Members of the Burlington (VT)-Puerto Cabezas Sister City Program (established in 1984 by then-Mayor Bernie Sanders and the Burlington City Council) are putting out an urgent call for help. Dan Higgins, a professional photographer who has documented the lives and livelihoods of the people of “Port” over two decades, is heading up the campaign., “A lot of communities lost their roofs,” he told Toward Freedom. “Houses are wrecked. It’s a major disaster.” Roughly 2,000 homes were destroyed.

Another 9,000 properties were partially damaged. “The Nicaraguan government is providing homeowners with sheets of zinc for their roofs,” Higgins said, “but the problem is there is not enough to go around to cover most people’s houses.”

Before the two Category 4 hurricanes slammed into this coastal community two weeks apart (Eta on November 4, Iota on November 17), authorities mounted intense efforts to get people out of harm’s way. “They did an excellent job,” Higgins said.“They got divers and fishermen safely on land and transported villagers away from the storm.”

But the damage to buildings and infrastructure is major, especially in the outlying indigenous Miskito communities where destruction of houses in some cases was total.

The people are now destitute and hungry. “Fishermen have been particularly hurt,” he said,” They lost their means of making a living, and people’s food supply has been impacted by crops having been destroyed.”

According to a report by the Alliance for Global Justice, some seventy thousand people were evacuated from the danger zone, “but two devastating hurricanes within two weeks would tax the resources of the wealthy nations, much less Nicaragua, the second poorest country in the hemisphere.” According to President Daniel Ortega, “Almost the entire country is in a national emergency, because it has been one hurricane after another, and this impacts all of Central America.”

Higgins has set up a Gofundme campaign to raise money for the people of Puerto Cabezas. A video showing the extent of the damage is posted within the link

Burlington’s Channel 5 (NBC) also did a story on the cultural and economic exchanges brought about over the years by the Sister City program.‘ Let them know we remember’: BTV sister city ravaged by hurricanes (mynbc5.com)

But there is more to the story of Puerto Cabezas. A centuries-old history of foreign intervention and plunder helps explain some of the cultural and political tensions that exist to this day between the costenos, as the coastal people call themselves, and the government in Managua located across a dividing mountain range that separates the Atlantic coast and the people of Puerto Cabezas from the Pacific coast.

Adjusting Expectations: A Deeper Look at Puerto Cabezas

To offer a better understanding of the region and the Sister City Program, members produced a video that commemorates their 25th anniversary. It features footage of their giant shipments of food and medical relief in the 1980s to a community torn by war, and decades later, their $11,000 worth of aid in 2007 when Hurricane Felix ravaged the coast with 160 mph winds. But the video goes beyond relief efforts and cultural exchange programs and provides a history of the Atlantic Coast that helps explain how many of its citizens got involved in Ronald’s Reagan’s “contra war”against the leftist Sandinista government. Through interviews with three of Burlington mayors and sister city members in Burlington and Puerto Cabezas (now called Bilwi), we get an appreciation of how and why they got involved, and how the Vermonters, all confirmed Sandinista supporters, adjusted their expectations once they found that there was strong pro-American, anti-Managua sentiment along the coast, as some indigenous communities resented the Ortega government’s efforts to introduce development programs that they felt violated their right to self determination. This continues to be an issue of intense controversy, which is why this video is useful in clarifying some misconceptions.

When the Sister City program first got off the ground in 1984, President Reagan’s illegal “contra war” against the Sandinistas was in full force. The war was highly unpopular in the US, which is why we see a shirt-sleeved, curly-haired Mayor Bernie Sanders enthusiastically announcing the program to throngs of supporters gathered outside Burlington’s City Hall. He goes on to extol the “extreme importance of the Sister City relationship in a time of war,” and declares that ”through visits to Nicaragua, and welcoming Nicaraguans here, through contributions of medicine, educational materials and agricultural materials, we will be able to stand up for peace and the needs of the people rather than war.” The crowd erupts in applause.

The video shows scenes of protesters marching through downtown Burlington carrying signs “No Vietnam in Central America.” Marvin Fishman, a member of the committee who visited Nicaragua several times, remembers those early days. “I was excited by the Sandinista revolution,” he explained. “To have a major change in government and ideology — from autocratic tin pot dictators like the Somozas to a Sandinistas revolution which had a people’s emphasis,which looked to revolutionize the country in a way I thought would be good — that was exciting.”

But the first wave of Vermonters who traveled to Puerto Cabezas discovered that it was not quite what they anticipated. This writer was among those who visited Puerto Cabezas in 1986, and would write upon return, “We learned that the Atlantic Coast was very different than Managua, that not all Nicaraguans were ‘Sandinista identified’ that some in Puerto Cabezas, like Oscar Palmer, longed for the ‘good old days’ of US influence in the region”. (It bears noting that part of the CIA’s Bay of Pigs failed invasion of Cuba in 1961 was launched from Puerto Cabezas.)

Explains Dan Higgins, “Whatever preconceptions we had about Nicaragua , we were to discover how little we knew about the Atlantic Coast. It is a region whose peoples, languages, culture and history are very different from the Spanish speaking side of Nicaragua.”

Historical roots to Nicaragua’s Contra War

The video, with accompanying maps, narrates the history of tensions between the indigenous communities on the Atlantic Coast, who were influenced by 17th century English traders and, in the 1840s, by the arrival of Protestant missionaries, as opposed to Spanish colonizers on the Pacific side of Nicaragua.

It was not until 1894 that the Nicaraguan government in Managua sent a military expedition to the Atlantic Coast –under one General Cabezas—to occupy and reincorporate it into the nation of Nicaragua. Needless to say, military occupation did not sit well with the indigenous peoples of the Coast. Decades later, in the early 1920s, a consortium of US lumber companies, mining companies, and Standard Fruit exploited the region and built up Puerto Cabezas as a company town. They eventually drained the region of its resources and departed, but left behind an enduring cultural impact: a love of American country music.

During the 1980s, members of the Miskito, Sumo, Rama and Creole indigenous communities struggled to have their own autonomous regions and resisted Sandinista efforts to introduce development programs into the region. Some joined the Contra counter-revolutionary militias which were supported by the US in an effort to overthrow the Sandinistas. As Mayor Peter Clavelle explains,: “We supported the Sandinistas, but lo and behold, we found ourselves in a Contra stronghold. So how do you deal with that? One way was to forget the politics and provide humanitarian aid.” The people of Burlington proceeded to raise money and gather material aid amounting to 30 tons of medical supplies (including an x-ray machine), food, blankets and clothing, for shipment to their sister city. The Burlingtonians reached out to other humanitarian organizations to join in their material aid program. The response was extraordinary. “We adopted our own foreign policy,” Clavelle recalls, “guided by people to people contact.” Cultural and economic exchanges ensued: a baseball team came to Burlington, as well as a dance troupe; Burlingtonians taught video filmmaking to the people of Port; Charlie Delaney, an Abenaki from Vermont and carpenter, helped add an addition to a home in Port using local materials and employing local workers at decent wages.

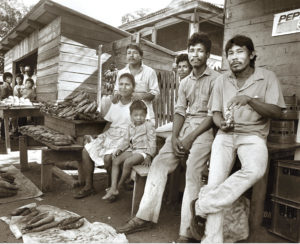

Meanwhile, Dan Higgins sought to record the many faces of Puerto Cabezas, since “the images in media showed us only pictures of the war.” In 1986, he made his first trip to Nicaragua to photograph portraits of the people “in the most ordinary situations in the social life of the town.” His plan was to a pair them up with people in the same social situation in Burlington, “so residents in each community would better understand each other. Where do you go to school? Where do you get a haircut? What does your church look like?”

You can see a marvelous 2017 exhibit of Higgins’ many photos over the years here.

In 1987, with the Contra war winding down, a new Nicaraguan constitution was ratified as well as Law 28 that divides the Atlantic coast into two autonomous regions. As Higgins explains, “It gives, at least on paper, some local control over indigenous territories.” Higgins adds, on a sober note, that “the issue of autonomy continues to be a flash point in Nicaraguan politics, with differing interpretations of what autonomy means.” Even now, indigenous lawyers representing Bilwi residents have brought legal challenges against the government, alleging it has failed to enforce the autonomy law. Of particular contention is whether the government took adequate steps to prevent colonos (settlers) from moving onto indigenous lands, and more recently, whether it has removed them, an issue which some indigenous defenders of the government argue is complex but gradually being resolved.

The video, for its part, ends on a positive note: the marriage of Vermonter Mary Brook with Elvis Finley, a Miskito Indian from Bilwi. They have been married for 12 years and have two young children. A closing scene shows a Bilwi citizen saluting his sister city in Burlington. “Every time you visit us, we feel good. You make us feel alive again, you make us feel good.”

As of last week donations have started to pour in to the Sister City Gofundme campaign. Contributions can also be mailed to: Burlington-Puerto Cabezas Sister City Program, 15 Beech St., Burlington, Vermont.

Charlotte Dennett is the Guest Editor of Towardfreedom.com. She is the co-author with Gerard Colby of Thy Will be Done. The Conquest of the Amazon: Nelson Rockefeller and Evangelism in the Age of Oil . Her new book is The Crash of Flight 3804: A Lost Spy, A Daughter’s Quest, and the Deadly Politics of the Great Game for Oil.