By Eric Agnero

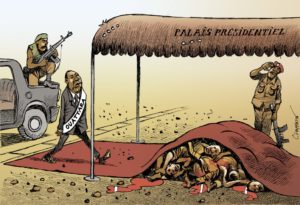

It should have been a democratic success story. The presidential election in Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa in October 2020 was expected to put an end to three decades of political unrest with the first peaceful transfer of power. Instead, though the constitution says the president can only stay in power for two terms, Alassane Ouattara ran for and won a third presidential term amid ethnic violence, extreme police brutality and the jailing of his opponent, thus barging his way to a presidency for life. Ouattara (79) turned his back to a constitutional tradition that has been growing strong roots since the 1990s, limiting the number of presidential terms to two in most of West Africa’s countries. He went along with an alarming political epidemic, popularly known as a “constitutional coup.” The US-educated, hopeful “democracy champion” endorsed by President Barack Obama in 2010 has turned into a deceitful tyrant.

By accepting this democratic backsliding, it would appear that the Obama administration, and then the Trump administration, decided to join Côte d’Ivoire’s former colonial master, France, in securing the loyalty of local puppets in the regional competition against China, Russia and other emerging powers. At stake: the control of natural resources and the establishment of an enlarged military presence. In short, the new scramble for Africa.

“By condoning Ouattara’s dictatorship, we feel like America has ignored the call of the Ivorians to breathe the oxygen of democracy,” regrets an Ivorian pro-democracy activist, and instead, “has agreed to help France keep its knee on ourthroats.’’ Will President Joe Biden also look the other way?

Beheaded for saying no to the third term

In a gruesome video authenticated by French TV, France 24, pro-Government militia members are seen holding machetes and playing in a soccer-like game with the head of a young member of the opposition whose decapitated body is bathed in a pool of blood. The scene took place on November 9, 2020, in Côte d’Ivoire during a protest by the opposition. The demonstrators were denouncing what they called an illegal and unconstitutional third term re-election of President Ouattara. The beheading was seen by many observers as highly provocative, geared to deepen tribal and religious divisions between pro-government and pro-opposition supporters. It could also be the foretelling of a xenophobic bloodbath in the West African ex-French colony, with a potential escalation into a region already facing an increase in destabilization.

A few weeks before the 2020 presidential election, on August 18, Amnesty International alerted the world that Ouattara’s police were allowing machete-wielding men to attack protesters. Then, on August 25, 2020, a U.S. embassy brief urged Alassane Ouattara’s Ivorian security forces to respect and safeguard the rights of all citizens, including those who participated in peaceful demonstrations. In September 2020, the European Union also urged the government to guarantee fair and transparent elections in follow up to the deliberations of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (AfCJHR) ordering the country to suspend its arrest warrant for dissident leader Guillaume Soro. The same court ruled a few years earlier that the Ivorian Electoral board was partisan and violated international norms. In reaction, President Ouattara rejected the rulings and withdrew Cote d’Ivoire from the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, saying the court had undermined its sovereignty.

Considering the unfair electoral context of an unconstitutional third term, the opposition called for a general boycott on October 15, 2020, which was largely followed by the populace. It left Ouattara virtually running against himself. The result was “a non-inclusive and boycotted ballot that leaves a fractured country,” noted the International Election Observation Mission, led by a South African NGO (the Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa) and the Carter Center.

The outbreaks of violence surrounding the latest “constitutional coup” in Côte d’Ivoire has claimed at least 80 lives and made more than 3,000 people flee the country.

“Unfortunately, it was a decision [to seek a third term] I had to assume,” Ouattara explained to CNN on December I4, 2020. “I didn’t plan to run, but when my chosen successor died unexpectedly [on July 8,2020] I had no choice. It’s a decision I am glad I took today because the country would have been in a mess if I had not been a candidate.”

Ouattara the insider

Alassane Ouattara appeared for the very first time on Côte d’Ivoire’s political landscape in the early nineties. The economy was in dire straits. A three-decade-old economic boom came to a halt due to a number of reasons: the increase in pressure on the land; the fall in agricultural prices and the crisis in the plantation economy; the fiscal crisis and the reduction in public resources; and the pressure from the streets, carried by the democratic wind blowing from the East.

In April 1990, Ouattara was a functionary for The Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO), a central bank that serves eight former West African French colonies. The bank imposed bitter remedies on the country, prescribed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Most notably was a savage privatization policy, conducted under the infamous Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs). SAPs are economic policies for developing countries that have been promoted by the World Bank and the IMF since the early 1980s. They provide loans conditional on increased privatization, liberalizing trade and foreign investment, and the balancing of government deficits. Such policies are often criticized for dismembering the social sectors in these countries.

In October 1990, Ouattara was appointed the all-powerful Prime Minister of Côte d’Ivoire by the ill and incapacitated old father of the nation, President Félix Houphouet-Boigny. In 1993, the ailing Houphouet-Boigny died. This triggered a power struggle between Ouattara and Konan Bédié, the constitutional successor to the presidency. Ouattara was pressured to back down in order for the rule of law to prevail. The former prime minister went back to the IMF as Deputy Director in charge of Africa.

Ouattara, who held citizenship in the neighboring Burkina Faso, has always been at the heart of a divisive debate on ethnicity. In 2002, a group of rebels who made neighboring Burkina Faso their rear-base, took control of the Northern Ivory Coast after a failed coup against then-President Laurent Gbagbo. The rebels’ primary grievance was ” the marginalization of northerners within — and exclusion from — the political process, most notably concerning the repeated denial of candidate eligibility rights to Ouattara, the most prominent politician of northern ethnic origins,’’ explained Nicolas Cook, a specialist in African Affairs, in a Research Service Report for Congress, on January 28, 2011.

Decades of violent electoral battles

Côte d’Ivoire has been dealing with recurrent electoral tensions since the death of its first President Félix Houphouët-Boigny in 1993.

In 2010, a previous presidential election was set to seal the reunification of the Ivory Coast, which had been partitioned in 1999 by a military coup and the civil war that followed. The partition resulted in a pro-Ouattara, rebellion-controlled North, and a democratic, government-controlled South. On November 28, 2010, a runoff vote between the incumbent president Laurent Gbagbo and former Prime Minister Alassane Ouattara ended in a deadly stalemate.

The 2010 Electoral Commission declared Ouattara the winner. The result was backed by a UN certification and the endorsement of the international community, including the United States. The highest Court overturned that result, arguing massive fraud, and ruled that the incumbent, Laurent Gbagbo, had won. Despite mounting pressures from Washington and sanctions from the European Union, Gbagbo refused to cede power. To resolve the deadly standoff, Gbagbo proposed an international commission to verify the election results, with the pre-condition that both he and Ouattara should accept the determination of the commission. The international community rejected the proposal.

At the height of the 2010 post-electoral crisis, on March 15, 2011, in a video message to a divided Ivorian population, President Obama endorsed Ouattara as “a needed leader that would bring hope, peace, reconciliation and the restoration of the country’s rightful place in the world.”

Two weeks later, a military action by Ouattara militia fighters designed to oust the clinging Laurent Gbagbo was marked by what is referred to as the “Massacre of Duekoue.’‘ The militias summarily executed hundreds and raped people perceived as Gbagbo supporters in their homes, as they worked in the fields, as they fled, or as they tried to hide in the bush between March 28 to 29, 2011, reported Human Right Watch.

After days of airstrikes by French and UN helicopters and the alleged use of US-supplied incapacitating gas on the presidential palace, French soldiers were able on April 11, 2011, to break the resistance of the last forces loyal to the incumbent president. It is not clear how he was captured. But according to Gbagbo, French soldiers stormed his palace. They captured him and his wife and handed them over to Ouattara’s militia members. France admits its forces played a part in the operation to unseat Laurent Gbagbo, but denies its troops made the arrest.

Allegations of crimes against humanity committed during the 2010/2011 post-electoral violence in Côte d’Ivoire were brought before the International Criminal Court, which in 2019 ended up acquitting Laurent Gbagbo of all charges. Since his acquittal, several questions remain: If not Gbagbo, then who is to blame for thousands of reported deaths during the power struggle episode of 2010? When, many Ivorians wonder, will the pro-Ouattara militias, accused of horrendous war crimes such as the ” Massacre of Duekoue,” going to be tried?

A good yet embarrassing tyrannical friend

President Barak Obama’s enthusiastic promises to the Ivorians turned out to be empty words. Instead of ushering in the ”time for democracy ” that would bring shared prosperity to millions of people, the last ten years have left nothing but a bloody trail of continued violence in impoverished and divided communities, according to pro-democracy activist Dr Becanty Kouadio. “Beyond the flattering claim of economic success,” he says, “lies a national tragedy that goes unnoticed or ignored.

Absolute power–and the control of the 3 branches of a government plagued by tribal corruption and cronyism — has Ivorians comparing the reign of President Oattara to the French emperor Louis XIV, who famously said: ” l’Etat c’est moi (The state is me).

The Ivorian government has regularly been accused of muzzling political dissidence and crushing peaceful protests with absolute impunity. Freedom House, a U.S.-based, U.S. government-funded NGO that conducts research and advocacy on democracy, political freedom, and human rights, in its latest country report shows Côte d’Ivoire to be a far cry from the land promised by Barak Obama 10 years ago. Similarly, the US State Department’s latest annual Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Côte d’Ivoire lays out a litany of “significant human rights issues including arbitrary killings by police.” Nonetheless, the West generally lets off easy the Ivorian President.

According to Dr. Pascal Kokara, a Georgetown University Emeritus Professor and a former Côte d’Ivoire Ambassador to the US, this still-condoning attitude by Western powers towards Ouattara likely has its roots in a widespread narrative that its Islamic population constitutes a near majority in the country. From this premise follows the false argument that President Ouattara may have the majority of the vote, even though he is a despot. “The country is far from being at peace,” warns Kokora. The real danger, he adds, comes from ”President Ouattara’s stirring up of ethnic conflicts and the rhetoric and policies that have led to deep ethnic divides and violence in a country that used to be a beacon of peace and ethnic cohesion in the West Africa region.”

A threat to regional stability

An “obligé” of France, more than a US ”asset’’ in the region, Ouattara is nonetheless considered by many of his opponents as “an economic hitman.” Seen as a former agent of the IMF and an “insider,” he has been able to play around French/U.S foreign policy agreements that advocate for the promotion of stability in Francophone Africa. The continued presidency of Ouattara is seen to be in the best interests of both countries.

For Professor Kokora, France, the former colonial ruler, has had important economic ties to the Ivory Coast and has much to lose if or when a president does not heavily support their exclusive interests.

As for the U.S., the-looking-the-other-way policy when it comes to what Donald Trump infamously described as ‘”shithole countries” seems to be deeply rooted in a long history of racially biased foreign policy standards applied to sub-Saharan Africa, reflective of American racist policies within its borders. In this way, France has been free to keep its former African colonies under political, economic and cultural domination, while pillaging their economies through its support of corrupt and docile dictators. Among its former colonies so affected are the Ivory Coast, Senegal and the world’s largest Uranium producer, Niger.

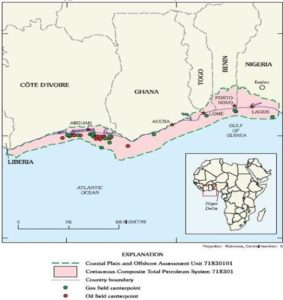

Bottom line: as long as the U.S. gets its share of crude oil in a region that has emerged as a global hot spot, and secures, among other resources, its long-term supply of cocoa labor, it will turn a blind eye to France’s ongoing abuse of power.

This obsession for peace at any cost in Africa seems to be motivated by fear of the recurrence of atrocities such as those of the Rwanda Genocide and the subsequent Great Lakes refugee crisis. The notorious U.S. and French rivalry in the region blinded the two UN security council members into missing countless opportunities to mitigate, if not prevent, a conflict that has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands people, notably more than 800,000 Rwandans in a month. Since then, the two western allies have decided to enhance their diplomatic and military cooperation, especially in West Africa. However, as the Great Game for Oil is now on steroids in Africa, the “peace at any cost” may also have something to do not just about fear of more atrocities, but rather the fear such atrocities may pose to Western banks and oil companies. In other words, stability will be disrupted and financing will not follow.

As in many other sectors such as finance, transport, logistics and utilities, the French dominate oil production in Côte d’Ivoire, and receive most of its licenses. To repeat, what France and the U.S. want is stability so they may readily exploit the country of its resources. This is why there has been a substantial military buildup in Africa through the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM). According to the U.S. Department of Defense, AFRICOM aims to promote and protect U.S. strategic objectives in the region with a mandate to conduct military operations — if so directed by U.S. national command authorities — in line with the State Department’s overall direction. Ron Meyers, the Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (DASD) for African Affairs, puts it this way:

“We probably sometimes forget the outsized role that African partners or African countries play in not only global affairs, but in the world economy. If the European and Asian nations are investing more on the continent, maybe we should be asking what they see, that we should see.”

However, the democratic shortcuts – i.e., rigged elections in the region and the atmosphere of ethnic divisions and the violence they foster — are

ploughing the furrows of larger destabilization. The recent surge of “low-intensity” conflicts in West Africa, even within notably stable countries such as Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal, could be signs of growing political incertitude.

These conflicts often have sprung amid “constitutional coups,” disputed elections, bad governance and corruption, human rights violations and ethnic marginalization. The recent killing by rebels of Chad’s president, Idriss Deby, who was a key Western ally in the fight against Islamist militants in Africa, is a reminder of how fragile stability at the cost of democracy could be. While the U.S. State Department said that the U.S. supports a “peaceful transition of power in accordance with the Chadian constitution.” the commander of AFRICOM, General Steven Townsend, seemed reassured by the fact that Deby’s son is inclined toward good relations both with France, which has a military base in Chad, and the United States.

Mahamat Deby replaced his father,Idriss, even though the constitution stipulates that the president of the national assembly is first in line to take over when a president dies. This unconstitutional transfer of power, along with family divisions, rivalries in the military and the rebels’ menace to overthrow the new leader cast deep uncertainties for the country and a wider region where the US military is already operational.

The rise of jihadist movements in West Africa, including Boko Haram, begs the question: Cui bono, who benefits? For decades the world’s superpowers have used their “wars on terror” as a pretext for sending troops to protect African citizens from terrorists. In so doing, they are disguising their real intent: to dominate and safeguard the riches of Africa. The Chadian imbroglio is just the latest example of how political chaos could play right into the hands of ISIS and Al-Qaeda representatives in the region, resulting in more militarization by AFRICOM, and more protection of resources deemed vital to AFRICOM’s Western backers.

.

.