by Nikola Mikovic

Just over a year ago, Russian President Vladimir Putin, appearing against a blaze of national flags representing 40 African countries, addressed a large audience of heads of states and government officials in Sochi, Russia. He was presiding over the first-ever Russian-African summit. It was a seminal event, one that “opened a new page in relations between Russia and the states of African nations,” Putin declared.

One of the most talked-about outcomes of this summit was Moscow’s plans to establish a long-sought military base in the strategically- located East African country of Sudan, giving Russia’s navy a permanent gateway to the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean.

A year later, on November 16, 2020, Putin authorized his Ministry of Defense to sign the formal agreement with Sudan to create the permanent Russian military base in Sudan, guaranteeing Russia’s first substantial military foothold in Africa since the fall of the Soviet Union. In a continent which is fast becoming the new focus of East-West rivalry for control of its abundant natural resources–chief among them oil—observers are assessing Russia’s motives. What lies behind Moscow’s decision to open a naval base in Sudan? And how has Russia’s chief adversaries in the great game for oil – the United States and its allies – responded?

The base, officially described as a material-technical support facility, is likely to open up new opportunities for Russia to expand its military and political influence in East and Central Africa. The base will be able to berth up to four warships, including nuclear-powered vessels. The location of the new naval facility, which will be capable of accommodating up to 300 military and civilian personnel, will be close to the main Sudanese trading port on the Red Sea—Port Sudan.

Sudan has reportedly been the second largest African buyer of Russian weapons for the past 20 years, and in 2018 the trade between Russia and Sudan reached $510 million.

Soviet advances in Africa during and after the Cold War

At the Sochi summit, Putin was quick to remind his audience of Russia’s opposition to “colonialism, racism and apartheid” during the Soviet era, and Russian support for the African nations’ struggle for independence.

Moscow made significant investments in the region, and during the Cold War it established strong military-political positions in Africa. The Soviet Navy has been present in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean (albeit without a military base) since 1964. Also, the ships of the USSR Navy periodically stopped at various material-technical support facilities in Angola, Guinea, Tunisia and Ethiopia. Following a 1972 agreement between Somalia and the USSR, Somalia’s Berbera Port’s facilities, located on the Sea of Aden just below the Red Sea, were patronized by the Soviets. The port was later expanded for US military use after the Somali authorities strengthened ties with the American government in the 1980s. After the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia’s presence in the continent sharply declined. However, Africa seems to be on Moscow’s active radar again.

Russia’s Comeback

Since 2016, Moscow negotiated the free entry of its ships to ports of nations such as Sudan, Eritrea, Egypt, Mozambique and Libya. There is speculation that Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, the current leader of the Libyan National Army (LNA) who visited Russia in July of 2016, offered Russia the use of the Eastern Libyan port of Benghazi as a full-fledged naval base in exchange for arms supplies. According to a subsequent (September, 2016) report by the Brookings Institute on Russian-Libyan relations, “Russia was in search of strategic bases on the Mediterranean,” and Gadhafi, before his overthrow, had “granted Moscow access to the port of Benghazi for its fleet.” Although Russia still does not have any military facilities in Libya, Turkish media claim that Moscow aims to create a base on the Mediterranean in this oil-rich North African country. The Russian private military contractor, The Wagner Group, already has up to 1,200 people deployed in Libya to strengthen Haftar’s forces, according to a UN report leaked to Reuters in May, 2020. The United States, on the other hand, officially “has no role” in Libya, while its NATO allies are divided over the support of their proxies on the ground. France and Greece, for instance, strongly support Haftar, while Turkey and Italy back the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) based in Tripoli.

Energy and arms trade appear to be the main reasons for Russia’s involvement in Libya’s conflict. Before 2011, and the NATO-instigated fall of the Qaddafi regime. Moscow and Tripoli had deals guaranteeing the supply of Russian equipment and weapons to Libya, and the Russian oil and gas companies Lukoil, Tatneft and Gazprom signed several agreements with the then-Libyan authorities. Since 2014, the Russian energy giants have had to suspend their operations while the civil war ripped apart the country, although recently Tatneft resumed seismic acquisition activities in the Hamada basin, located in the northwestern part of the country. Besides oil, the Kremlin’s interests in this part of the world are motivated by the flow of natural gas. It is believed that Moscow aims to prevent Turkey from implementing a maritime border delineation deal with Libya which would allow Ankara to extract natural gas directly from the Mediterranean Sea, instead of buying it from Moscow. Thus, natural gas is one of the key reasons why Russia and Turkey are involved in the civil war in Libya, a crucial Mediterranean country.

Russia’s base in Syria

Presently, Russia has just one navy base in the Mediterranean. It is located in Syria – another country that has been consumed by civil war, a conflict which soon degenerated into proxy wars pitting the Assad regime and his Russian and Iranian defenders against the US and its NATO and Gulf state allies, primarily Qatar and the United Arab emirates.

The port of Tartus serves as the Russian Navy’s repair and replenishment facility and is currently undergoing major renovations and expansion. Assad, with Russian help, has regained control over most of Syria, with Tartus playing an important role in basing Russian troops involved in the Syrian war.

Turkey has also contributed to Russia’s involvement in Syria, allowing Russia to use Turkish territorial waters to supply its troops in Syria. The fact that Russian ships on their way from the Black Sea to Syria have had to pass through the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits – effectively controlled by NATO member Turkey – suggests that the Russian intervention in Syria is part of a broader strategic understanding between the Kremlin and one of its “dear Western partners,” (a phrase Putin and his foreign minister Sergey Lavrov are fond of using on a regular basis.) Otherwise, Turkey would have closed the straits for Russian vessels a long time ago.

The Sudanese Energy Factor

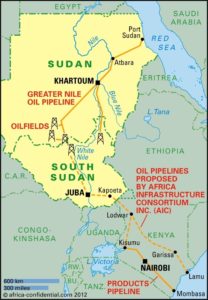

Since the United States and its Gulf allies have not officially opposed Russia’s plan to build a base in Sudan, such a decision is likely part of another tacit deal between foreign actors. Russia’s new military foothold in Sudan will be considerably smaller than its naval base in Syria’s Tartus, but the base is likely to help Moscow establish control over the transit flows of oil that pass via pipelines through the region. The bulk of local oil fields are located in neighboring South Sudan, but its oil exports are almost entirely dependent on the Republic of Sudan. The only pipeline through which landlocked South Sudan can transport its energy passes through the territory of Sudan, its northern neighbor.

Port Sudan is a fairly large facility that provides important access to the Red Sea, not only for South Sudan, but also other for regional neighboring land-locked countries such as Ethiopia and Chad. In April, Sudan’s transitional government took steps to hand over control of its principal seaport to the United Arab Emirates, a staunch ally of the US and Israel.

It is worth remembering that after the overthrow of the Sudanese leader Omar al-Bashir in 2019, the UAE and Saudi Arabia announced a $3 billion aid package to stabilize the situation in the country. Even though Moscow managed to consolidate its position in the region by signing long-term agreements with Sudan’s authorities, it will now have to find a way to avoid direct confrontation with the interests of the Gulf monarchies in the northeast African country.

The Red Sea, according to a series on its growing importance by Africa Report, has become a “magnet for outside powers vying for its control.” While it is clear that freedom of naviagtion through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal is goal shared by all, tense regional dynamics not only in Sudan, but also Ethiopia, Somalia and Yemen augur an era of ongoing instability in this heavily contested region.

Russian leaders clearly realize all the challenges the Kremlin faces in East Africa at a time when the United States, China, Japan, India, Turkey, France, South Africa, and the European Union are all vying for influence. Vladimir Putin’s hosting the Russia Africa summit last year in Sochi signifies Moscow’s interest in becoming a major player in the continent. It is widely believed that Putin’s achievement in securing the military facility in Sudan is just the first step in Russia’s return to Africa. A Novembor 19th story in Russia’s RBK TV, entitled “Why Russia needs a military facility in the Red Sea,” explores at length the significance of this development, drawing in part from an interview with Viktor Murakhovsky, a Russian military expert and editor-in-chief of Arsenal Otechestvo (translated, National Arsenal). RBK chronicles the development of the Russian Military-Industrial Complex, the armed forces and law enforcement agencies of the Russian Federation. Murakhovsky was quoted as saying that once the base is opened, “Russia will secure its control over the route through the Suez Canal, through which carries about 10 percent of all world shipping.” At the same time, the defense expert anticipated Sudan’s recent normalization of ties with Israel, which meant that “the field for rivalry with Washington is expanding, as the new [Biden] administration is set to actively work with the Sudan.” Even so, he noted that Russia’s new base on the Red Sea will mean Russia’s maritime activities in the region will extend southward far beyond Sudan, ensuring “ a permanent presence in the Indian Ocean,” which was lost in the post-Soviet years.

Nikola Mikovic is a contributor to CGTN, Global Comment, Byline Times, Informed Comment, and World Geostrategic Insights. He is a goepolitical analyst for KJ Reports, and Global Wonks

.