

“A Field Strewn with Explosives”

Unfortunately, not enough is being done to find justice for the lives of so many great journalists lost. Both the U.S. and Mexican governments should be doing more to ensure that journalists’ lives, like those of others, are protected in this violent and lengthy conflict.

The murder of Valdez, a man working tirelessly to expose the inner abuses of drug cartels in Sinaloa, is a tremendous loss for the international human rights community.

Valdez was known for lending a hand to U.S. and other journalists who arrived in Sinaloa to write about Mexico’s drug wars. He was always generous with his time, according to many in the international and Mexican journalist community. At the end of the day, however, the foreign journalists went home. Valdez stayed in Sinaloa, vulnerable to the crime bosses and crooked politicians.

In 2011, Valdez’s acceptance speech for the International Press Freedom Award reflected the unparalleled dangers of working as a journalist in Mexico.

“Where I work, Culiacán, in the state of Sinaloa, Mexico, it is dangerous to be alive, and to do journalism is to walk on an invisible line drawn by the bad guys — who are in drug trafficking and in the government — in a field strewn with explosives,” he said. “This is what most of the country is living through. We, the citizens, are providing the deaths, and the Mexican and U.S. governments, the guns.”

His words still resound today and every day. It’s up to both Washington and Mexico to ensure that Valdez — and human rights defenders like him — doesn’t become just another number in the casualty count.