By Mathew Cole

This major investigative article was originally published in The Intercept

IN 2019, Erik Prince, the founder of the notorious mercenary firm Blackwater and a prominent Donald Trump supporter, aided a plot to move U.S.-made attack helicopters, weapons, and other military equipment from Jordan to a renegade commander fighting for control of war-torn Libya. A team of mercenaries planned to use the aircraft to help the commander, Khalifa Hifter, a U.S. citizen and former CIA asset, defeat Libya’s U.N.-recognized and U.S.-backed government. While the U.N. has alleged that Prince helped facilitate the mercenary effort, sources with knowledge of the chain of events, as well as documents obtained by The Intercept, reveal new details about the scheme as well as Prince’s yearslong campaign to support Hifter in his bid to take power in Libya.

The mission to back Hifter ultimately failed, but a confidential U.N. report issued in February and first reported by the New York Times concluded that Prince, a former Navy SEAL, and his associates violated the U.N. arms embargo for Libya. For more than a year, The Intercept has been investigating the failed mercenary effort, dubbed Project Opus. This account is based on dozens of interviews, including with people involved in the ill-fated mission, as well as the U.N. report and other documents obtained exclusively by The Intercept. It includes a blow-by-blow account of how Prince and an associate sought to pressure the Jordanian government to aid the illicit mission, as well as previously unreported details about how the architects of Project Opus used Prince’s connections to the Trump administration to try to win support for their efforts in Libya.

The Intercept’s reporting shows that the push to aid Hifter continued even after Project Opus fell apart. In the summer of 2019, after their backdoor efforts failed to convince Jordan to approve the arms transfer, Prince called a member of Trump’s National Security Council to request a meeting; Prince asked the official to meet with Christiaan Durrant, Prince’s business associate and former employee. At the Army and Navy Club near the White House, with Prince sitting silently at his side, Durrant described the campaign to back Hifter and asked for U.S. support for their mercenary effort, the former NSC official told The Intercept. The upside, Durrant told the official, was that the U.S. help would limit Hifter’s reliance on the Russians, who were also supporting him in the war. The official, who asked not to be named because he feared professional reprisals for being publicly associated with Prince, balked. “It wasn’t something I wanted to be involved in,” he said.

In a statement, Prince’s lawyer, Matthew Schwartz, categorically denied the findings of the U.N. report and said he had asked the body to retract it. “Mr. Prince had no involvement in any alleged military operation in Libya in 2019, or at any other time,” the statement said. “He did not provide weapons, personnel, or military equipment to anyone in Libya.” Schwartz declined to respond to detailed questions from The Intercept, including about whether Prince lobbied Trump administration officials to support Hifter.

An attorney for Durrant, Vince Gordon, declined to answer detailed questions from The Intercept, instead providing a link to a statement in which Durrant acknowledged having set up a company called Opus, but said his work has never “involved any military operations or armed conflict. … We don’t breach sanctions; we don’t deliver military services, we don’t carry guns, and we are not mercenaries.” Durrant added: “I remain friends with Erik Prince and have no business or financial relationship with him.”

Many questions about Project Opus remain unanswered, including who paid for the operation, which allegedly cost $80 million, according to the U.N. report. It is also unclear what happened to that money after the mission failed, and whether its architects had help from other governments such as the United Arab Emirates, which has long supported Hifter.

The U.N. is continuing its investigation, and the FBI has been asking questions about Prince’s involvement in the Jordanian deal and his connections to the Libyan conflict. (“The FBI cannot confirm the existence of an investigation into Mr. Prince,” a spokesperson told The Intercept.) If the U.N. Sanctions Committee approves the report’s findings, Prince would face a travel ban and have his bank accounts frozen. At least four countries have opened criminal probes into the alleged Libya plot as a result of the U.N. investigation, according to a Western official.

The purpose of the mercenary mission was to provide Hifter with a “maritime interdiction capability … but also the capability to identify and strike land targets, and terminate and/or kidnap high-value targets,” the U.N. report concluded. The report, authored by an independent group of investigators who monitor sanction violations, known as the Panel of Experts, includes a PowerPoint presentation that outlines detailed plans for the mission.

The PowerPoint describes a so-called termination team, a hit squad composed of foreign mercenaries who would jump out of the helicopters to chase and kill their targets; it appears to be modeled on the secretive, elite U.S. Joint Special Operations Command. The PowerPoint lists 10 individuals as assassination targets, including commanders aligned with the U.N.-backed Tripoli government as well as two EU citizens.

A RIGHT-WING POLITICAL DONOR whose sister, Betsy DeVos, served as Trump’s education secretary, Prince founded the private security company Blackwater. After the company’s contractors killed 17 Iraqis in Baghdad’s Nisour Square in 2007, Prince changed its name and ultimately sold it in 2010. He later moved to the UAE and helped build a presidential guard for the royal family before being pushed out amid negative media exposure and questions about missing money. He

established a small investment fund called Frontier Resource Group that was financed by his personal wealth and focused on natural resources in Africa. Simultaneously, he set up a Hong Kong-based logistics and security company, Frontier Services Group, whose largest investor is a powerful Chinese government-owned investment bank.

During the Obama administration, Prince tried and failed many times to intervene in Libya’s devastating civil war. “Erik Prince has been attempting to deploy a small-scale aviation and maritime private military capability into Libya since 2013,” the U.N. report states. “The scale, organization and systems proposed were all similar to those deployed on the private military operation Opus in eastern Libya.”

Prince’s relationship to Hifter dates back to at least 2015, according to the U.N. report. That year, the report notes, Prince supplied Hifter with a private jet. Over a three-week period in February 2015, Hifter flew the Frontier Services plane to Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE — the Sunni Arab coalition that supported his effort to take control of Libya. On the day Hifter returned from his tour, the eastern Libyan government nominated him as the leader of its military. Shortly afterward, Prince began offering plans to use a mercenary force in eastern Libya under the guise of stopping the flow of migrants to Europe. The plans went nowhere.

When Trump won the White House, Prince wasted no time in inserting himself into what would emerge as a new Middle Eastern coalition under a new president. In January 2017, he flew to the Seychelles to meet with Mohammed bin Zayed, the crown prince and de facto ruler of the United Arab Emirates, known widely as MBZ. The crown prince would become a key player in the Trump administration’s evolving plans for the region. While Prince’s Seychelles trip has been probed for possible connections to the Trump-Russia scandal, there were other motives at play.

On the trip, Prince pitched MBZ on his private military ideas to support the UAE’s wars in Somalia, Yemen, and Libya. “Prince was like a kid at Christmas about his meeting with MBZ,” according to notes from special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigators, who interviewed Prince during the Trump-Russia investigation. “He could only focus on the presents under the tree.” After his appearance at MBZ’s private summit, Prince had what was then a secret meeting with Kirill Dmitriev, the powerful head of Russia’s sovereign wealth fund. The meeting with Dmitriev was initially suspected to be a backchannel effort by Putin and Trump to lift U.S. sanctions on Russia. The investigators’ notes revealed that the subject was Prince’s mercenary ambitions in the Libyan conflict. When the secret summit was over, Prince tagged along with MBZ on his private jet back to the UAE. During the flight, Prince later told special counsel investigators, Prince discussed his “idea for using a modified crop duster as a counterinsurgency plane.”

Prince had made his way into the Trump White House’s inner circle, forging ties to the president’s son-in-law Jared Kushner as Kushner sought to reshape U.S. policy in the Middle East, according to three people with knowledge of their relationship. Prince acted as a “shadow adviser” to Kushner, according to a former senior U.S. intelligence official familiar with their relationship. “This is completely false,” wrote Jason Miller, a spokesperson for Kushner. “Mr. Prince in no way served as an advisor to Mr. Kushner in any capacity.”

At the same time, Prince was acting as an unofficial adviser to MBZ. A leading buyer of U.S. arms, the UAE regained its position as one of America’s closest allies during the Trump years, following a chill in relations under President Barack Obama, and expanded its influence and military involvement in the Gulf and Africa. Within a year of Trump taking office, the Gulf nation had taken the lead in supporting Hifter as the figure most likely to defeat the U.N.-recognized government in Libya and perhaps unify the fractured country. The UAE ramped up its support for Hifter and his forces, providing air defenses, drones, and jets, as well as paying for foreign mercenaries to fight alongside Hifter’s troops.

“Kushner and MBZ decided to let Erik have some contracts while they reordered the Gulf.”

Prince benefited from the warm relationship between Kushner and the UAE, a former senior U.S. intelligence officer who consults with Middle Eastern governments told The Intercept. The UAE, the former official said, wanted the Trump administration to let it help Hifter win control of Libya, while the UAE worked to realize Trump and Kushner’s vision of a realigned Middle East. The Abraham Accords, which the Trump administration touted as its signature foreign policy achievement, involved normalizing relations between Israel and a handful of Arab nations, including the UAE. “Kushner and MBZ decided to let Erik have some contracts while they reordered the Gulf,” the former intelligence officer told The Intercept.

“Mr. Kushner has no knowledge of Mr. Prince’s contracts,” Kushner’s spokesperson told The Intercept. “Mr. Kushner has not even spoken or communicated with Mr. Prince since 2017, and any assertion otherwise is complete nonsense.”

AFTER LIBYA’S ARAB SPRING uprising shook the government of Col. Muammar Gaddafi, the U.S. and NATO allies helped overthrow him in 2011. The following three years, the country was largely stable, though political and geographic fissures and rivalries percolated. But when violent conflict between the U.N.-recognized Government of National Accord based in Tripoli and Hifter’s Libyan National Army in the country’s east broke out in 2014, thousands of civilians were killed and many more displaced. At least five countries began to provide military support to the warring parties, in violation of the U.N. arms embargo. Turkey has supported the GNA, while the UAE, Egypt, Russia, and Jordan have supported Hifter and the LNA. Thousands of foreign mercenaries flooded the country, and the war became one of the world’s most intractable conflicts.

Since civil war broke out in Libya, the U.S. has largely remained on the sidelines. Official U.S. policy has been to support the U.N.-led peace process, although Trump called Hifter in April 2019, after Hifter’s attack on Tripoli, to thank him for his counterterrorism efforts, according to news accounts at the time. The UAE has backed Hifter because it wants to quash any remnants of popular uprising and return the country to military dictatorship.

The political landscape created by Trump’s victory presented new opportunities for Prince to resume his push to support Hifter. The U.N. report, citing a confidential source, described an April 2019 meeting between Prince and Hifter in Cairo to discuss a planned mercenary intervention in Libya. In a statement, Prince’s lawyer said his client “has never met or spoken to Mr. Hiftar. This alleged meeting is fiction and never took place.” But two people with knowledge of Prince’s relationship with the Libyan commander confirmed to The Intercept that Prince does indeed know Hifter, and asserted that he has met with the Libyan strongman, along with one of Hifter’s sons. (In April 2019, the same month as the alleged meeting in Cairo with Hifter, the House Intelligence Committee formally sent the Justice Department a criminal referral on Prince, accusing him of making “materially false statements” to Congress in the Trump-Russia probe. Among the allegations made by the Intelligence Committee was that Prince tried to conceal from Congress the second meeting he had with Dmitriev in Seychelles about Libya.)

Project Opus was designed to leverage Prince’s connections to help Hifter gain the upper hand in Libya. The elaborate plan involved buying at least nine disused, U.S.-made military aircraft from the government of Jordan and airlifting them to the Libyan battlefield in June 2019. But there was an urgent problem: Jordanian officials were holding up the $80 million arms deal, which would have violated U.N. sanctions and possibly U.S. law.

Project Opus was designed to leverage Prince’s connections to help Hifter gain the upper hand in Libya.

On paper, the plan provided Hifter with a special operations force that could fly and kill at night in a bid to help the Libyan commander topple the GNA in Tripoli. Failing that, the paramilitary force could help Hifter resuscitate his military operation, which had stalled on the outskirts of the capital.

But Jordan’s leader, King Abdullah II, has ultimate authority to approve any deal for weapons from his small Middle Eastern nation. Prince knew the king well from the “war on terror” years, when Blackwater, Prince’s private security company, worked closely with the Jordanian government. Prince knew how Jordan’s levers of power worked and who could move them, so he contacted one of Abdullah’s personal advisers.

Prince asked the adviser to help an associate of Prince’s with what he described as a shipment of humanitarian aid. Abdullah knew about the shipment, Prince told the adviser, and it had been “cleared in Washington.” The adviser was troubled by Prince’s vagueness. “I didn’t know Prince as a humanitarian,” he later told The Intercept. Nonetheless, Prince told the king’s adviser that the associate would contact him.

Moments later, the adviser received a message on Signal from Durrant, a former Australian military pilot who had a long association with Prince. Durrant was using the screen name Gene Rynack, an alias that the U.N. report noted may have been a reference to Mel Gibson’s character in the film “Air America.”

Durrant, in the statement his lawyer provided, does not deny that he contacted Jordanian officials. But he portrayed Opus as a project aimed at supporting private companies and NGOs in war-torn Libya. “Through OPUS we provided engineering inspections and recommendations on the viability and value of several different aircraft. We were not involved in the sale of these aircraft beyond the inspection and viability recommendations,” Durrant asserted. “I was in Jordan as part of this project and held meetings with numerous Government officials.” But the texts Durrant sent the king’s adviser contradict those claims.

Those texts made it clear to the adviser that this was no humanitarian aid mission. Durrant asked Abdullah’s adviser to arrange for the Jordanian government to allow a scheduled first shipment of equipment and mercenaries to depart for Libya. Durrant briefly explained the situation: Nine U.S.-manufactured military helicopters, weapons, ammunition, and other equipment were headed to Libya, according to Durrant’s text messages, which were obtained by The Intercept. Durrant estimated that it would require 10 round-trip flights using a Jordanian military C-130 cargo plane to deliver everything, including the helicopters.

“We are paying J[ordan] for everything,” Durrant texted the adviser, including for the rental of the transport plane. Durrant then tried to coax the adviser to help by describing how beneficial the arms shipment would be for the kingdom. The Jordanians would “make money,” Durrant promised, “we are employing a lot of locals and #1” — a reference to the king, according to the adviser — “can take all the glory of [the] mission.”

Durrant then tried to reassure the king’s adviser, writing that “[r]eputation risk” had been assessed and promising, “we will hide/destroy any footprints.”

Durrant followed up with a phone call asking Abdullah’s adviser to keep the weapons deal secret, the adviser told The Intercept. Durrant said that although the Trump White House supported the mission and the CIA was aware of it, only Durrant and Prince knew all the details, according to the adviser.

The next day, Durrant sent a memo to the adviser outlining the status of the arms shipment as well as the planned military operation in Libya. Durrant called his group “Opus,” and the plan was as ambitious as it was unrealistic. Littered with military jargon, the memo, which was obtained by The Intercept and described in the U.N. report, listed the equipment and units headed to Benghazi. The helicopter gunships and weapons had been selected and inspected, the memo stated, and were ready to be packed up and sent across the Mediterranean into eastern Libya. The shipment would include surveillance airplanes that could be used to target people and enemy supply ships, as well as a drone. It also featured a unit to track and seize weapons smuggled via the Mediterranean by allies of the GNA, a cyber unit, and a medical evacuation plane. And it anticipated providing at least a dozen helicopters, including nine that Durrant intended to purchase from the Jordanian government. There would be a “marine strike group” with two armed boats that would be used to create a blockade, Durrant’s memo stated, forcing “enemy supply vessels” to dock in Benghazi, Hifter’s seat of power.

Now, with some of the shipment ready to move, Durrant and his team needed export licenses. “The team can be effective within 7 days if [the Jordanian government] supports with export of controlled items, including helicopters, air ammunition, ground weapons, ground ammunition and night vision,” according to the memo. Despite Durrant’s efforts and Prince’s outreach to the king’s adviser, the Jordanian military refused to sign off on the licenses.

IN JORDAN, Prince’s intervention in a “humanitarian” shipment was raising more questions for Abdullah’s adviser. If the king knew about the shipment, as Prince had told the adviser, and if the White House and the CIA were on board, as Durrant had claimed, why would Prince ask for help from one of the king’s personal aides?

Prince’s outreach and Durrant’s memo made several people around King Abdullah uneasy, and the Jordanian monarch signed off on a quiet inquiry to get to the bottom of it, according to the royal adviser and a second person familiar with the investigation. One of Abdullah’s military advisers, an active-duty British general named Alex Macintosh, was put in charge. Macintosh had formerly served with the British SAS, an elite commando unit, and the king respected his judgment.

Macintosh’s inquiry was brief, according to two people with knowledge of it. He met with Durrant, who was using a transparently fake alias and staying in an Amman hotel with what Macintosh later described as a motley-looking crew of Western mercenaries. Durrant told him he was buying nine helicopters from the Jordanian government — six MD530 Little Birds and three AH-1 Cobras — plus heavy weapons and ammunition. But Durrant didn’t have so-called end user certificates: internationally recognized paperwork that identifies where, to whom, and for what purpose arms are being transferred. This was the heart of the problem. With a U.N. arms embargo banning weapons shipments to Libya, it could not be listed as the destination for Durrant’s shipment. And because the aircraft were U.S.-made, their purchase would require preauthorization from the U.S. government, which had not been provided. The British general asked Durrant which country the end user certificates would list as the destination for the shipment. Durrant told Macintosh that they could declare the destination was Tunisia, Libya’s neighbor, or “anywhere else you find acceptable,” according to a Western official who discussed it with Macintosh. Macintosh declined to comment.

As Macintosh investigated, he made another discovery: The king’s brother, Prince Feisal Hussein, had been involved in the attempt to sell the Jordanian aircraft and arms, according to the Jordanian royal adviser, who discussed the finding with Macintosh. Feisal’s role was confirmed by two other people with knowledge of the deal.

In a response provided by the Jordanian Embassy, Feisal said he had no involvement in the attempted weapons shipment nor any relationship with Prince. “The government will conduct a full, transparent investigation into all allegations related to this alleged operation,” according to the statement. “In relation to allegations that have recently appeared in press reports, we confirm that Jordan sold no planes to Libya.”

The weapons sale had a certain logic. The Jordanian military had a stockpile of old U.S.-made attack helicopters donated more than a decade earlier by the U.S. and Israel to help bolster Jordan’s counterterrorism forces. But the helicopters were old and expensive to maintain, and Jordan ultimately had little use for them. Blackwater and Prince might have benefited most from the donated helicopters: Jordan’s military had hired the company in 2006 to train Jordanian special operations forces on how to use them. In Feisal’s capacity as a senior air force officer, he had worked with Prince and Blackwater on their training.

The king was told that Prince and Feisal were involved in the proposed weapons shipment, according to his adviser. By then, the CIA had learned that Prince and Durrant were claiming that the U.S. government had signed off on the deal. The CIA sent a message to Abdullah making clear the agency wanted him to stop the transfer, according to two people familiar with the CIA’s outreach, including a person with direct knowledge. The king agreed to shut it down. “You had Erik involved in a deal where [the Jordanian military] would have to issue fraudulent end-user certificates in an obvious violation of the U.N. arms embargo,” the adviser told The Intercept. “The king was advised that this could hurt future [legitimate] military sales.”

Despite Project Opus’s failure to get the helicopters and arms from Jordan to Libya, the mission to deliver a mercenary force to Hifter went forward. The mercenaries, led by a South African helicopter pilot, flew to Benghazi on June 25 or 26, according to the U.N. report and a person familiar with the operation. Durrant quickly purchased six replacement helicopters from South Africa for roughly $18 million and shipped them to Libya, according to the U.N. report. But the helicopters were old and unarmed, unlike the ones the contract had promised.

When Hifter learned that the Jordanian deal had failed and Durrant and his team had instead shipped six substandard helicopters, he flew into a rage and threatened the mercenaries, according to the U.N. report. Hifter sent the pilots back to their safe house under guard, according to a person with knowledge of the operation.

The mercenaries, concerned for their own safety given Hifter’s anger, decided to flee the country, according to the person with knowledge of the operation. On June 29, 2019, the team abandoned the six South African helicopters and escaped from a Benghazi harbor. They left for Malta on the same two rigid hull boats that Durrant had outlined in his memo, according to the U.N. report. The boats were supplied by another Prince business partner, a Maltese arms dealer. The trip took 36 hours after one of the two boats malfunctioned and had to be left behind. When they reached Malta, the mercenaries paid a fine for arriving without an entry visa and were released. Local media reported that they claimed to be civilian contractors who had fled Libya because the security situation on the ground was untenable.

Durrant claimed that the men were not mercenaries, instead portraying them as unarmed logistical personnel being sent in to support oil and gas companies. In the statement provided by his lawyer, Durrant claimed the men had entered the country “to setup a logistics centre in Libya. Within 48 hours they left due to security concerns. … Nothing happened and in no way were any sanctions breached.” Durrant denounced what he called the “politicization of the UN” through its investigation, claiming the investigators chose to use their “limited resources to pursue 20 unarmed personnel entering Libya for a 48 hour period yet thousands of armed mercenaries and seemingly limitless weapons are continually flowing into the country,” according to his statement.

Even after the Jordanian shipment failed to materialize and the mercenaries fled Libya, Prince and Durrant didn’t give up. Instead, they shifted their efforts to Washington. It was no secret that Prince advocated using mercenaries to support Hifter. From the early days of the Trump administration, he had pushed for a U.S.-backed, Gulf-funded private military force to enter Libya, according to Trump administration officials and documents. Before Hifter’s April 2019 offensive, Prince argued that his plan would end the ground war in Libya, stop terrorism, and make it easier to stabilize the country, according to a former Trump administration NSC official. “That’s just not something the U.S. government can do,” the former official said. “It sounds attractive and sexy because it sounds clean and easy, but it’s actually not, and [it’s] not legal.”

After the operation fell apart in June, Durrant continued to lobby members of the administration to revive the mission. One of those officials was Victoria Coates, then-NSC senior director for the Middle East and North Africa and one of the few Trump administration officials who had met Hifter. Coates knew that Durrant was a business associate of Prince’s; Durrant called Coates and told her he was supporting Hifter and wanted Washington’s backing. “I never met with Christiaan Durrant,” Coates told The Intercept. “After one or two phone calls, he made me feel uncomfortable.” Coates said she asked the White House switchboard to block future calls from Durrant.

When Durrant’s direct outreach failed, Prince contacted his friend on the NSC, one of Coates’s colleagues, for the meeting at the Army and Navy Club, which also led nowhere. Prince then reached out to yet another Trump administration official. This time, Prince asked the official to help connect Durrant with the CIA. The official spoke to The Intercept on the condition that they not be identified because they were not authorized to speak to the press. Durrant told the official that he was part of a military group working in Libya that included Americans and wanted CIA support. “He said ‘We’re with Hifter, we might be getting pushed out, and the Russians are coming in to support him,’” the official recalled Durrant telling him. “He kept it vague, but the bottom line was he said he was with Hifter,” and that if the CIA didn’t help, Hifter would turn to Russian mercenaries to try to break the stalemate. When the official passed Durrant’s message on to a CIA contact, the agency responded that it didn’t want to speak with Durrant and asked the official not to have further contact with him.

“The bottom line was he said he was with Hifter,” and that if the CIA didn’t help, Hifter would turn to Russian mercenaries to try to break the stalemate.

Durrant’s efforts to sway the Trump administration in his favor may have gone even further. In September 2019, Federal Advocates, a Washington lobbying firm, filed a disclosure with Congress after being hired by one of Durrant’s companies, Opus Capital Assets, which is based in the UAE. The initial filing described Opus as a “geopolitical national security firm” and declared that Federal Advocates had been paid $60,000 to lobby the Trump administration “on geopolitical issues in Africa.” Subsequent filings described Opus as an “oil and gas logistics services” entity, and Federal Advocates described its lobbying efforts as “providing educational background to the Administration.” Kevin Talley, one of the lobbyists, declined to comment on Opus or the contract.

THE U.N.’S PANEL OF EXPERTS opened an investigation in the summer of 2019. Its findings represent something akin to a grand jury indictment. The panel’s report was submitted to the U.N. Sanctions Committee, which will decide whether or not to approve its findings and designate Prince, Durrant, and others named in the report as weapons smugglers.

Prince’s lawyer denounced the U.N. investigators, claiming they did not give Prince sufficient chance to respond to the report’s allegations. “Given the astounding inaccuracies and falsehoods as reported in the media, and the absolute lack of due process or right to reply, we have requested that the Panel retract its report immediately,” he wrote. The U.N. report described multiple efforts to reach Prince and request his participation in the investigations, and said he never responded.

The panel’s investigators contacted most of the 20 foreign mercenaries detained in Malta and were also met with silence. Durrant’s lawyer, Gordon, told U.N. investigators that he represented Opus and those who fled Libya. Like the lobbying documents filed by Federal Advocates, Gordon claimed that Opus was an oil and gas logistics company; Gordon said that company personnel went to Libya for a commercial job, only to flee when it became too dangerous. The U.N. report described the oil and gas contract as a cover story to hide their true mission.

Investigators were able to slowly piece together the alleged mercenary plot after an African intelligence service tipped them off to fake export documents used to ship some of the replacement helicopters that were sent to Libya, according to a Western official familiar with the investigation. The U.N. panel obtained a copy of an $85 million contract for Opus to conduct a geological survey of Jordan. The document was “counterfeited with the deliberate intent to disguise the true purpose” and led back to companies in which Prince had an ownership interest, according to the U.N. report. (Gordon, Durrant’s lawyer, told The Intercept that Prince had no relationship with Opus.)

The contract was based on a real proposal from a geological survey company, Bridgeporth, whose logo adorns the bottom of each page of the document. In June 2019, when Project Opus was underway, Prince owned a significant share of Bridgeporth through his investment fund, FRG, which helped obscure Prince’s connection.“This is indicative of the complex multi-shells that Erik Dean Prince uses to disguise his control over, and benefits from, trading companies,” the U.N. report noted. After the U.N. inquired about the company’s possible role in the Libya operation, Prince changed his fund’s arrangement with Bridgeporth, making his continued investment less visible.

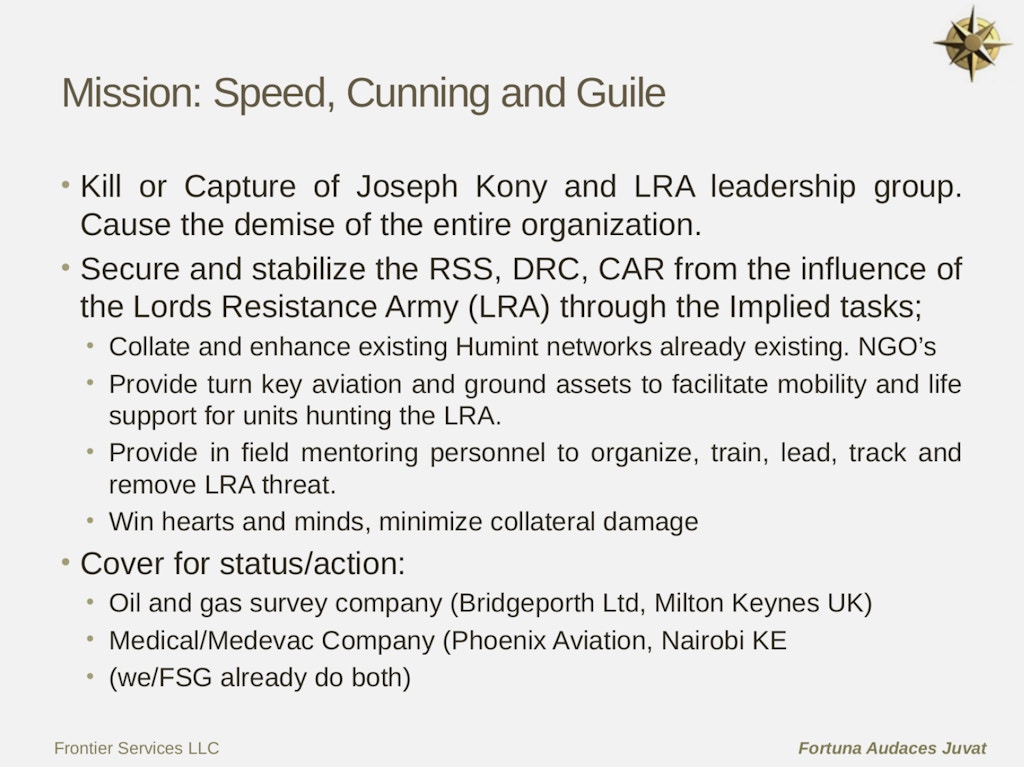

Prince’s ownership of Bridgeporth was another clue for the U.N. panel. It was not the first time Bridgeporth had been implicated in mercenary force proposals. In 2014, Prince created an assassination plan for Joseph Kony and the Lord’s Resistence Army in central Africa. The document, which was obtained by The Intercept, proposed using Bridgeporth and an oil and gas survey as the “cover” in the “kill or capture” mission.

One of Erik Prince’s early mercenary proposals was for an assassination operation in Africa. The plan called for using Bridgeporth, an oil and gas survey company Prince owned, as the “cover” for a “kill or capture” mission.

Image: Obtained by The Intercept

U.N. investigators traced three aircraft that made their way to the Middle East in preparation for the operation in Libya. The planes, all three of which were owned or controlled by Prince, were hastily sold to Durrant within days of their intended arrival in Benghazi. The U.N. report found that only Prince “was in the position to approve the sale and/or transfer of all three aircraft to support the operation in such a short time frame,” adding: “One quick transfer could be explained, but not three from different companies, all under the effective control or influence of one individual.”

The Intercept has previously reported on Prince’s drive to weaponize crop duster planes. The scheme involved two prototypes, manufactured by a U.S. company, and secretly modified into paramilitary aircraft. Prince and his partners utilized a front company, called LASA, to help market the converted crop dusters; the name stood for Light Attack Surveillance Aircraft. It was the very type of modified crop duster Prince was discussing with MBZ on his private plane after the 2017 Seychelles meetings.

The U.N. investigation discovered that one of the two LASA T-Birds had been flown to Amman in June 2019 in preparation for the Hifter operation. It was one of two planes that never made it to Libya, after being grounded in Jordan.

The assassination unit PowerPoint that the U.N. obtained depicts Jordanian helicopters of the make that Opus wanted to provide to Hifter alongside an odd-looking airplane. It is shown in various illustrations flying over a map of northern Libya: gathering digital signals, supporting the assassination and strike teams, hunting some enemy — real or imagined. The document lists the aircraft as the “LASA T-Bird.” There are only two such planes in the world, both created by Prince.

Matthew Cole has covered national security since 2005 for U.S. television networks and print outlets. He has reported extensively on the CIA’s post-9/11 transformation, including identifying and locating a secret CIA prison in Lithuania used to interrogate Al Qaeda detainees. Since 2005, Cole has traveled extensively in Afghanistan and Pakistan to cover conflict and investigate U.S. intelligence operations.For six years, Cole worked as an investigative producer for ABC and NBC News.

To see some of the memos and text messages mentioned in this article, go to Erik Prince and the Failed Plot to Arm a Warlord in Libya (theintercept.com) TF was not able to copy some of the memos provided in the original article.