by Charlotte Dennett

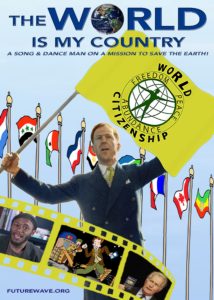

At a moment of unexpected synchronicity, I find myself writing on Earth Day about a pioneer in global consciousness who was best known as “World Citizen # 1.’” He was a former WWII bomber pilot who was so pained about having bombed a civilian city that, in 1948, he gave up his US national citizenship and declared himself a citizen of the world. Many more acts of defiance would follow, landing him in prison 34 times. Now, the late Garry Davis (1921-2013), whose obituary appeared on the front page of the New York Times, is the subject of a newly released documentary by Arthur Kanegis and Melanie N. Bennett called The World is My Country. It is now airing on public television stations across the country — including Vermont broadcasts on May 2.

Actor Martin Sheen opens the film with an impassioned introduction. Garry Davis, he says, is “an actor, a song and dance man, who lept off the Broadway stage onto a world stage in 1948.” We see clips from his life as Sheen describes Davis “taking on cops, bodyguards, armies and whole nations, showing us that we don’t have to accept a world ravaged by war, plunging into environmental disaster.”

Sheen then beckons a spry 91-year-old Davis onto a stage before a cheering crowd in Burlington, Vermont.

It was to be his last performance. He was dying of cancer. The actor in him unabashedly reveled in the attention. “I am very appreciative that you are here as an audience and I am here to entertain you,” he says. “So what do I need this cane for?” He laughs (as he often does), throws away his cane and starts to tap dance. The crowd loves it.

There was always a prankster and comedian in Garry Davis. He had a genius for getting attention, most often from those in authority who would not otherwise give it. But his mission was deadly serious.

As I watched his many, mostly solitary acts of rebellion against authority in this film, I started making mental comparisons to the young climate activist, Greta Thunberg.

Neither Greta nor Garry minced words. Both condemned world leaders for threatening humanity’s survival. Her issue was – and is – the scourge of climate change; his issue was the indefensibility of “waging world war over artificial borders.” And, ironically, both turned to the United Nations to make their most famous statements. Greta did so in her famous “How Dare You?” speech to the UN climate action summit meeting in New York in 2019; Davis made his famous “I interrupt” speech to the UN General Assembly which was meeting in Paris in 1948.

“I INTERRUPT in the name of people not represented here!” he shouts from the balcony. Pandemonium breaks out. Above the din, he continues, “The nations you represent divide us and lead us into the abyss of total war. What we need is one government for one world. And if you won’t do it, step aside and a people’s world assembly will arise from our own ranks to do it.”

He is hustled away while his speech is translated into French. His action explodes into headlines around the world.

The Garry Davis Spectaculars

This was not Garry’s first spectacle that year, nor the last. It had followed a crescendo of popular support – all captured with historical footage in the film — that began, weeks earlier, when he officially surrendered his American citizenship. Standing before a French consular officer, he turned in his US passport and declared himself a world citizen. “There’s no such thing,” the consul replied. “There is now!” Garry retorted. Now stateless with no documents (the situation of refugees around the world, he reminds us in the film) he next staged a six-day sit-in at the UN’s temporary headquarters in Paris, deemed international territory for three months. His sit-in “caused a clamor,” he narrates. “Europe was still in ruins and people were so fed up with war.”

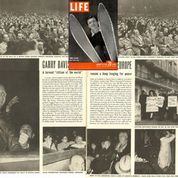

He made international news; some of France’s leading French intellectuals took notice, including Jean Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Simone de Beauvoir. They formed a committee of support, helped him stage his “I interrupt” protest, and then held a huge rally in the Velodrome D’Hiver, the equivalent of New York’s Madison Square Garden. Twenty thousand people packed the room and cheered him on. A heady experience to be sure, featured in a big spread in Life Magazine.

An international movement grew up almost overnight. Shortly after “I interrupt,” the General Assembly unanimously adopted the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Its author, Eleanor Roosevelt, wrote in her newsletter “how much better it would be if Mr. Davis would set up his own governmental organization [because the UN was not a governing body, she conceded] and start then and there a worldwide international government.”

It was a daunting challenge, but over the next two years, Davis and his French compatriots registered 750,000 people as world citizens. These early historic events would eventually lead to his formation of a World Service Authority headquartered in Washington, DC which would issue world citizen passports and identity cards to hundreds of thousands of people.

The filmmakers’ mission

Remarkably, most of Garry’s episodes are captured by archival footage, discovered by Arthur Kanegis and the filmmaking team — and deftly edited into the film along with eyewitness interviews and more. Complementing the creative team of Kanegis and Bennett was Marc Hughes, Garry’s “cartoon biographer.” His cartoons provide comedic breaks but also serious insights.

The overall result: A stunning documentary, a David v. Goliath story that both educates and entertains while preparing us to think that we might just be able to change the world.

Kanegis is the son of Quakers and an independent filmmaker who has dedicated himself, he told me, to “a lifelong mission for peace.” He produced films to stop the Vietnam war. He did research on the historic anti-nuclear film, The Day After. He eventually concluded that there were “all these movements about all the things we’re against, but no one had a good integrated vision of what we’re for.” He started to develop a movie about a “fictional future with futuristic peacekeepers working on behalf of a global democracy,” but then read Garry’s book, My Country is the World. “It was so filled with action and drama that I just had to make a movie of it!”

Once he bought Davis’ story rights, it took Kanegis a challenging two decades to raise funds and put the film together. He started out planning to make a narrative feature – with a top comedy actor playing Garry — but due to budget constraints he shifted to making a documentary. “In our early interviews Garry would go off on tangents talking about his ideas for the world and his philosophy, never getting to his amazing story.” Finally, Kanegis woke up one morning with an epiphany: Garry’s an actor. Let’s bring him back on stage! Garry was thrilled by the idea and was equally thrilled that his message would carry on, even when he was gone.

Kanegis ended up making a documentary with a story so riveting that it has the feel of a narrative feature. We meet Davis in his formative years through home movies. He was the son of the famous society band leader Meyer Davis, who, Garry recounts, “played at nine presidential inaugural balls from Harding to Ford.” Garry aspired to be a famous actor on Broadway, and came close when he got 13 curtain calls the one night he stood in for Danny Kaye in a Broadway play.

That all changed when two searing experiences affected him during World War II: One was the death of his beloved brother and mentor, Buddy, then serving in the US Navy when his boat was “blown to bits” near Salerno, Italy. The second was when Garry, as a B-17 fighter pilot, bombed Brandenberg, Germany, only to later see films of the horrific damage he had wrought. These two personal experiences, plus horrific scenes of human suffering after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, got Garry started on a lifelong quest: How to end what he believed was “the most irrational enemy of all, war itself.”

Garry’s Vermont Connections

Burlington was his home for 23 years and (full disclosure) my home as well, where I got to know Garry through his girlfriend and my close friend, filmmaker and peace activist Robin Lloyd. It was, in fact, Robin’s grandmother, Lola Maverick Lloyd — who sailed to Europe in a boat full of concerned women in an effort to stop World War I and later helped found the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF)– which accounts for Robin’s meeting Davis in 1990. He knew about Lola’s campaign for a world government to stop war when he came through town on his way to see family in nearby Montreal. And Robin knew about him and his crusade. Their budding relationship seems, in retrospect, inevitable. In 1992, Robin would profile him and his World Service Authority (which, by then, had issued 250,000 passports to stateless persons and refugees) in her film, Passport to Freedom. She is an executive producer of The World is My Country and provided footage and funding to complete the effort.

My husband, Jerry Colby, and I had many wonderful conversations with Garry. We featured him several times on our Channel 15 TV show, Where Do You Stand? and visited the World Service Authority in DC. We wanted to see for ourselves, having been aware of Garry’s critics and naysayers. Garry was used to people calling him crazy. He says in the film: “On September 4th 1953, I declare, at the City Hall of Ellsworth Maine, a government of, by and for the people of the world! You say this is crazy, but I did it!” Crazy, but how many of his critics could boast of an endorsement from Albert Einstein, or praise from famous French intellectuals like Albert Camus, or encouragement from Eleanor Roosevelt?

At the WSA headquarters, we saw the hundreds of photos of world citizens and letters thanking him for their passports. We met with human rights attorney David Gallup, who heads up the World Service Authority, continuing the work he did with Garry over the decades. Today, he reports that WSA has issued almost 5 million World Documents since 1954, including World Passports, Birth Certificates, ID Cards, World Citizen Certificates, Marriage Certificates, Political Asylum Cards, and other human right documents — all mandated by clauses in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The WSA website displays copies of Visas stamped in World Passports by 188 nations (of the 193 in the UN). (WorldService.org – click on VISAS). However today it is very difficult to use it as a travel document. The full 83 minute documentary tells the story of Yasin Bey (Mos Def) who says “My country is called Earth” — but when he tried to leave South Africa using only his World Passport he ended up getting detained. Nevertheless these documents have proven to be lifesavers for many of the 50 million stateless people in the world, serving as identity documents to get their kids into school, get medical care, to get into a courthouse to have their asylum cases heard and so much more. See TheWorldIsMyCountry.com/passport.

More Vermont Friends and Collaborators

Garry’s friendship with Vermont cartoonist Marc Hughes started in 1990, when Garry took up residence in Vermont. Soon Marc was illustrating many of Garry’s World Citizen newsletters, trying – at Garry’s insistence — to simplify complex ideas “into fewer words and images.” In the film, he succeeds.

Toward the end of his life, Davis also collaborated extensively with Burlington attorney Mark Oettinger, who specializes in public and private international law. Oettinger became inspired with Garry’s determination to bring about World Law. At Garry’s urging, Oettinger put together a team to draft a statute for a World Court for Human Rights, a topic which has been under discussion since 1947, the year before the United Nations’ passage of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Like Garry before him, Oettinger traveled to Lucknow, India where the world’s chief justices assemble every year. There, he received the chief justices’ unanimous approval of the statute, which is also known as the Treaty of Lucknow. Oettinger has since presented the Treaty to the American and Canadian Bar Associations, and is currently seeking sponsors to help incubate debate and adopt the Treaty through the United Nations treaty accession process. More information on the Treaty, and the history of the project, can be found at www.worldcourtofhumanrights.net.

All told, I found this film to be beautifully wrought and indeed prescient, especially when Davis’s vision of a “global room”– where citizens could conduct their governmental affairs without violence — actually came true with the introduction of Zoom to our pandemic lives.

President Biden’s virtual climate summit on Earth Day, challenging 40 world leaders to take a stand in public, may, we have to hope, be a sign of progress.

Garry felt a great sense of peace knowing that this film would one day come out. He didn’t live to witness the pandemic, or the border crisis with Mexico with its thousands of desperate migrants seeking refuge in the US, or the horrific storms and fires that have swept through this country and destroyed many parts of the world in recent years. Nor did he live to see this film playing on PBS affiliates across the country. He would have applauded the emergence of the Black Lives Matter and MeToo movements. He strongly believed women would play a major role in changing world consciousness, convinced of the dangers of nuclear annihilation and futility of endless wars that killed their children. But my final thought is this: Albert Einstein, back in 1949, commended Garry for “having grasped the only problem..to which I am determined to devote the rest of my life: whether mankind…will disappear by its own hand or whether it will continue to exist.” Today, 72 years later, Einstein’s question has an even greater urgency, and we have Garry Davis to thank for sharing his vision of a better world and charting a course in which one day, hopefully before it’s too late, we can all be World Citizens living in a safer, cleaner, and more harmonious world.

As a snappy song by Jahcoustix feat. Shaggy closes out the film: “Out of many we are one. We are world citizens, … for equal rights and justice. … what’s happening, to this beautiful world that we’re living in? World citizens, lift up your voices .. all we need is the same direction headed in one way … People arise! Let them hear you! I know we can change it because the time has come. …The same direction, many connections. We are one.”

Charlotte Dennett is an author, investigative journalist and attorney. For the past six months she has served as guest editor for Toward Freedom. Her newest book is The Crash of Flight 3804: A Lost Spy, A Daughter’s Quest, and the Deadly Politics of the Great Game for Oil, a personal narrative and historical investigation into the events leading to the death of her master-spy father, resulting in her discovery of the role of oil and pipelines in today’s endless wars. She identifies as a world citizen.

The 58 minute TV version of the movie is playing on Public Television Stations across the country. In Vermont it is playing May 2 at 5 PM on several channels. You can see the local broadcast times, stations, and channels by clicking on Public TV at TheWorldIsMyCountry.com

To watch the full 83 minute feature-length movie click on the store tab at that same website.