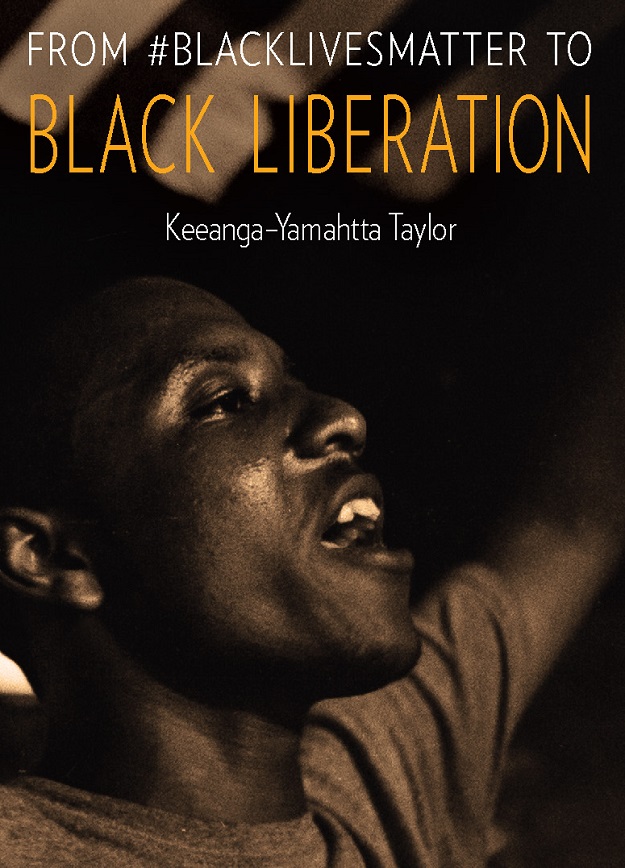

Reviewed: From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor. Haymarket Books, 2016.

How did the Black Lives Matter movement erupt during President Obama’s presidency? Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor successfully answers this question with her book From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation. In seven chapters, she examines the political conditions that led to the Black Lives Matter movement, arguing that Obama’s presidency should be understood as a political continuation of neoliberal capitalism at the expense of working, immigrant, and Black people. In each chapter of the book, she diagnoses racist oppression in the United States from a different angle, and each could stand alone as an independent article. But what is billed as a book pointing the way forward for Black Lives Matter organizers and activists is rather a compelling historical analysis of the lessons and parallels from prior struggles for Black freedom.

This makes the book a disjointed read until the final chapters, where Taylor brings the sum of her analysis to bear on the current Black Lives Matter movement. Instead of offering a strategy to Black Lives Matter organizers to sharpen the struggle for Black Liberation – which she never explicitly defines – she uncovers questions derived from the failed experiments of prior social movements and concludes with an underdeveloped call for interracial working-class solidarity.

Taylor is deft at weaving historical and contemporary analysis of events, and this is effective in building her case that structural racism has been consistently obscured by pathologizing Black culture: “The ‘culture of poverty’ in its original incarnation was viewed as a positive pivot away from ‘biological racism’ rooted in eugenics and adopted by the Nazi regime…This is where liberal and conservative thought converge, however: in seeing Black problems as rooted in Black communities as opposed to seeing them as systemic to American society.”

Taylor emphasizes the consistency of demands across each era of Black struggle, noting that the top three grievances have long been police brutality, unemployment and underemployment, and substandard housing. These issues, she claims, form the historical pattern of Black oppression in the United States.

Presidential commissions produced reports to this effect, while politicians bolstered the welfare state and made concessions to eliminate barriers of access to education and housing. Taylor writes, “The Black freedom movement of the 1960s fed the expansion of the American welfare state and its eventual inclusion of African Americans, Johnson’s War on Poverty and Great Society programs were largely responses to the different phases of the Black movement…the greater emphasis on structural inequality legitimized Black demands for greater inclusion in American affluence.”

From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation builds from there, analyzing the relationship between struggle in the streets and the shifting political economy of race relations in the United States: “The political uprisings of the 1960s, fueled by the Black insurgency, transformed American politics, including Americans’ basic understanding of the relationship between Black poverty and institutional racism – and, for some, capitalism.”

Although she rigorously analyzes the impact of riots on national policy, she only mentions labor struggle briefly, noting that “the struggle over social conditions in their neighborhoods catalyzed their struggles at work. In 1960 there had been thirty-six public-sector strikes. By 1970, that number had grown to 412…During [the period between 1967-1974] there was an average of 5,200 strikes per year, compared with a high of 4,000 strikes in the previous decade.” For a conclusion that calls for building working class power to shut down production, she avoids a thorough historical treatment of Black workers in labor struggles. She characterizes Black militancy in the labor movement as if it came out of militant neighborhood struggles. This ignores the centrality of Black workers in labor actions and strikes dating before the Civil War, and the influence of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters – an all-Black union founded in 1925 – in the formation of the Civil Rights movement.

Despite this omission, her orientation to struggle is dialectical: “Ideas are fluid, but it usually takes political action to set them in motion – and stasis for the retreat to set in.” Taylor contends that politicians and the business class, no longer fearing economic and political instability, developed new rhetoric and policy to erode the gains made in the previous era. These efforts centered on the dubious claim of colorblindness and a narrative of an “even playing field” for all Americans, which cast poverty, violence, unemployment and substandard housing as personal and cultural failures.

One of her strongest points is that winning community control – in the form of Black elected leadership nationally and in cities – did not ameliorate the daily struggle of survival for working class Black families across America. In fact, she argues, the election of Black officials led to systematic recuperation; wherein politically radical demands are absorbed and defused to be used for maintaining the status quo. “The utility of Black elected officials lies in their ability, as members of the community, to scold ordinary Black people in ways that white politicians could never get away with.” Thus, Black politicians were used as tools to substantiate narratives of equal opportunity and color-blindness, meanwhile “[p]ersonal stories of achievement and accomplishment began to replace the narrative of collective struggle.” Taylor’s analysis of the failures of community control, and Black representation in elected office, lead to her elucidation of ongoing questions for the nascent Black Lives Matter movement.

The final chapters of the book coherently link structural racism and class oppression as mutually dependent in maintaining American capitalism – something that in the current political climate is both bracing and evocative.

While Taylor’s introduction poses questions, her final chapters provide succinct answers: “Can there be Black liberation in the United States as this country is currently constituted?” Her answer, simply, is no. “Capitalism is contingent on the absence of freedom … for Black people and anyone else who does not directly benefit from its economic disorder.”

She contextualizes the Black Lives Matter movement as a maturation of the uprisings in cities across the United States in the wake of Mike Brown’s murder in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014. She argues that this movement must enter a new stage that engages “with the social forces that have the capacity to shut down sectors of work and production until our demands to stop police terrorism are met.” Her conclusions are powerful, but she offers no insight into strategy for shutting down work and production. And despite calling for strikes and other workplace actions, she devotes only a few pages to a brief period of militant labor upsurge between 1960-1970.

As a writer of history, Taylor excels. As a strategist for the future, however, she falls short. Certainly the past is prologue, but only so far as its lessons incite change.

####

Avery Pittman is an organizer living in Burlington, VT. They have worked on campaigns to win healthcare reform, stop fossil fuel infrastructure, and build a nontraditional union of downtown workers in Burlington. Currently they focus on anti-fascist organizing in the era of Trump.